Review by Frank Plowright

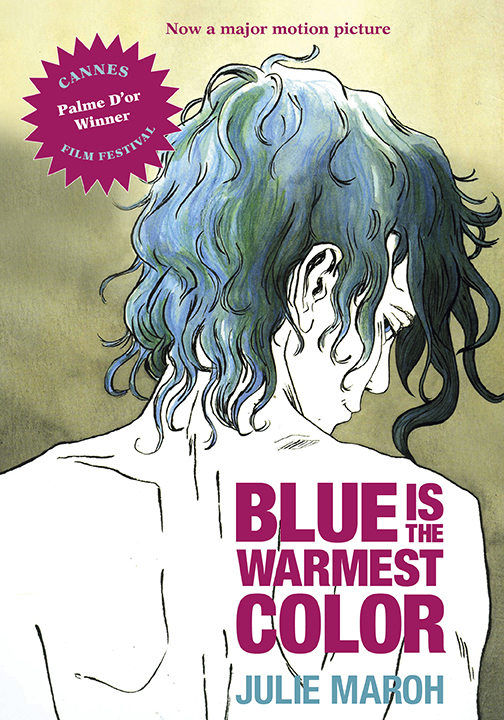

Julie Maroh’s début graphic novel has become quite the sensation, in no small part due to the film based on it winning the Cannes Film Festival’s prestigious Palme D’Or. That, though, is a different beast.

The graphic novel, despite some trappings, drops squarely into the traditional romance genre, except that the romance is between two women. It doubles as a coming of age story as schoolgirl Clementine, fifteen as the narrative begins, is tentative and uncertain about accepting her gender orientation. She’s realised that she’s incapable of responding emotionally to a boy who’s keen on her, and her life changes when she finds herself outside a lesbian bar and works up the courage to walk in. She briefly meets Emma, confident, attractive with dyed blue hair, and in a relationship with a jealous girlfriend.

Maroh takes the interesting narrative decision to reveal from the start that Clementine is dead. Her story unwinds via Emma reading her diaries in the family home, where her reception is frosty, and the insight provided for Emma honest and distressing. Clementine’s parents are the weakest element of an engaging story, their lack of understanding and intolerance painted in broad strokes and very much a convenient device. They do prompt one fine moment, though, as Emma, attempting to provide some solace to Clementine’s mother, notes that were Emma a guy Clementine would have fallen in love with her anyway. The overall tension is maintained despite the revelation as this is a considerably older Emma, her hair now more conventionally blonde, leaving plenty of time to elapse.

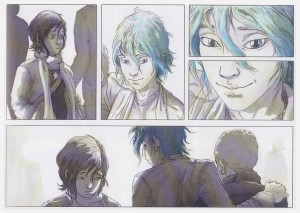

Not far removed from her teens when she created Blue is the Warmest Color, and confident in her own sexuality, Maroh has vehemently denied the story is any way autobiographical. Her naturalistic rendition of teenage uncertainty and insecurity shines through a convincing translation from Ivanka Hahnenberger, and Maroh is gifted at conveying emotion via facial expression and body language. She paces the story well, and distinguishes distant past, more recent past and present by the simple method of colour application. Emma’s hair is the only colour to be found on many pages.

It should be noted that this book is at considerable variance with the later film, which some consider takes considerable liberties in overly sexualising a warm and heartbreaking story to invite prurient interest. As with most artistic endeavours, stick with the source.