Review by Ian Keogh

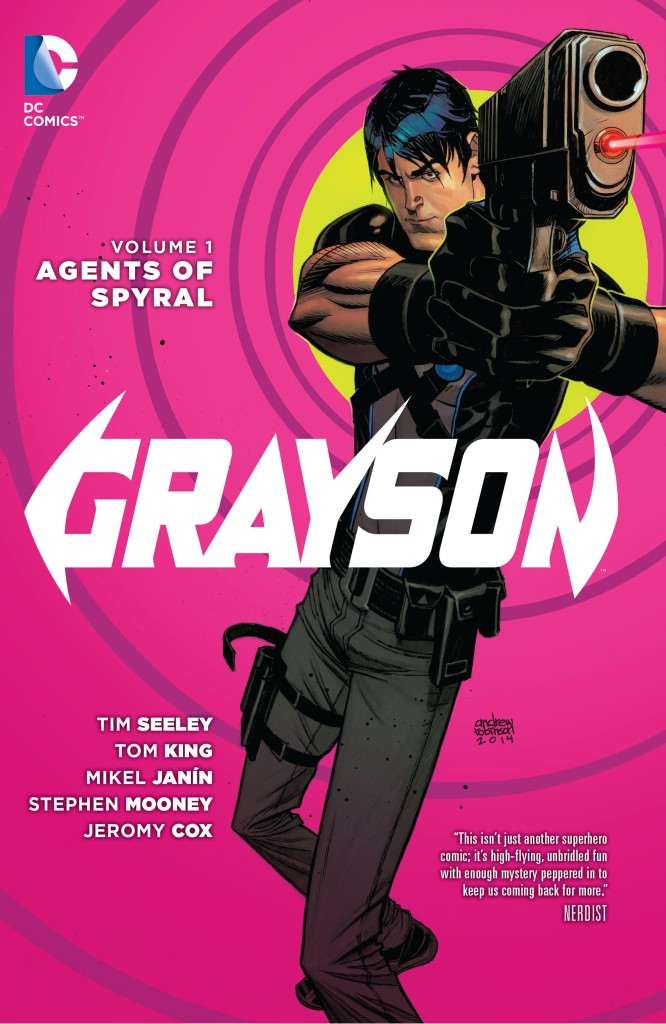

At times it’s seemed that DC’s not known what to do with Dick Grayson. Introduced as Robin back in the 1940s, he was Batman’s way of explaining the plot to readers, but his progression to Nightwing forty years later begat an enormous following that was often not understood. This was sustained throughout his flying the Gotham coop, and becoming what was to all intents and purposes the Batman of Bludhaven. He’s returned to substitute for Batman, and gradually it dawned on DC editorial that for many Dick Grayson is a sex symbol. Agent of Spyral emphasises this at every possible opportunity, and Dick even gets to enjoy a sex life.

It’s amid a strange plot. Introduced by Grant Morrison in Batman Incorporated, Spyral is an agency once dedicated to killing anyone with super powers, but now following the less fatal path of cataloguing the secret identities of masked crimefighters, and neutralising threats. It thrives on misinformation, deceit and mind conditioning, and among the technology it employs is a device ensuring its agents, who don’t wear masks, can never have their facial features remembered or captured digitally. The hypocrisy isn’t commented on.

Spyral is a 1960s spy gadget wonderland, and artist Mikel Janín revels in it, filling the pages with improbable gadgets such as the walking chair used by the mysterious Mister Minos, and suitably deflective background patterns. His page layouts are exemplary in prioritising dynamism and excitement, and he has a style that’s easy on the eye.

Those unfamiliar with Midnighter and his current situation are rather left hanging with regard to his involvement as no concessions are granted, but from the halfway point there’s much to admire about Agents of Spyral. Tom King and Tim Seeley collaborate on the writing, plotting together and alternating with the scripts. There’s less expository dialogue in the chapters written by King. To begin with everything is delivered with a knowing wink, rarely in subtle fashion, but these are just teething problems, and the third chapter signifies a transformation, with a more human story even if the villain is ridiculous, and a joyful fourth chapter panders to the Dick Grayson audience.

The most impressive piece here is the final chapter set five years in the future. It begins with the end and ends with the beginning, yet within this ambition still tells a cohesive story and when reading to the end you know how the beginning will continue. Does all that make sense? It does when reading. Stephen Mooney’s not the artist that Janín is. His figures are stiff, and his anatomy occasionally off, but the pages display a good design sense, the storytelling is strong and he’s much better in the following We All Die at Dawn.