Review by Ian Keogh

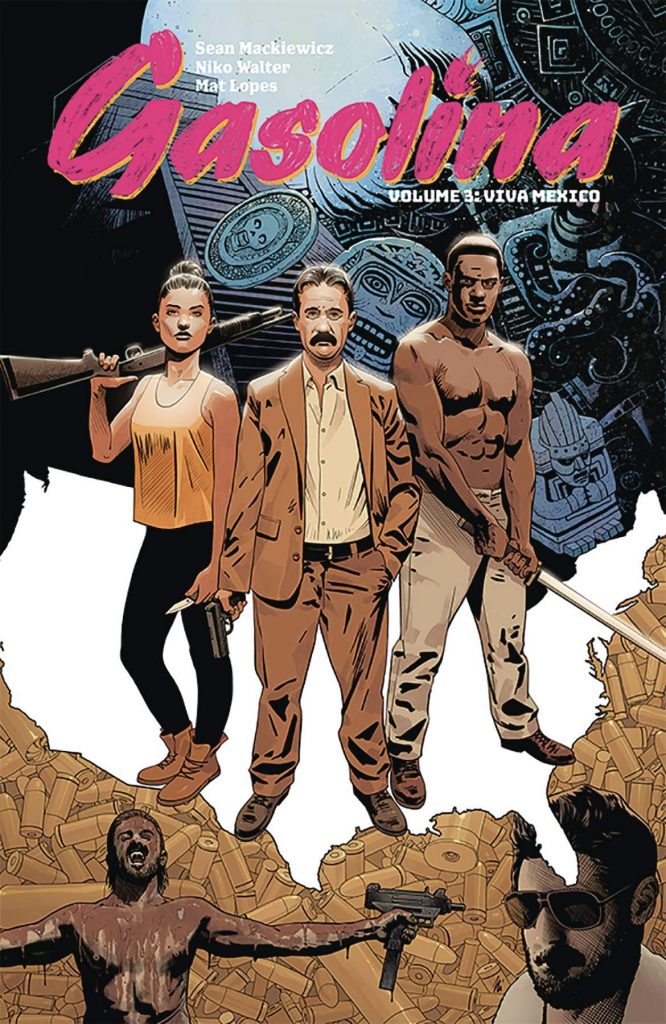

Viva Mexico concludes this three volume crime thriller with the horror overtones of Lovecraftian creatures welded to Latin American myths. Everything has been building to several confrontations, and they play out here. It’s prompted by a new cartel entering the Mexican drug wars, and Las Queridos are interested in more than just domination. They serve an ancient evil existing before humanity, and now revived.

Amalia and Randy have been at the heart of Gasolina over the previous two volumes, she Mexican and he an American, ending up near her family home outside Veracruz. We’ve known they can’t return North, and over the opening chapter Amalia reveals part of why that is. Sean Mackiewicz tells a horrific story, yet about a threat Mexicans crossing the American border face daily, and leaves us to join the dots. He doesn’t make much in the way of concessions, presuming that no-one’s going to begin reading Gasolina with the third volume. It’s a small mistake because there’s an ambitious range to the series, and it frequently jumps from the present to the past without any great indication that’s the case. Several characters not seen in Fiesta return here. With some just the context of their appearance provides understanding, but partitioning the chapters into groups of six means a long time since we’ve seen Arguello, and he’d have been better kept a little more in the foreground.

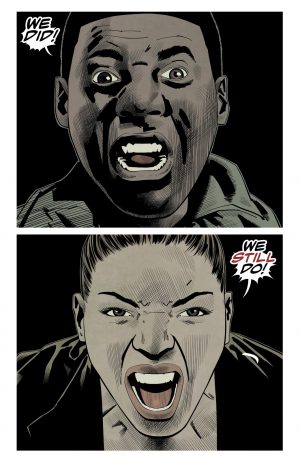

There’s still sometimes figures that are too static on Niko Walter’s pages, but his storytelling’s otherwise first rate, moving the viewpoints around, and having a good eye for a dramatic contrast, as seen on the sample page row between Amalia and Randy. Until now he’s ensured the horror hasn’t been explicit, but with the end approaching Walter shows he can draw the results as well as set the suspense. It’s grim stuff.

Gasolina holds it together until the final pages, when it seems Mackiewicz can’t work out exactly how to finish. He’s worked through the full Tarantino repertoire, and it’s been good, but the ending falls to pieces. Are we meant to see the entire evil as a metaphor for drugs? An even worse interpretation is as immigrants, but let’s presume that’s unintentional. Certainty and closure isn’t an essential ending, but in this case it would have been better than what we get. Still, most of Gasolina has been one hell of a thrill ride, and both Mackiewicz and Walter’s subsequent work should be even better.