Review by Ian Keogh

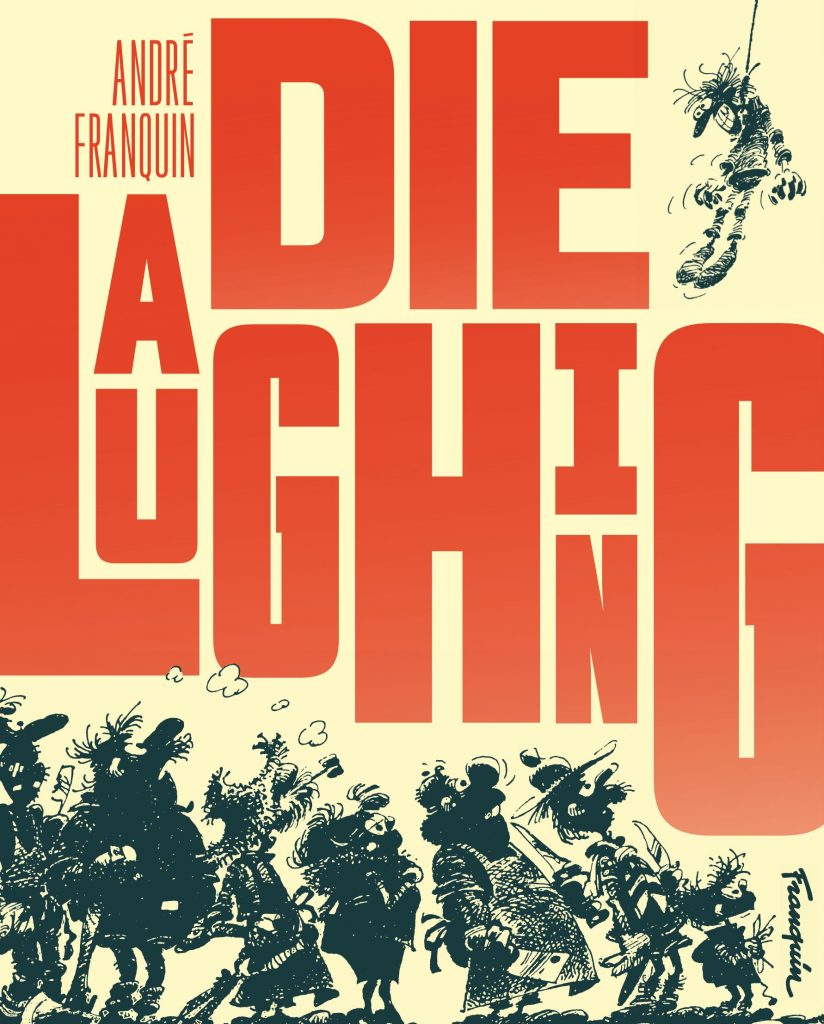

André Franquin is a great of Franco-Belgian cartooning, so good that there’s a viable case to be made for him being a better technical cartoonist than Hergé, yet until 2017 very little of his work over a forty year career had been translated into English. What is available is his light hearted childrens’ series (see recommendations), but Franquin’s adult life was scarred by depression, and the bleak places he visited during that are visible in the latter stages of Die Laughing. It combines what in France was originally two books.

It begins as a darker version of his popular Gaston series (the horrendously named Gomer Goof in English), where instead of the jokes resulting in pratfalls and outrage, fatalities are the result, the darkness extended by Yvan Delporte, best known for The Smurfs, supplying some ideas. They soon move beyond, however, with Franquin’s burning rage at the injustices of the world barely contained on the page, with others occasionally contributing ideas matching the tone.

Matters haven’t improved much in the decades since the material was created, with the parade of corrupt politicians prioritising self-interest, businessmen who’ll sell anything at a price and hypocritical clergy if anything ever more distressingly recognisable specimens today. Hunters are a particular source of ire, along with the tyranny of technology, while certain ancient motifs recur, the guillotine for one, surely the greatest symbol of man’s savagery,

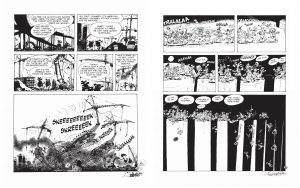

Despite this collection being a howl from the heart, you can just soak it in without ever reading as the cartooning is so masterful. Franquin slathers on the black ink to a density matching his outrage, yet there’s a delicacy, and a wonderful sense of movement to some pages. At times his work looks as if Ralph Steadman had repressed all his anger and instead concentrated on laying down every line perfectly, seething all the while as he filled in the black areas in Rotring pen. Underscoring both the talent and the anger is Franquin inventively varying his signature on every strip, incorporating another brief gag on that strip’s theme.

Cynthia Rose’s otherwise enlightening introduction perhaps suggests Franquin developed his observational desperation in isolation. A generation of cartoonists raised on his work had been pushing boundaries from the early 1970s, and there’s a comparable bleakness in the work of Jean-Marc Reiser’s far less structured illustrations, and in Christian Binet’s iconoclasm and use of black ink. The sample on the right could also be a Mordillo pastiche. Franquin, however, had always been unique, and adding his voice to the chorus of discontent raised the level of discussion.