Review by Graham Johnstone

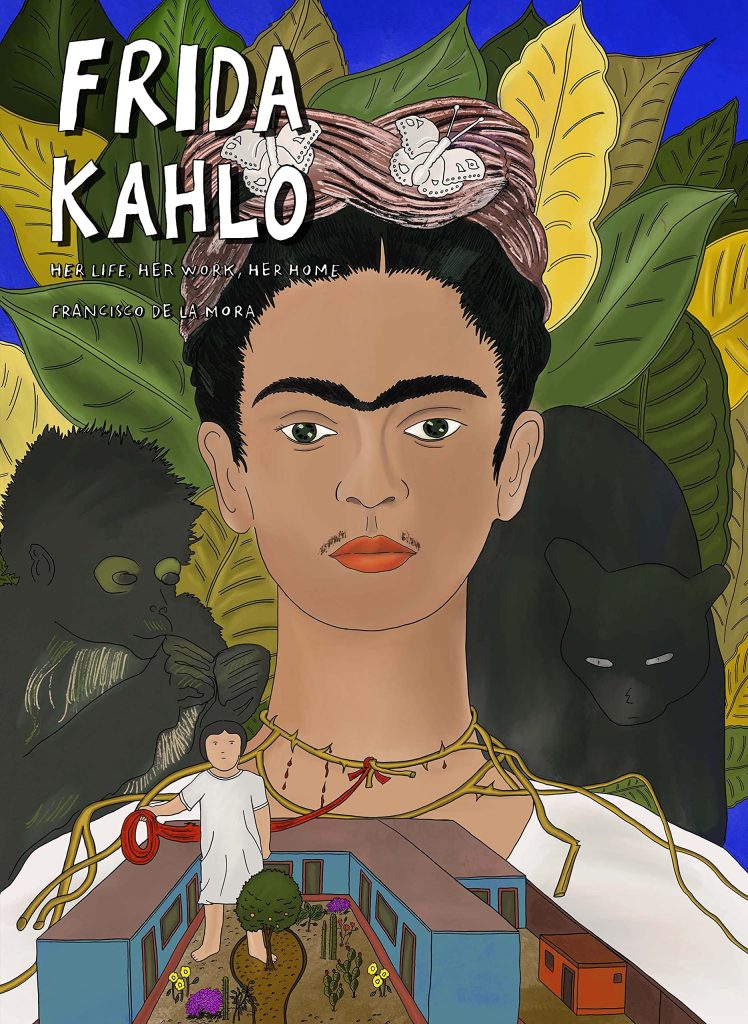

Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo is far more famous than during her lifetime (1907-1954). While European artists pursued an international modernism, Kahlo embraced the local: flora, fauna, traditional dress, and most iconic of all, her assertive monobrow. By the millennium, she was famous enough to inspire a Hollywood biopic. Her image, captured in photos and self-portraits, has been widely reproduced and recreated in postcards, fan art, and merchandise. However, it took until 2023 to front her graphic biography. Kahlo lived far from modern art epicentre Paris, suffered disability, and enjoyed sexual openness. In a genre (reflecting the art canon), dominated by Dead White Males, Kahlo adds welcome diversity.

Francisco de la Mora wrote the graphic biography of muralist, and fellow Mexican Diego Rivera, so he’s well placed to tell the story of Rivera’s brilliant wife. The earlier book was novelistic – unfolding the story in dramatised scenes, but here de la Mora’s approach is more documentary, relying heavily on narration. He quotes from Kahlo’s diary and other texts, giving authority to his account, but leaving questions as to whether other statements are quoted, paraphrased, or invented.

The subtitle promises “her life, her work, her home”. We see her home, even before her life begins, and it remains a constant, hosting visitors like Surrealist agitator André Breton, and exiled Soviet leader Trotsky. Key events are childhood in the throes of the Mexican Revolution, the accident that crippled her, and her ‘second great accident’- Rivera. Accounts of her deteriorating health, and upbeat spirit, are moving, while other moments are amusing, often mischievous. Breton involves her in a Paris exhibition, and her response on return is to rail against the city, its bohemians and Surrealists, who “never stop talking,” and rarely work.

A page count hardly more than Frida’s 47 years, only adds up to a graphic novella, and by opting for birth-to-death coverage rather than, say, a-year-in-the-life, it’s inevitably compressed, favouring completeness over immersion. This means crucial events, like the life-changing road accident, fall surprisingly flat. Poignance would come from reader investment in Frida’s wanderlust, and feelings for her travelling companion, elements added here as hasty catch-up while they lug their cases to the fateful bus. It segues – between pages – from meeting Diego, to marrying him. Her request for “loyalty, but not fidelity” is revealing, but otherwise, there’s little insight into this all-important relationship. We hear of his affairs, but not hers, with women and men, including Trotsky – surely a bankable anecdote to enliven any book? Whether due to lack of space, lack of planning, or sanitising a martyr heroine, we lose a lot of Frida.

Despite the subtitle, Kahlo’s work gets less attention. There are interesting insights (“feminine qualities of resistance, truth, […] suffering”,) though typically pronounced in captions. Dramatising the creation of even one painting, from idea to completion, might have better demonstrated the stated qualities, and enriched the book.

Neither does the art match José Luis Pescador’s slick illustration on the Rivera book. De la Mora’s figures have, at best, a naive charm, though he’s a solid storyteller, with detailed settings and apt colour palettes adding appeal. He makes good use of large, well-composed panels, often overlaying other pictorial elements, or text in visual forms like hand-written letters, or flyers. The ailing Frida attending her exhibition launch in her bed, is a potent image that would have benefited from larger scale, highlighting missed opportunities, and some lack of care.

Frida Kahlo offers a fair overview of a fascinating life, but even within the limited page count, it could have offered more vivid details, greater insight into her work, and more poignant human drama.