Review by Ian Keogh

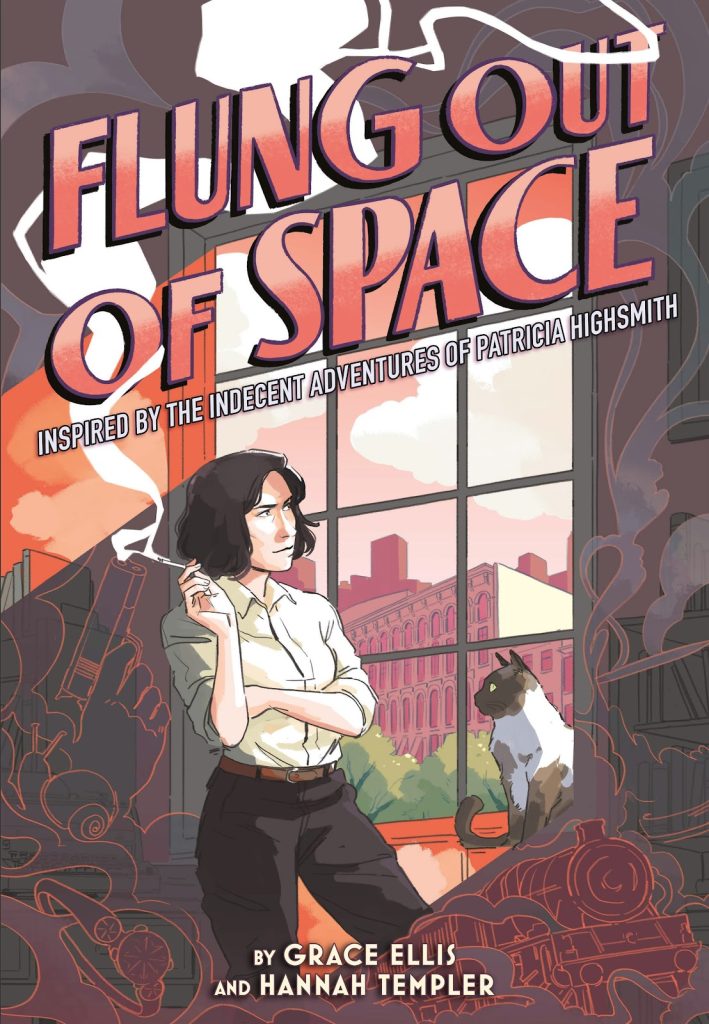

Before the career generated by her first novel Strangers on a Train in 1950, Patricia Highsmith wrote comics, which is where Grace Ellis picks her up for this biographical glimpse prior to acclaim, fame and success.

Highsmith has anxieties about being attracted to women in times when that was taboo, for which she’s seeing a therapist, and she’s especially disenchanted about writing comics, which she considers trash. A dissatisfaction with life manifests in an abrasive personality, yet until her agent can place her novel there’s no way out. Ellis delivers this feeling of being stuck in a rut, with the most effective scenes being the sparkling dialogue when she’s sparring with two different therapists.

Indeed, this is an understanding and sympathetic portrait for contrasting Highsmith’s caustic moments in public with her torment when alone. While much of the former can be verified to a degree, the latter is by solitary nature unknown. The way Ellis portrays Highsmith is as someone constantly pushing people away, building a wall layer by layer, yet how would someone behave if denied the possibility of being who they are? Part of what Highsmith hates about comics is the lack of reality, yet when she writes Carol (or The Price of Salt), about a lesbian couple, which is real to her, the response from publishers is almost universally negative accompanied by the suggestion of a pseudonym. That, though, is a contentious moment underling the fictionalising of experience, as rather than accepting a publisher’s proposal of a pseudonym, it was a decision she arrived at herself. Much later in life she’d say the initial reaction when submitted under her own name made her realise the possibility of typecasting as ‘the lesbian novelist’ were she to publish without an alias.

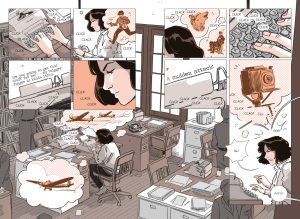

Further gloss is added by Hannah Templar’s simple and attractive art. She poses people effectively to bring out their personalities alongside their features, and defines the times via clothing and accessories. Everyday life is separated by an occasional flight of fantasy, and Templar supplies these as accomplished montages, including a contracted version of Carol over several pages.

There’s more than a suspicion that Ellis has toned down a famously offensive personality with objectionable views, considering mentioning it in the introduction enough. In the text it’s been reduced to a couple of anti-Semitic comments. Considering Ellis is literally putting words in Highsmith’s mouth via the dialogue in a form she despised, this can seem prioritising lack of offence in the present than being true to the woman she was.

That reservation aside, Flung Out of Space is a viable portrait of Highsmith and the depressing times when being gay was considered a treatable condition.