Review by Ian Keogh

The shapeshifting lump of clay may not be the first of Batman’s villains to come to anyone’s mind, but he’s a pedigree creation whose adventures began in the 1940s, although that was a different Clayface. There have been several, and all are represented in this anthology.

The first Clayface appeared just a year after Batman himself, and by the same creative team of Bill Finger and Bob Kane, a killer on a film set wearing the costume of a character named Clayface from an earlier film. Finger’s script features misdirection, but as the character recurred, regular Batman readers won’t be fooled.

Finger was around long enough to introduce the second Clayface in 1961, this time Matt Hagen able to transform his body into any number of clay shapes. He comes with the clever restriction of constantly having to renew his powers, but Sheldon Moldoff’s art is very old-fashioned.

In the 1970s Marshall Rogers took the look of the 1940s Batman, but updated the style into something very modern, and now timeless. He and Len Wein introduce the third Clayface, Preston Payne, a far darker creation steeped in gothic melodrama, although Wein borrows from Two-Face’s origin. It’s very readable still.

That’s not the case for Mike W. Barr and Jim Aparo’s 1980s revision for the shape changer who menaces the Outsiders. Sondra Fuller masquerades as Looker to attack the team on Kobra’s behalf, but this is by the numbers.

It’s at this point the collection begins to run into problems. The modern era stories are generally better, but so many repeat the origin sequences presented earlier. Hagen’s origin appears in full three times under different creative teams, and again more briefly as part of a further story. It’s only twice apiece for Karlo and Payne, but theirs are also contracted in the later effort. Nice as it is to see Bernie Mireault or Mike Mignola drawing Hagen it’s not so great that it merits the repetition.

Doug Moench and Kelley Jones supply the origins in brief, but move things on by revealing Payne and Fuller have conceived a child they named Cassius, a sly joke on Moench’s part. So is much of the remainder, although efficiently couched as tragedy with Jones’ style well suited.

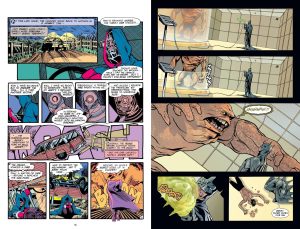

A. J. Lieberman and Al Barrionuevo (sample art right) are responsible for the longest inclusion at four chapters, set during the era Hush first manifested to menace Batman. It treats Clayface as more of an abstract rather than a living being, and it’s rather a shame it appears in a collection with the Clayface name on the cover as Lieberman perpetuates a mystery well if you’re unaware of what’s coming. Unfortunately, though, as good as parts of the story are, they’re part of a larger plot that takes priority, some aspects of which don’t connect in isolation, and they remain unresolved here.

Everything draws to a close with John Layman and Cliff Richards from 2013 and the first ever solo Clayface tale, as Karlo attempts to curry favour with the Secret Society. It’s fun without ever stretching the imagination too far.

As individual stories there’s nothing poor here, but they combine for a profoundly unsatisfying experience due to repetition or a dependence on an awareness of other plots being required. Could this not have been avoided?