Review by Frank Plowright

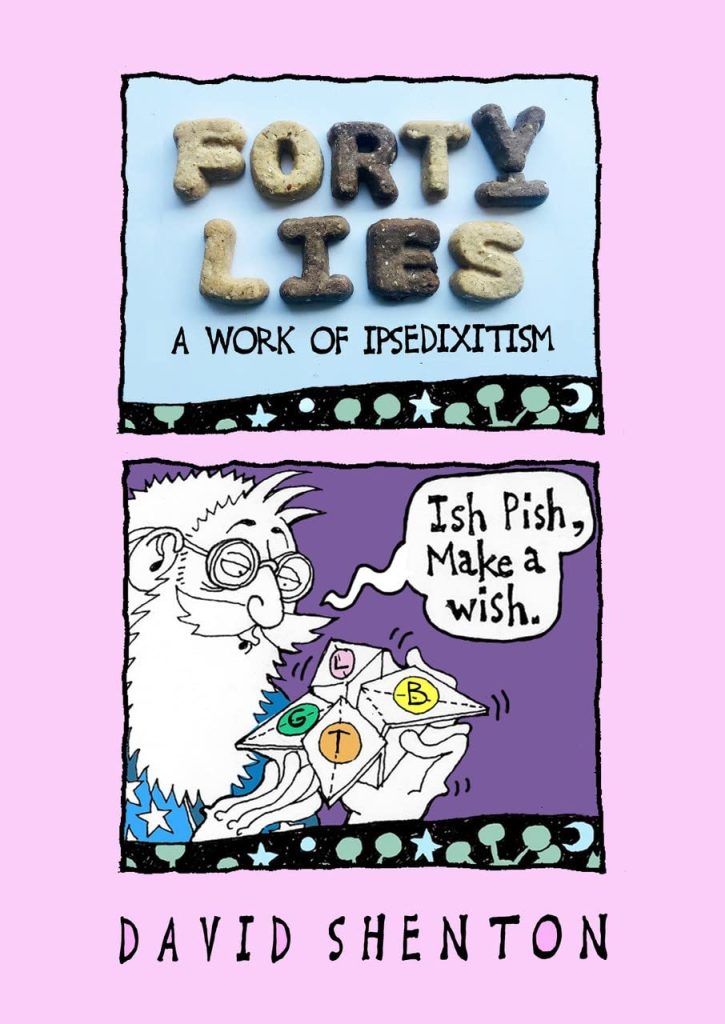

David Shenton’s had a very successful career as a cartoonist, but one largely restricted to London publications and gay magazines, which means he’s unknown to a significant percentage of those frequenting comic shops, even the more enlightened boutiques. His extensive and hilariously self-effacing conversational autobiography Forty Lies ought to parade his talents before a wider audience. At the very least it’s the first graphic novel to offer knitting patterns as bonus material. You’ll also find a board game on identifying your sexual orientation and dress-up figures, although making the most of them requires buying two copies (or use of a scanner and printer).

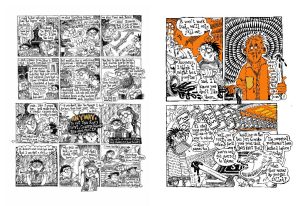

A reason for Shenton’s success is an ability to define people in an illustration, even if just required to deliver lines in gag strips. An editor once sacked him for only being able to draw old men with moustaches and checked shirts. They really weren’t looking. Early in Forty Lies he relates how he spent considerable time with his grandmother after her husband’s death, and the sample art provides her gloriously eccentric, yet utterly humane personality. She passed on a love for knitting and Shenton shows how his family and upbringing shaped much of who he was, although there’s strangely little genetic precedence shown for a sense of humour able to prise a joke from almost any situation.

His sexual orientation, though, developed naturally, and Shenton takes a tour through perilous times, his awakening occurring before British decriminalisation in 1967, and much about AIDS later. Shenton supplies the dangers and the persecution, but in what seems an anger-free manner, although the emotion is there, just suppressed by the humour, a gay meeting in Cromer in 1976 relating a litany of lives destroyed. It’s also one of Shenton’s clever rhyming sequences.

Once seen, Shenton’s art is instantly recognisable, packed to bursting with noodling or detail, the characters within straining for escape from the constricting panels. Colour is extremely effectively used, placed minimally for decorative effect or emphasis within otherwise black and white strips. There are plenty of these, as Shenton includes highlights from stages of his comic career, which are snapshots of the times, and still funny. Parts of Forty Lies are also produced scrapbook style, incorporating photographs, press cuttings and satirised, poorly conceived 1980s AIDS information leaflets.

Diversions are plentiful, informative and entertaining, as proved by a five page detailing of a trip to a Finnish comic convention that ends up in Russia, and numerous rib-ticklers about activism. Shenton also has comments to make about the barriers around gay culture, not least the terminology, and behavioural expectations shifting according to venue. This is all in anecdotal form, and almost the grumpiest Shenton actually becomes is during the hilarious recollection of the night he meets his husband. Actual anger only manifests during poor and judgemental health treatment.

Forty Lies is a raconteur’s delight. It’s like being sat around the fire in the country pub and gradually finding out about the people who’re snowed-in with you. You’re going to be there for a while, so you might as well make the best of it, and the discoveries are delightful.

Oh yes, cleverly, the title’s also an anagram.