Review by Ian Keogh

Her star has faded a little in the 21st century, but Djuna Barnes was a pioneering writer beyond the lesbian fiction with which she’s primarily associated. Fifteen years before the 1932 publication of Nightwood, the novel sealing her reputation, she’d been an innovative journalist in New York and a decade before it she proved an astute interviewer of the American ex-pat community in Paris. She led a turbulent life, both acclaimed and shunned at various points, and not without tragedy, which makes her a biographer’s dream, and additionally she’s eminently quotable.

Jon Macy though, is astute enough to look beyond the obvious headline moments, and delivers a rounded appreciation not ignoring her lesser qualities, such as a very modern lust for fame, unnecessarily acerbic putdowns and an ability to alienate friends and supporters. He doesn’t work through Barnes’ life chronologically, but sets a prologue in the 1930s before starting with Barnes arriving in New York in 1912, delivering extended trips to her past when relevant to the present. Even divorced from Djuna’s own story, that of her grandmother and her commune experiment in the late 1800s is remarkable, if manipulative and misguided. Yet that upbringing is used to highlight the fears of Djuna’s mother about what her daughter might become. Djuna, though, is more practical than her father.

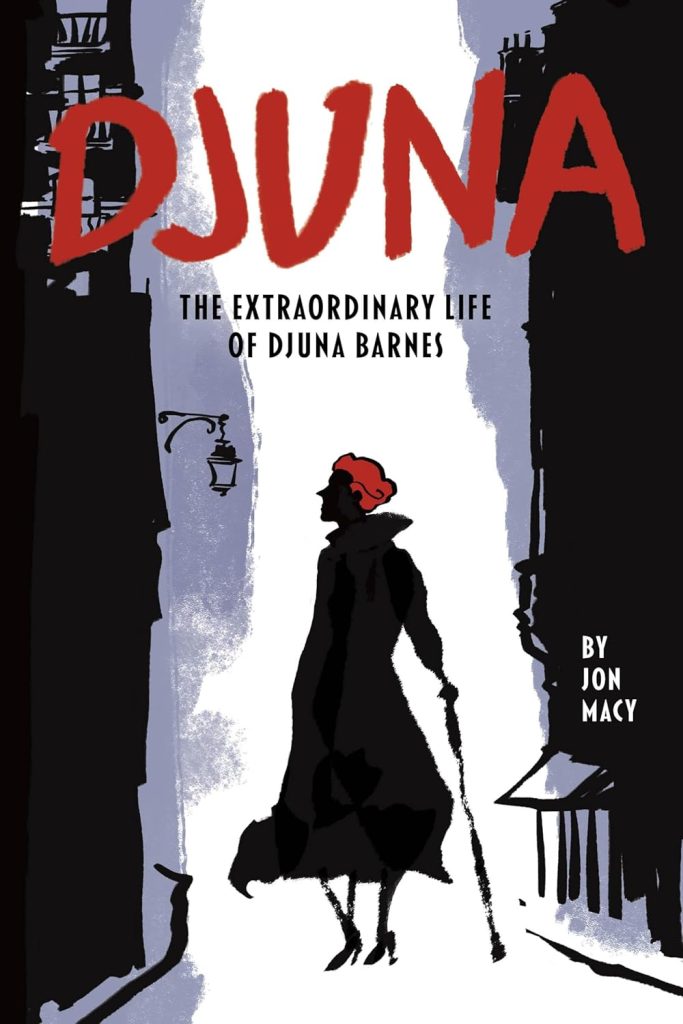

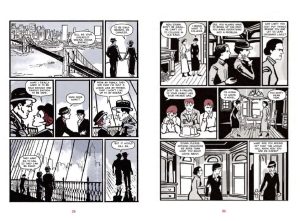

This is a dense graphic novel as Macy’s art is extremely precise, and every panel no matter how small swells with detail. Settings are rendered down to the bunching of a rug, the shade of an attic room and uneven cobblestones. Primarily black and white art is embellished by spots of colour identifying the Barnes family’s distinctive red hair in what has obviously been an incredibly work intensive project. It’s been worth it as every panel is a treat, and they’re supplemented by even more embellished pages introducing some chapters.

Immense talent coupled with impulsive and poor choices sums up Barnes’ career, and the more these impacted on her the more bitter, depressed and alcoholic she became. While her achievements shouldn’t be defined by those she associated with, the oddballs of the 1920s became artistic giants. Her place among them is essential in summing her up and Barnes associates with and frequently seduces poets, dancers. sculptors, writers, photographers, performance artists and painters, as the hedonism of her youth is reflected. Djuna encompasses so many others with Macy wanting to feature all their stories, and what stories some are, but a bigger flaw is Macy’s occasional personal intrusion, unable to resist comparisons with people he’s known. And there are small, but strangely obvious errors, such as “Farber and Farber”, sloppy for a publisher approaching its centenary.

At times comments regard events in the past that Macy’s not yet unveiled, but they’re all disclosed eventually. Barnes is a difficult person to come to grips with. An appalling youth through which gaslighting was a regular process certainly manufactured a biting tongue as a defence mechanism, yet it left her sometimes a bully herself, and Macy doesn’t excuse her dark side. As her self-destructive relationship with Thelma Wood plays out she’s also shown as a moth attracted to the flame. Yet would Barnes have been the same writer without her malign inspiration? Heiress Peggy Guggenheim is seen less, but equally influential in a different way.

Conscientious, incredibly well researched and utterly fascinating, Djuna is a powerful recognition of a magnificent talent who escaped humiliation to shine briefly before decades of dissolute disappointment.