Review by Frank Plowright

The Black Panther has become an increasingly problematical character over the years. When introduced by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee in 1966 he was groundbreaking as an African superhero ruling his kingdom of Wakanda, but his creators gave little thought to his background beyond the needs of the plot. It’s reprinted here if anyone needs convincing. In more recent times questions have come to be asked about why T’Challa, the Black Panther has no real African culture about him.

In Ta-Nehisi Coates Marvel hired an intellectual heavyweight with impeccable writing credentials to solve that problem, and he makes an opening statement by naming his story after Steven Hahn’s Pulitzer Prize-winning history of black America. One wonders what any new readers he may have brought to the Black Panther have made of his version, as there’s certainly no concessions to them. They’re greeted by page after page of portentous captions, overwrought dialogue that at times verges on the laughable, philosophical justification for every deed, and a story that’s indescribably dull.

The basis of it is that a women who serves among the Panther’s elite guard is sentenced to death for her own murder of a village chief known to prey on children. A colleague considers this adherence to law to be unjustified, rescues her friend and lover, steals some experimental armour, and they set about uniting the disgruntled and disenfranchised of Wakanda. This is a country suffering the effects of natural disasters and attacks from cosmic powers, where the population are quickly convinced their King has deserted them, and revolution is fermented. Coates switches his attention around several people at greater or lesser odds with the Black Panther, and the tedium is disappointing as he has valid points to make. One is a consideration of why people turn to extreme organisations as the solution to their grievances, and the manipulation employed in some instances, and another is the treatment of Wakanda as nation rather than a convenient backdrop.

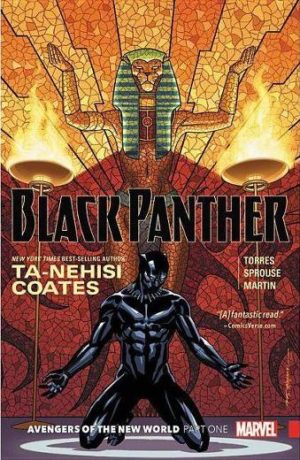

Brian Stelfreeze ensures the Panther’s environment reflects both his heritage and his established technological supremacy. The art throughout holds great appeal with eye-catching designs, good visual characterisation and interesting layouts. He’s helped greatly by the thoughtful colouring of Laura Martin, who deals largely in brightness, but also works in distinctive palettes for different areas and moods.

Among the process notes in the back Stelfreeze remarks that Coates is still evolving as a comics writer. It’s to be hoped that this evolution accelerates, as surely a fundamental expectation of a superhero graphic novel, beyond verisimilitude, beyond political correctness, beyond moralising, is some excitement, and that’s entirely absent from this first volume of A Nation Under Our Feet. Is Book Two any better? Alternatively the entire story is avilable in paperback, also as A Nation Under Our Feet, or this volume as a standalone as part of the Ultimate Graphic Novel Collection in the UK.