Review by Graham Johnstone

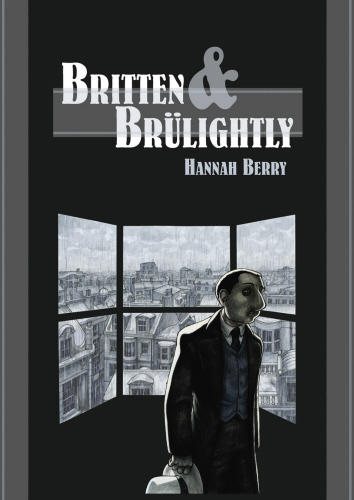

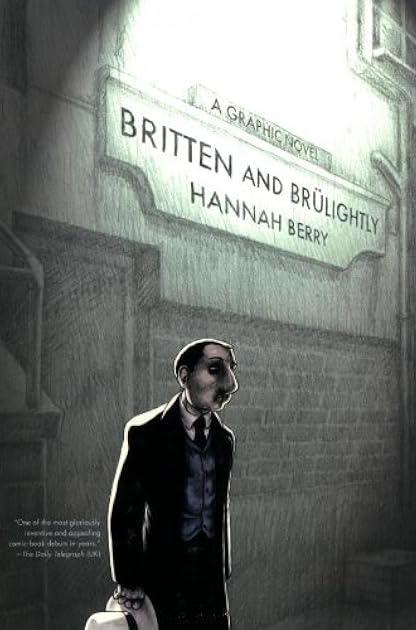

Britten and Brülightly is the first graphic novel by Hannah Berry, a murder mystery.

Fernández Britten, however, is an atypical detective, preferring to call himself a Private Researcher. He looks like Hercule Poirot, and in a humorous nod to his Belgian lookalike, is often mistaken for French. However, Britten (like Berry herself) has roots in Ecuador. In character, though, there’s little in Britten of the bombastic, ego-centric temperament Poirot’s own creator condemned in him. Britten’s cases are also less glamorous – typically domestic, with success involving bad news for the client, so explaining Britten’s nickname ‘The Heartbreaker’. Brülightly, according to the cover blurb, is Britten’s “‘unconventional’ partner”, but that’s quite an understatement. Avoiding spoilers, let’s say he offers a foil for Britten, without stealing focus. Unconventionally, Britten’s no action hero, and the book opens with him wondering if there’s a case that can even get him out of bed.

That case is brought by Charlotte Maughton, daughter of a publishing magnate. Her fiancé, who’s also her father’s assistant, has been found dead. Charlotte questions a suicide verdict, and suspects murder. Beyond this mystery, there’s a further hook of whether Britten’s findings will give Charlotte comfort, or heartbreak. The detection is mostly door-knocking, with a series of incremental findings revealing messy realities and venal acts, more often than deadly sins.

The time and setting is never stated. The cover image could be London, Paris, even Poirot’s Belgium, however, the incessant rain suggests Britain, and we later see an iconic British phone box. Crime plots often drive explorations of place, but here the ambiguity of locale is hardly noticeable, and adds universality. The story might almost be set any time, though some vintage vehicles suggest the inter-war ‘Golden Age of Detective Fiction’, and some of the plot and stakes make more sense in that less permissive era.

Berry understands the detective genre well enough to thoughtfully update it. She shuns the righteous heroics of the hardboiled style, in favour of the and moral uncertainty of noir. Britten’s troubles include his burden of ‘Heartbreaker’ for his clients. His own heart, though, is hidden, perhaps broken long ago. Brülightly’s bawdy banter falls dead at his partner’s feet. Britten’s main relationship suggests an enduring commitment to someone lost, and there’s no hint of any frisson between detective and widowed client. Avoiding such clichés, including male egotism and macho posturing, surely broadens contemporary appeal. The action is similarly restrained, the lack of showy set-pieces, like car chases and shootouts, elevating Britten and Brülightly from pulp, to literary mystery.

Berry’s acknowledgements note advice to “rewrite and rewrite…” and that’s reflected in an elegantly scripted, and tightly paced book. She leaves the reader guessing until the closing pages, and the ending satisfies as both crime plot and character story.

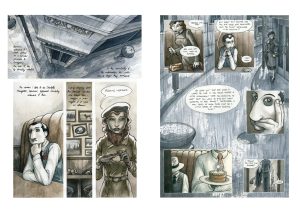

The art, like the story, avoids binary black and white in favour of celluloid noir’s shades of grey, here layered in ink washes. Trained as an illustrator, Berry puts solidly designed and drawn characters into convincing settings, albeit drowned and obscured by rain. Traces of washed-out colour add to appealing and effective pages.

Berry’s layouts also evoke film noir, with whole page images often cut horizontally into ‘widescreen’ panels. This sends the eye across, down, across… as if scanning the scene for clues and threats. Cropped panels and oblique angles further build tension and disorientation, drawing readers into her neo-noir narrative.

Britten and Brülightly is an impressive debut. Adamtine, and Livestock followed, before Berry transitioned from creating comics to championing them, including a term as the UK’s Comics Laureate.