Review by Frank Plowright

Shane’s just been released from eight months inside a young offenders’ institution. He’s smart enough to realise it’s not that the world has changed, he’s the one who’s changed, and also smart enough to realise he shouldn’t have been dumb enough to have ended up there in the first place. However, once back on the estate it’s difficult not to fall into old ways, what with his best mate forever the source of temptation and his kid brother now that little more grown up.

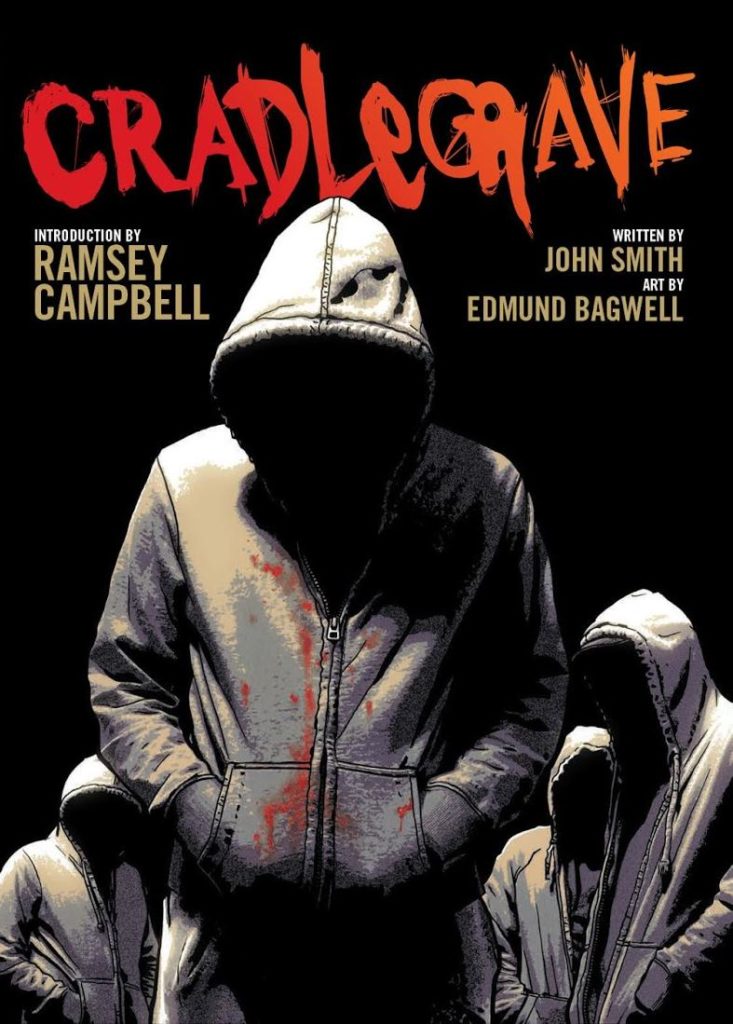

Cradlegrave is a completely atypical story for 2000AD, and it’s now difficult to believe it originated there as it has more of a Vertigo feel. John Smith throws in some cursory spooky elements, because it needed published in a science fiction and horror comic after all, yet what he’s screaming from the depths of his soul about isn’t a few pustules and shadows but the horror of an uncaring society. We never learn the real name of the Cradlegrave Estate, the title being taken from the graffiti replacing the missing letters on the road sign, but it represents countless examples scattered across the UK. Poorly serviced by public transport, they’re just far enough away from the city centre to make getting there difficult, so ensuring legitimate work is confined to the few opportunities on the estate. People are trapped in small identikit houses, poorly maintained by organisations whose priority is profit, not service. Out of sight and out of mind, they only hit the radar of society as a whole when a drug related murder hits the headlines, or a riot kicks off, and often not even then. We could do something, but we don’t, and while Smith is aware he might as well be waving a balloon in Orkney for all the difference a 2000AD story highlighting the issues makes, he cares enough to write it anyway.

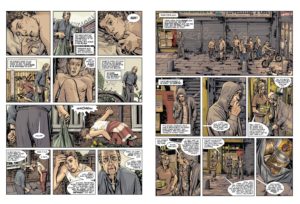

That passion is shared by Edmund Bagwell who put the hours into the meticulous recreation of abysmal squalor. The lives they’ve been allocated have taken their toll on his cast, with even the younger people having a world weariness about them, while the old have given up. Every surface is tagged, every garden piled high with uncollected black plastic rubbish sacks, and the washed out colours reflect the fading lives. The necessary horror element is a shuddering, repulsive creation, yet the point is made that this may be so, but it’s no worse than the normal life on the estate.

An occasional moment of bleak humour punctuates the narrative, such as a page taking a tour of neglect on a hot day. Right in the middle is woman with eyes closed tanning herself listening to Perfect Day through her headphones. As Smith and Bagwell continue, you begin to fear for Shane, even with his head screwed on, because this isn’t the type of story that has a happy ending. It doesn’t, not for everyone, but it has an appropriate ending, and that’s the weakest section. Smith has said what he has to say, said it again, and there’s really nothing other than quickly solving the problem and closing the door. It’s not greatly satisfying, but it’s true to life. We’ve had our glimpse and can go back to Superman now.

Cradlegrave is a thin book, and the story only occupies 75% of the pages, the remainder being process material, but quality’s what counts, not quantity.