Review by Ian Keogh

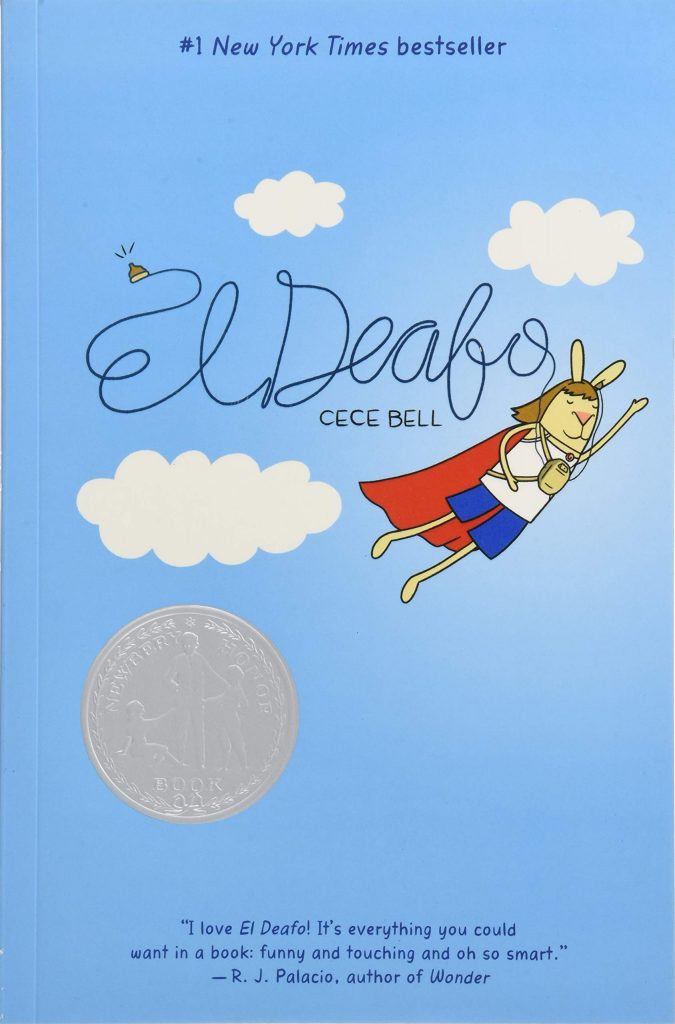

At the age of four Cece Bell contracted a form of meningitis that left her almost deaf, a condition she was unaware of at first, just thinking something strange had happened. This was the mid-1970s, and the technology available to help her then was a large device known as a phonic ear that strapped to her chest with an earpiece on a lead. If that were the entire story Bell might have run out of steam pretty rapidly, but it’s one aspect of a well remembered childhood during which there are other problems, beginning with a controlling best friend. This is Laura, self-assured, but at the cost of constantly reinforcing that by putting the young Cece down.

Despite emphasising hearing problems, these are just the way in to a wider exploration of what some children endure at primary school, as Cece’s a sensitive child with a long memory for what hurt deeply at the time. The title comes from the confidence-building fantasy identity the young Cece assumed after hearing a deaf character on a TV show being insulted. She uses El Deafo as an escape mechanism, as the superhero who can achieve what she couldn’t when mulling things over after events. It’s sometimes funny, sometimes heartbreaking, as is another constantly reinforced scenario. On discovering that Cece is deaf she constantly has to endure comments about her being special, and people raise their volume and slow their speech, which doesn’t necessarily help. This isn’t intended as patronising, but highlighting it in a book aimed at a younger audience is educational, and should inform. Cece acknowledges that she wasn’t the most co-operative in making life easier for herself, sign language being a point of contention, but underlining so much is what children go through and what sticks with them.

Has there been any testing done as to whether children respond more thoughtfully to a story if they know it’s autobiographical, or in this case largely autobiographical? While too good natured to qualify as a misery memoir, the first person captions constantly reinforce that it’s a real person experiencing hurtful behaviour, and the intention is educational. Children are capable of casual cruelty without being able to rationalise it as such, and a sugar coated pill highlighting this to them has to be worthwhile. To ensure the message seeps in as far as possible the illustrations have a child-like simplicity, a form children can copy. Bell has chosen to illustrate her younger self, and everyone else, with rabbit ears, a representation that appears to have no significance beyond whimsy.

For all the painful experiences, El Deafo has many joyful moments as it takes its course through junior school. Cece learning her radio hearing aid can pick up what her teacher says and does well beyond the classroom is a gleeful discovery, as is the later use of the technology. There’s also the awkwardness of first love and the pitfalls of the sleepover.

El Deafo should make any child think about their behaviour, and how it might affect others. While doing so they’ll be reading a thoroughly charming sugar coated pill.