Review by Frank Plowright

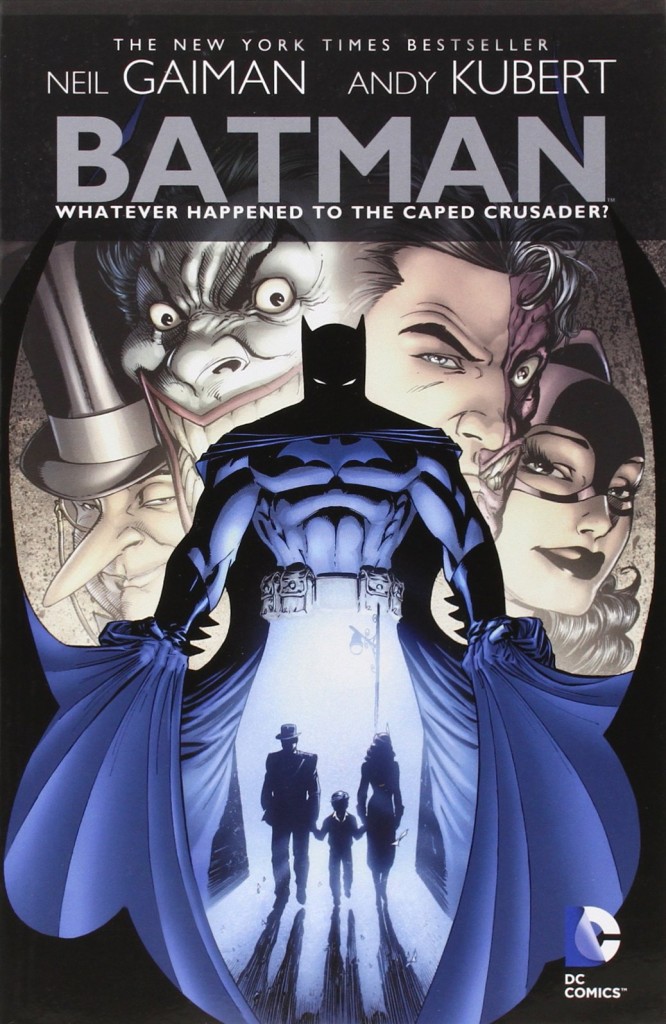

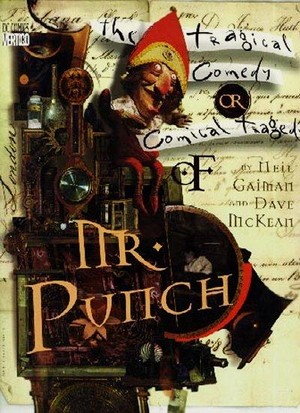

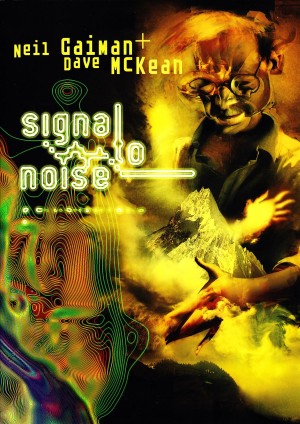

The title poses a question, and the content set one for DC. How do you create a Neil Gaiman graphic novel from just two comics? You weld the 2009 comics to any Batman associated material produced by Gaiman. Most dates from the late 1980s when he embarked on a comics writing career.

The title feature is deliberately structured as a darker reflection of Alan Moore’s earlier ‘Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?’, a similar eulogy for a temporarily deceased icon, and one immediately inviting comparison. It’s an odd conceit.

It’s further an odd leap of logic to imagine Batman’s friends and allies would willingly mix with those who’ve tried to kill him time and again, but Gaiman’s tour de force is the exploration of dreams, isn’t it? One after another delivers their impossible memories of Batman, the friends considerate and loving, the enemies deceitful, yet respectful, each contradicting the other as they claim to be responsible for Batman’s demise or present for his final moments.

Adam Kubert’s illustration is excellent in matching the assorted moods, sometimes deliberately aping other artists, sometimes instructed by script as Gaiman toys with the myth of Batman. For all that, it’s extremely bitty, with some nice elements that you wouldn’t see in a standard Batman comic, the beginning car parking whimsy for one. Despite some poetic touches, though, it’s unlikely to live up to Gaiman’s hope in the introduction that it will survive the decades as the final Batman story. While a deliberate contrast, nor is it the memorable epitaph that Moore supplied for Superman.

Perhaps that’s because Gaiman said everything he wanted to say about Batman in 1996 when collaborating with Simon Bisley. They cast Batman and the Joker as actors playing roles, a theme that recurs in the title story, and says almost as much about Batman in seven pages as the title story does in over fifty. Bisley appears to have been looking at Kevin O’Neill’s art before picking up his pencil.

The remaining work dates from the late 1980s and displays Gaiman as a writer of great promise and one able to switch tone, which is far rarer than it ought it be. There’s an ordinary tale of a TV producer making a documentary about Gotham’s villains, lacking a dynamic sparkle as drawn by Mike Hoffman, and rendered even more awkward by missing two of the segments it originally framed, written by other creators. The third deals with the origin of the Riddler, drawn by both one of comics’ great stylists and one of its great lost talents, Bernie Mireault, whose mastery of bathos is evident here. Elements of this strip are also reflected in the title story, and it remains a very engaging piece with a charismatic Riddler confounding expectation reflecting on a long career.

Going back still further we have ‘Pavanne’ the first published work at DC for both Gaiman and Mark Buckingham. This predates Poison Ivy’s current green skinned incarnation, and is a clever tale of fatal obsession, reconfiguring Poison Ivy’s origin by the simple method of having her claim to have fabricated some of what was previously known. Buckingham’s not quite the finished article, yet confidently adaptable considering how early this was in his career. The story serves as a workout for Gaiman, who’d use her again in his next DC project, Black Orchid.

None of this content is prime Gaiman, and if picked up on the basis of his name alone may well disappoint.