Review by Ian Keogh

According to an interview given to the Guardian newspaper to coincide with the UK publication of Esther’s Notebooks, it orginated when Riad Sattouf’s friends brought their nine year old daughter along when visiting. He enjoyed her chatting away about her life and school experiences without any shyness, and suggested producing a weekly strip bringing Esther’s thoughts to a wider audience. It’s been successful enough to have continued for six years and counting. Esther isn’t her real name, and presumably the names of everyone else in the strip have also been anonymised.

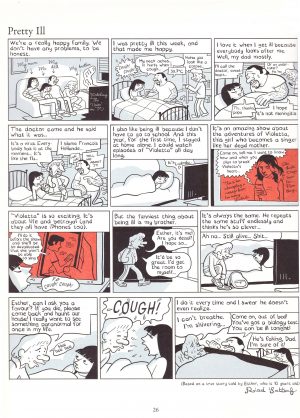

Sattouf’s perfect cartooning brings Esther’s home and school days to vivid life, designing her world with panache and precision, and applying equal consideration to drawing the characters, with the selection of gruesome boys especially good. Esther swithers between scathing condemnation at their stupidity, especially that of her older brother, and an attraction she doesn’t quite understand. She might not understand everything, but Sattouf passes on how observant she is, and how she picks up on things not being quite right.

There are numerous other aspects of life that pass above her head, some hilarious and others poignant. An early strip about the 2015 murders at satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo exemplifies this while also representing her innocence. Esther is unsure why a politician has turned up at her school and led a minute’s silence, during which she struggles not to giggle as the serious contemplation of her classmates amuses her. More important is her best friend Eugenie falling out with her, although as we later see, Esther’s hardly without guilt when it comes to her treatment of Eugenie.

Esther’s obsession is having an iPhone 6, and recurring mentions of this over numerous strips become a running joke. The one black mark racked up against her father, whom she otherwise adores unreservedly, is that he’s forbidden her having a phone until she’s at secondary school. Interestingly, her mother is rarely mentioned, and then only in terms that to adults may seem half-hearted. Perhaps that’s only in comparison with her father.

While most of the strips are lighthearted amusement, there’ll occasionally be a tragic event filtered through Esther’s perceptions, not just concerning the wider world, but her own life. Sattouf supplies this with same consideration he applies to Esther’s unknowingly funny comments, relating them naturally without emphasis, so never ridiculing Esther.

Esther’s Notebooks has an adult rating due to the amount of swearing, although to Esther’s ears it’s meaningless nonsense, and one delightful strip concerns her logically dismantling and flipping around the term “ho”. Esther seems a reasonable representation of her generation, although perhaps a little smarter than many, and so whether intentional or coincidence, Esther’s Notebooks also serves as social observation, which will come more sharply into focus as the series continues. This opening volume already shows distressing attitudes towards girls embedded at an early age, seemingly at a level beyond the ignorance of that age. It’s a secondary element, but concerning.

Otherwise Esther’s Notebooks drips with charm and insight, good humour provided to excess. It’s a rare strip missing at least one laugh out loud moment, and Sattouf skilfully steers Esther’s tales to punchlines. She ages a year over these 52 strips, and Tales From My Eleven-Year-Old Life is also available in English.