Review by Frank Plowright

Rodolphe isn’t a writer likely to take the direct route, and having begun Black Mary with the adventurous Lord James, the title character eventually appeared toward the end of The Departed. That volume concluded with Black Mary’s pirate ship about to take on a substantial and well defended craft to steal treasure, but Rodolphe surprises via delivering the battle in drips and drabs from hindsight. That’s because there’s a larger issue to address.

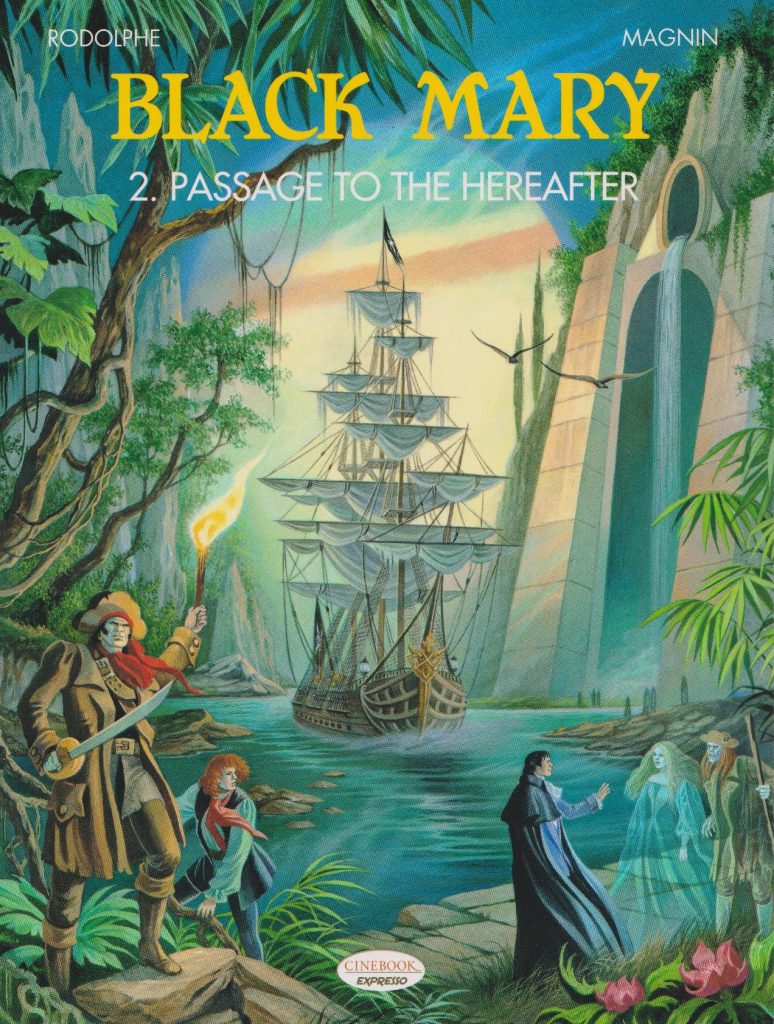

Black Mary began with Lord James investigating the alleged presence of ghosts, and it’s not deep into Passage to the Hereafter before an explanation is forthcoming. Black Mary is able to avoid pursuers via her discovery of an uncharted island, and it’s here the dead congregate before moving onward.

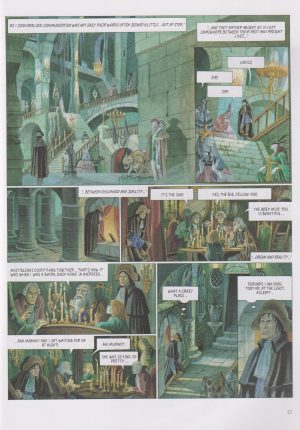

As before, there’s an awkwardness to Florence Maginin’s painted art, although it’s developed a little from the first volume. While the workrate and detail is welcome, the composition of many individual panels remains structured as if period fine art, which impacts on the storytelling, They’re too crowded, and there’s not enough definition and contrast, leading to a lack of depth.

Rodolphe takes some strange turns in a meandering story. The possibility of communicating directly with the dead is too good to pass up entirely, but like other aspects it turns into a dead end, although true to the classical romanticising of death. To compensate, the sequence features Magnin’s best art, a few pages of impressive architecture on a grand scale. The alluring Leonora is a disruptive presence prompting an almost satirical comment on the idea of 18th century masculinity, but James apart, characterisation is slim.

There’s the feel of Black Mary being plotted on the hoof, as James’ narrative eventually becomes anchored to a place, and revealed as his recollections of the past. He’s continued to be a successful novelist when a final adventure beckons, this almost a pastiche of European period dramas, leading to a preposterously sentimental ending.

Over two volumes this shines in places, but never lingers anywhere long enough to build toward the intended tragedy.