Review by Frank Plowright

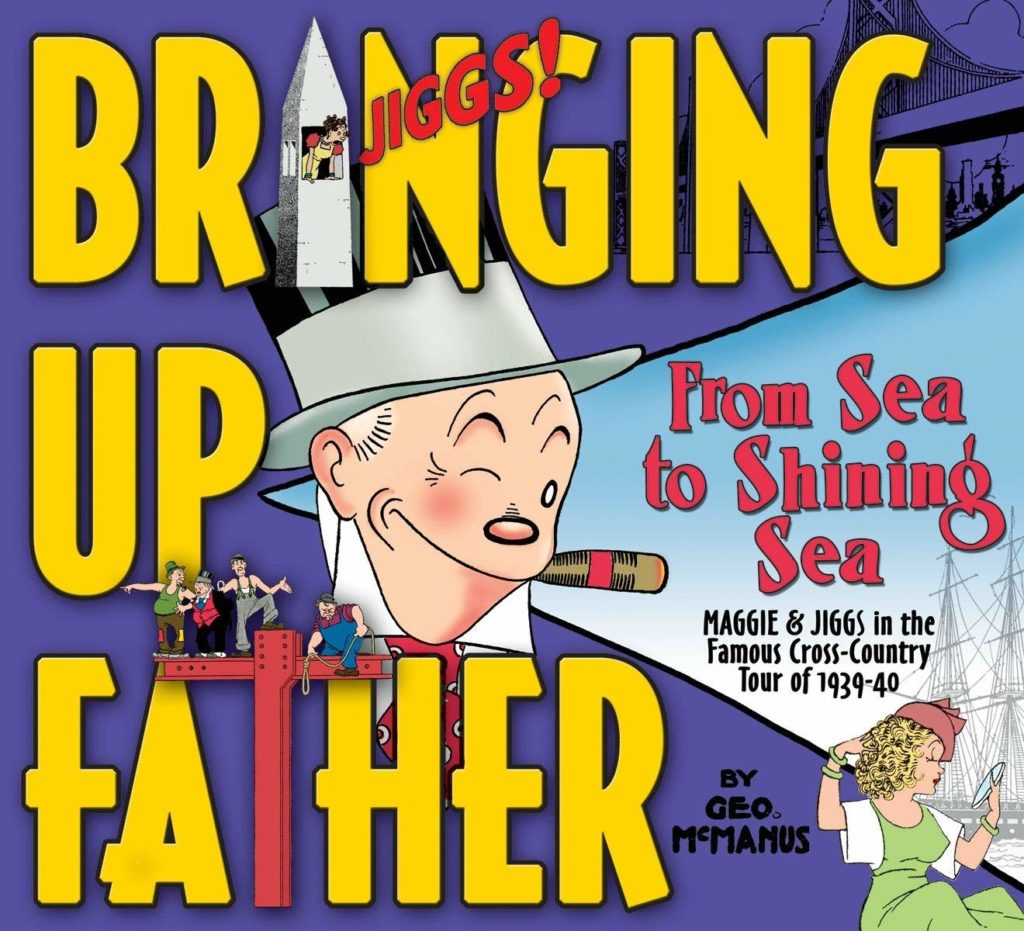

From the 1930s to the 1950s Bringing Up Father was a phenomenally popular newspaper strip racking up a massive circulation. It provided the slapstick antics of newly minted millionaire Jiggs, whose wife and daughter adapted easily to their new lifestyle, while Jiggs himself was never happier than back in his old haunts, or meeting old mates, always dressed for comic effect in his dinner jacket, spats and top hat. George McManus was a master cartoonist who impressed Hergé among others, and along with assistant Zeke Zekley touched something universal, affording both of them a wealthy lifestyle to match their lead character.

For all that, only two volumes of IDW’s prestigious Library of American Comics reprints have appeared. This covers strips from 1939 to 1940, and Of Cabbages and Kings takes care of 1937-1938. Is McManus’ humour so tied to the times that it no longer resonates? Certainly the idea of the henpecked husband as a source of humour is one consigned to history, but the drunken behaviour used in earlier years had been phased out to be replaced by a detached bemusement at the world.

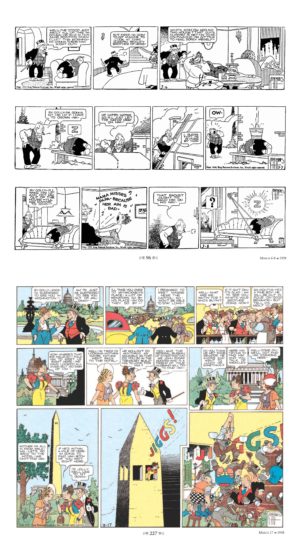

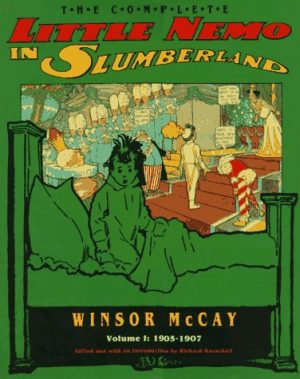

From Sea to Shining Sea can be opened at any random page to present McManus as an exceptional cartoonist delivering buckets of personality, but topping that is his astonishing sense of design. Even restricted to three panels on the black and white daily strip, the patterns on Maggie’s dresses are bold and ever changing, art deco influences most prominent. However, it’s the Sunday colour pages that best showcase a first rate graphic imagination. McManus packs the panels without them ever being messy, while every person featured is dressed and posed differently and has a unique expression. There’s an extraordinary sense of life, sometimes accompanied by bright colour, yet toned down if McManus wants a sunset scene with some of his beautiful silhouettes. Carl Barks surely paid attention. And while the tone might mine the greatly trodden path exceptionally well, McManus was no conservative when it came to artistic experimentation. The colour pages are brimful of chances taken, and it’s a rare one that doesn’t succeed.

As if the work put into the art wasn’t difficult enough, McManus complicated his life by sometimes running different continuities over the daily and Sunday strips. The daily strips are standard gag material, McManus running through every possible permutation on a theme before moving to the next topic, while more panels on a Sunday strip afford a greater lead-in to the jokes, although slapstick remained his stock in trade until the end.

Very occasionally there’s a strip that’s lost its charm – Jiggs being pally with President Roosevelt is just showboating – and what can be defined as the comforting familiarity that touched a nation can also be seen as predictability. Some jokes have always been comfortingly obvious in daily newspaper strips, yet relationships, reactions to babies, and social variations also remain as they always were. He may dress differently now, but the type of upper class English idiot McManus exaggerates is these days to be found on Made in Chelsea, while the freeloading layabout represented by Maggie’s brother would today be stoned. Interestingly, it’s the travelling that made this sequence so memorable, and it worked wonders for the art, but the better jokes are actually found before Jiggs and Maggie set off on their trip.

The quality lies well beyond dispute, but ultimately you’ll have to make up your own mind if Jiggs’ time has passed. The sample art pastes three consecutive daily strips above a Sunday page, both representative verve and style, and display why Bringing Up Father should be remembered.