Review by Graham Johnstone

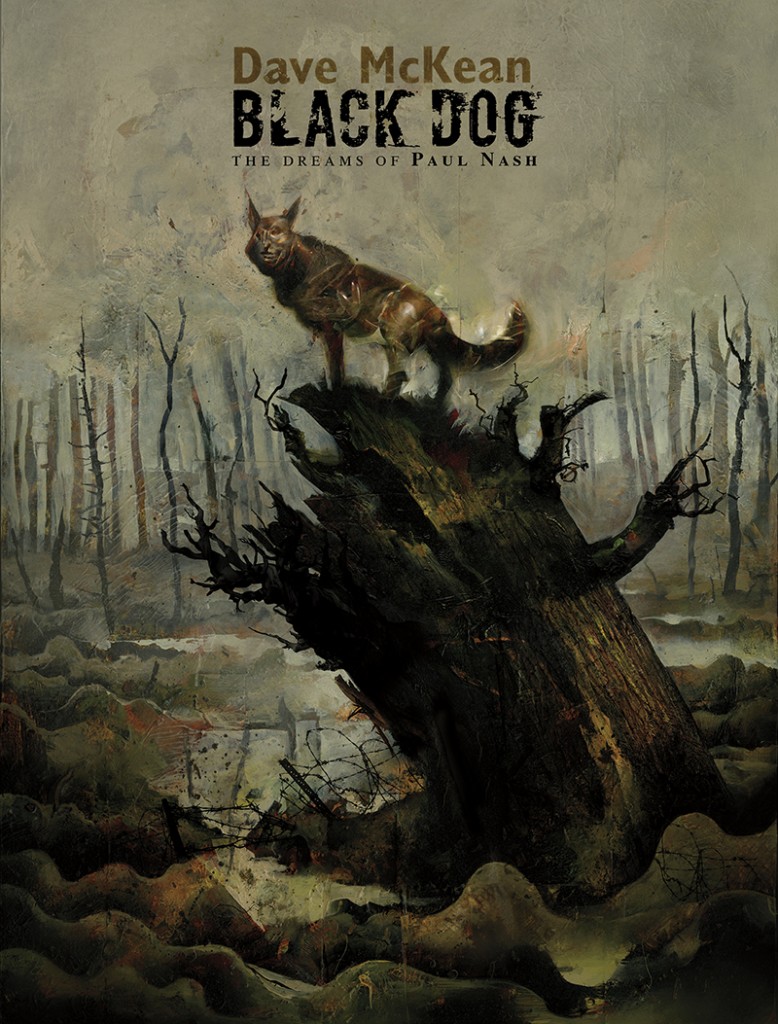

Black Dog is a biography of English painter Paul Nash, the title a symbol of the depression that haunted him. Centred on the trauma of World War One, it was commissioned to commemorate the centenary, along with a Nash retrospective at London’s Tate Gallery. The commissioners secured, a prefatory note tells us, their ‘dream’ artist in Dave McKean.

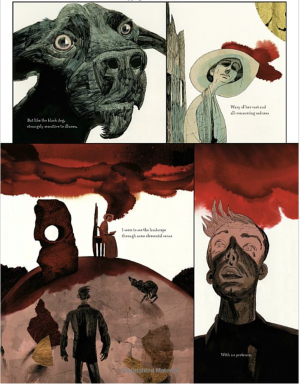

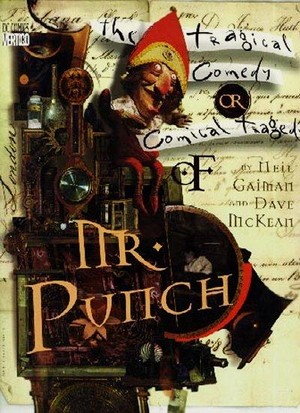

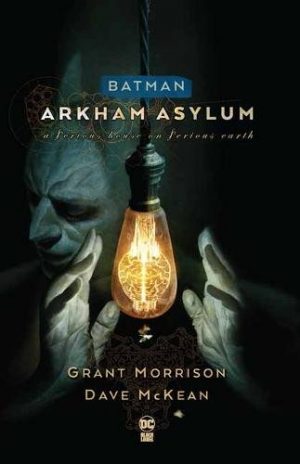

Those familiar with McKean will at one level know what to expect – mixed media techniques, (still unusual in comics), combining watercolour, collage, photography, and digital imaging. McKean’s creative and technical skill as an image maker is undeniable, if perhaps tending to the theatrical and overwrought. McKean’s recognisability, though, can mask his range of style and tone as he’s ever-changing – even within a single book and here, far too engrossing for such concerns to arise.

The art is in the spirit of Nash, but McKean’s own standing as an artist lets him draw from the source without feeling too constrained or reverent. The nearest comparison within the emerging artist biogrpahy genre, is Dali, by the similarly admired Baudoin, who adopts the spirit of surrealism, without his subject’s ‘old master’ rendition of it, drawing instead on the wider movement’s diversity of styles. To those who know Nash, the imagery here is recognisable: the landscapes mixtures of the natural with the man-made and indeed man-destroyed. The distinctively muted palette reflecting English light and weather. Nash was famously critical of his figure drawing, an ‘inability’ that led to the distinctiveness and coherence of his largely unpopulated work. A graphic novel without figures though, would be an extreme move, and with no sources in Nash, McKean draws on other period artists. His charmingly elongated, limp-necked figures, for example, evoke Roger Fry’s depictions of ‘English eccentric’ writer Edith Sitwell; and his panoramic battlefields – resemble dark takes on Stanley Spencer’s man-machine industrial harmony. A single spread in the introduction renders the titular dog distorted by forces from Italian ‘Futurist’ Boccioni, while the dream imagery evokes the haunting collage-born landscapes of the Surrealist Max Ernst (featured image). In chapter 2 he draws on the cut-outs of Matisse, and elsewhere, the German Expressionist woodcuts that inspired Nash’s contemporaries. That’s quite a range of stylistic sources – perhaps unmatched in comics – successfully channelled to capture the subject’s landscapes, by turns pastoral, mystical, and gothic; the period’s defining trauma of the war; and the effects of all this on Nash’s already fragile psyche.

As a writer, McKean is less established, and the appended author bio and bibliography highlight his track record mainly as illustrator/collaborator. Non-fiction, though, offers more to build on than fiction’s blank page, and Nash’s life has already been shaped by memoir and biography into narrative arcs and key moments. McKean also channels the era’s literary innovations, the stream of consciousness evoking James Joyce or – closer to home – Virginia Woolf, along with the contemporary War Poets like Wilfred Owen (indeed McKean’s text – poetic and arranged in short lines, often crystallises into verse). This is perhaps best exemplified in Black Dog by a scene where young Nash fails to understand geometry, resulting in a remedial teacher’s blow, which segues into a collapse on battlefield barbed wire. The content evokes Nash’s personal trauma, and the style, his artistic context, proving McKean’s writing a fine match for his art.

Black Dog, then, combines psychological biography, with a portrait of a time and place, and renders it all in appropriate and evocative styles. Its channeling of this key period of the avant-garde may reduce its appeal, but it deserves a much wider audience than simply fans of either artist.