Review by Frank Plowright

Delia has moved away from her farming family to study in the city, proving so capable at mechanical engineering that she’s employed as a research assistant. Professor Tak’s speciality is philosophy, but he’s convinced he can take a giant step from the theoretical to the practical by finalising a machine that decodes signals from the cosmos. It sounds crackpot theory, but it works. How will humanity change?

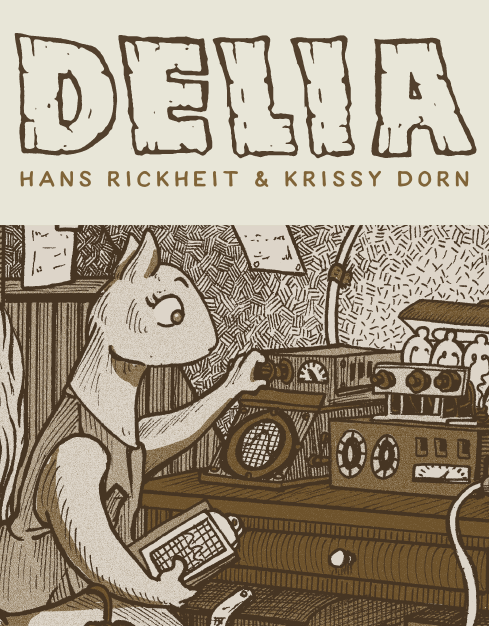

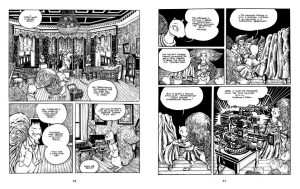

As her full name suggests, in German at least, Delia Eichhorn is a humanoid squirrel, one of a world exclusively populated by them in otherwise familiar trappings supplied in exquisite cartoon detail by Hans Rickheit, his style attractively inked by Krissy Dorn. He delivers a well-rounded and attractive version of the early 1950s down to cars on the streets and accessories in the kitchen. A capacity for detail extends to the multiple machine parts populating the local scrapyard, rendered extraordinarily precisely, and the imagination extends to the gloriously constructed nonsense machine seen on the sample art, through which communication occurs. Delia and other people are drawn to appeal, and have the rich emotional characterisation seen in the best Rupert the Bear books, and it turns out there’s a reason for them being squirrels.

Rickheit has been responsible for a succession of conceptually dense and disturbing projects throughout the 21st century, yet Delia could be seen as his commercial project. Such is his restless creative imagination, though, it’s as appealingly bonkers as his usual material, if not as viscerally disturbing. The paranoia of the early 1950s is used to investigate unknown territory, and that period is further evoked by introducing a mechanoid Godzilla, reflecting the era’s nuclear fears. Once again, it’s incredibly detailed, and there has to be some admiration for Rickheit spending so long drawing every mechanical part.

Delia herself is written as if the spunky heroine of a 1940s movie, perhaps a role Katherine Hepburn would play. She has a can-do attitude, an absolute confidence in her own abilities and the ability to do what’s necessary even if that’s not the best outcome for everyone.

Gears crunch as Rickheit moves from one plot to another, and some elements, such as the religious cult, serve no great purpose and would have been better dropped. Delia also too closely resembles the influence of 1950s SF films channelling the spirit of simpler times, yet also used to gloss over elements that could do with greater explanation. How do the public know so much about Delia’s involvement, for instance? By the end Delia reads as if a prolonged opening chapter of a larger story. A door has been opened and it can’t be closed again, and Rickheit’s done his job well enough that you’re likely to be frustrated by the lack of closure.