Review by Karl Verhoven

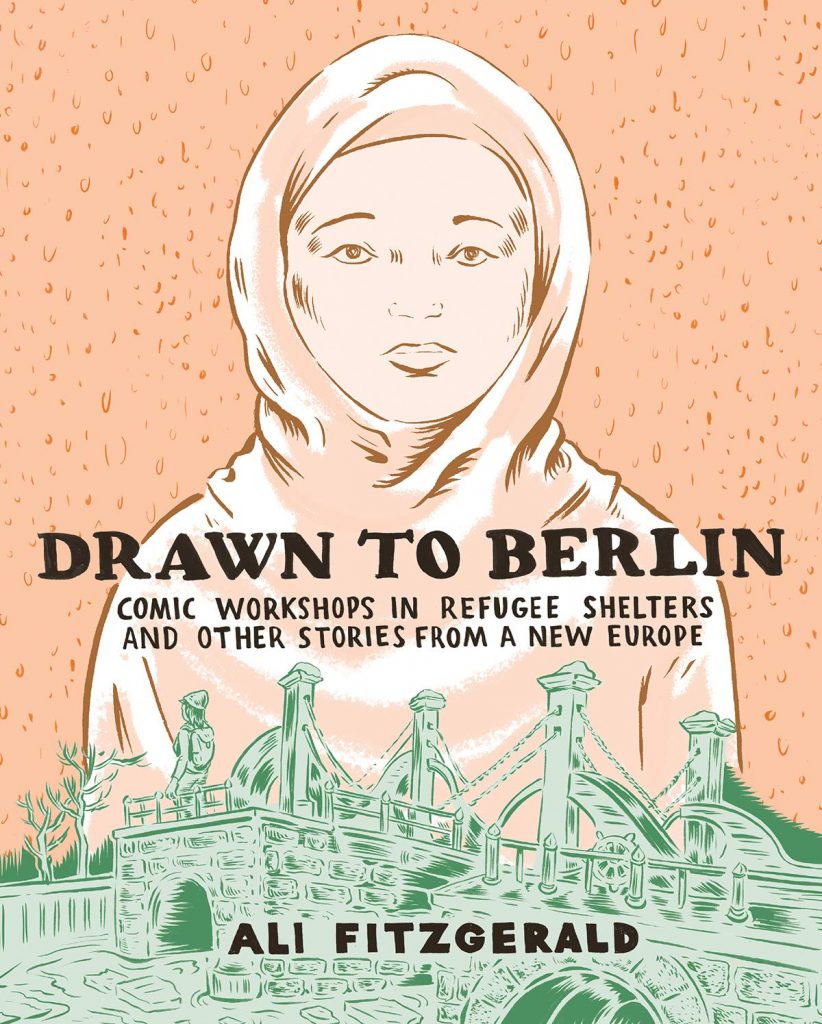

Drawn to Berlin is a memoir of Ali Fitzgerald’s time in Germany providing comic classes for refugees around 2016. “I sort of believe in the gospel of comics”, she tells us endearingly. To begin, despite the personal interpretation and interesting art-related observations, there’s a sense of the project being worthy without entirely captivating, but Fitzgerald ups the ante considerably by drawing comparisons with Berlin’s previous large influx of refugees around the turn of the 20th century. The present day people she’s interacting with are largely Syrian, whereas just over a hundred years previously large numbers of Jews arrived in Berlin, fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe.

The most obvious comparison is to the reportage of Joe Sacco, but a closer match is the work of Harvey Pekar. He had a similar manner of being able to see beneath the surface, intruded himself more into his work, and had a deep interest in history and how the past informs the present. The current refugees had a longer journey and administrative red tape blighted their lives, whereas the Jewish refugees were able to settle more easily, but had to make their own way with no support services. As her own narrative continues we learn Fitzgerald questioning the increasing influence of the right wing anti-refugee parties in Germany, their use of cartooning to vilify, and the increasing attacks on refugee shelters. She’s like an eye-opening tour guide, showing us her Berlin along with that of the refugees past and present, taking diversions into the associations of the Fraktur typeface or the recollections of Berlin in previous eras as filtered by Joseph Roth and Christopher Isherwood.

Many small observational moments are passed on as something to mull over. Why did most refugees leave their drawings behind unless they were portraits? We read the chilling phrase “she advocated, in soothing tones, the shooting of refugees crossing the border”, there’s speculation about what refugees were drawn to in certain graphic novels, and how children found it so easy to draw detailed guns. A riddle about a black dot is especially resonant.

There is considerable and deliberate repetition, used to reinforce repeated experiences, but a distancing element is that there’s plenty about current status, but only hints about what they’re fleeing from, why they’re refugees. This isn’t down to a lack of understanding. Fitzgerald tries to maintain an open mind, but multiple recollections of inhumane treatment in Hungary colour her attitude toward the entire nation. She doesn’t belabour the obvious, but the subtext is that it’s easy to slip into irrational prejudice. It’s also easy to apply amateur psychoanalysis to what people draw, and Fitzgerald doesn’t resist, but only occasionally has her speculations confirmed or denied.

Toward the end of Drawn to Berlin we’re presented with a quote from a play by Omar Abusaada retrofitting the Greek myth of Iphigenia to reflect the experiences of refugees in Germany: “In tragedy there is always a violent jump from an old world to a new world. We’re witnessing this right now.” It’s a resonant encapsulation of Fitzgerald’s entire point. It’s also impossible to come away from Drawn to Berlin without the power of art filtering through, both for good and bad, and in arguments about what should be financed this is all too often dismissed.