Review by Frank Plowright

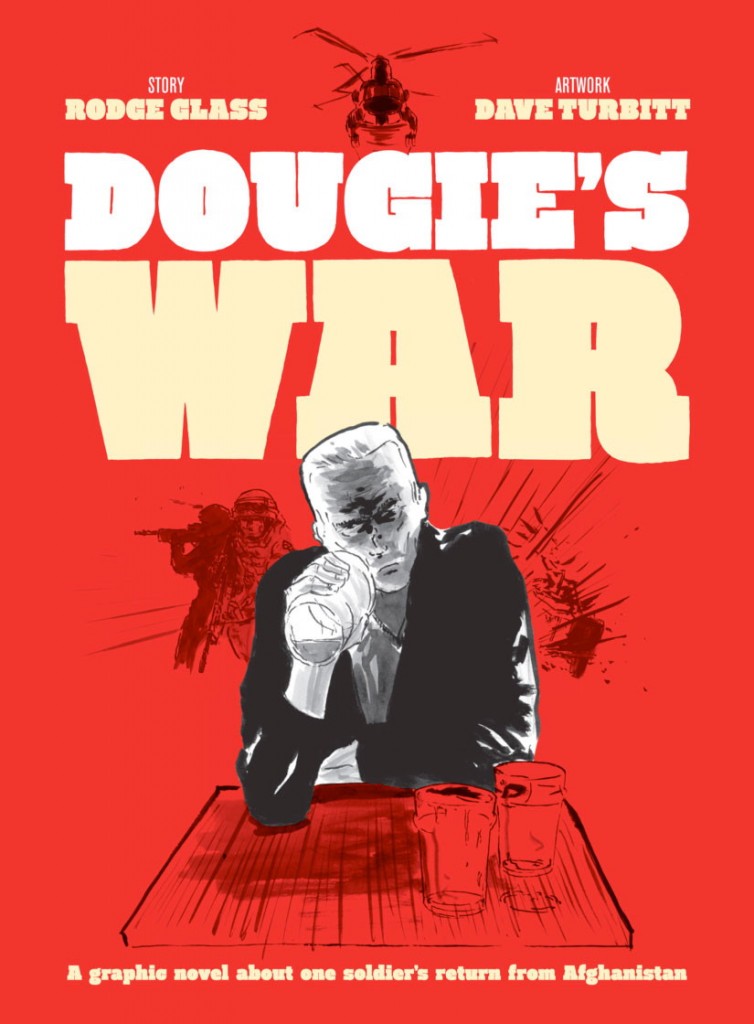

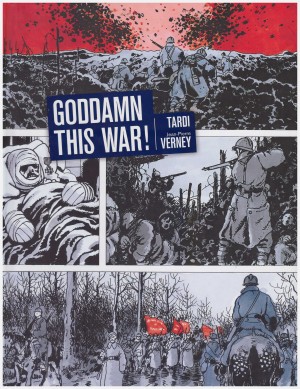

Dougie Campbell, after whom the book is named, is a composite, his experiences distilling those of numerous British soldiers who served in Afghanistan as told to writer Rodge Glass. His introduction notes how counselling services have improved for returning soldiers, but the underlying question is how effective that is in identifying post-traumatic stress among components of a culture that thrives on masculinity. And this is among those extensively trained to suppress emotion in order to cope with the horrors of combat.

Dougie served in Afghanistan and returns home to an initial warm welcome from friends who want experience reduced to anecdote, and who slip away as time passes. There is no support mechanism for someone used to it and now unable to cope, and matters are exacerbated by Dougie wrecking his knee climbing Ben Lomond, something he dreamed of while in service. He increasingly turns to alcohol, alienating the few who do care for him, but can’t ask for help.

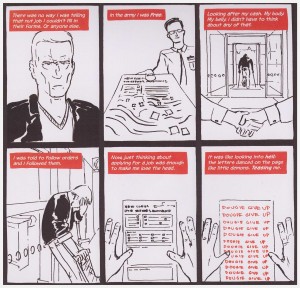

Dave Turbitt’s thin-lined naturalistic art in black, white and red is effective. He contrasts the expressive Dougie who’s returned to Glasgow with the stone-faced soldier that preceded this, and his depiction of the ghosts that Dougie carries with him is particularly memorable.

While caring, Dougie’s War is is no sentimental overcoat. Dougie’s problems make him at best an awkward character, and Glass is scathing of a society that has a place for soldiers, but that place isn’t back home in Britain. There are a very telling final couple of lines to the story section.

The presentation is novel, being a book form of linked internet material, with Dougie’s story only occupying around half the pages. There are reprints from Pat Mills’ and Joe Colquhoun’s Charley’s War looking at what would now be considered post-traumatic stress during World War One, an article with extensive interviews with those who’ve served in Afghanistan and Iraq, and Rudyard Kipling’s Tommy, an excoriation of public attitude toward soldiers. This scrapbook approach enlightens and informs, and it’s surprising that only You’ll Never Know has approached such a scrapbook this format.