Review by Frank Plowright

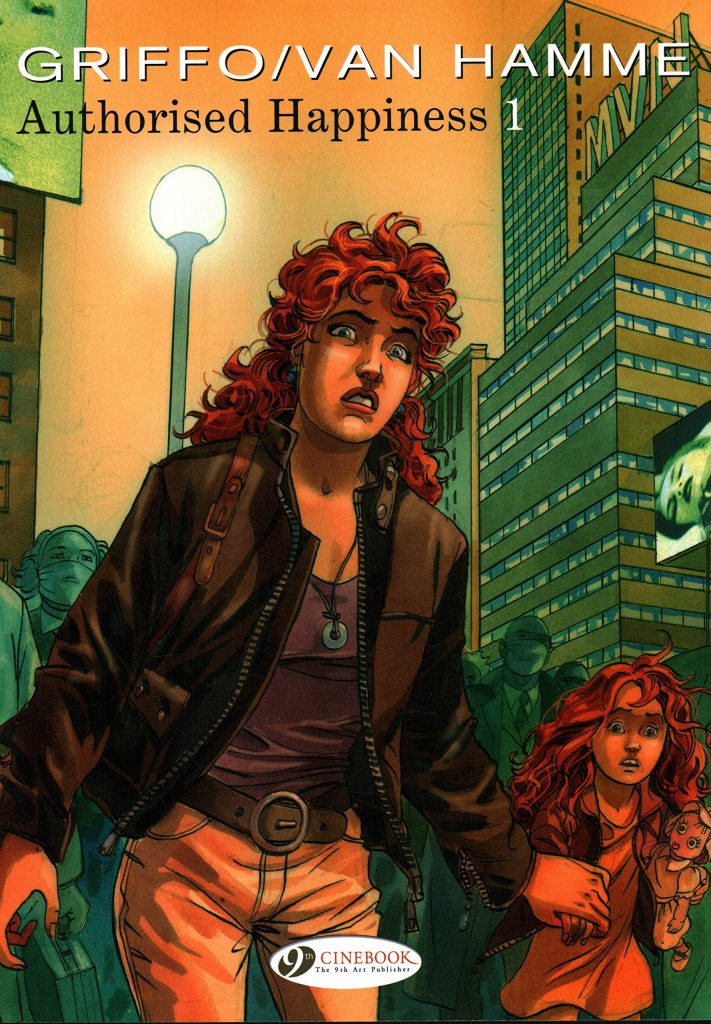

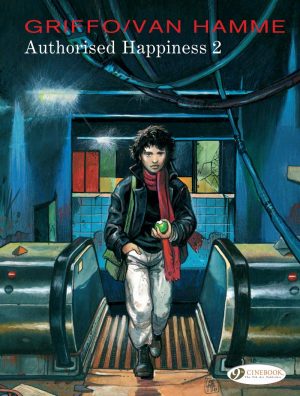

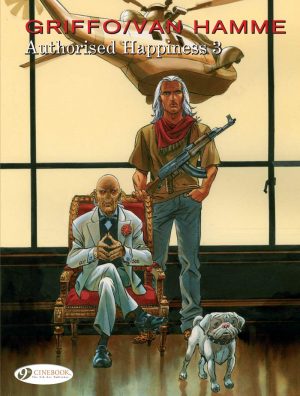

In a gloriously successful career Jean Van Hamme has written just about every type of comic genre there is, but he’s best known for his combinations of action thriller with mystery in long-running titles like Largo Winch and XIII. However, fans aware of his back catalogue hold Authorised Happiness in special regard. Complete in three volumes, it’s a selection of six connected short stories with a full album closer, all set in a puzzling and frustrating world of bureaucratic procedures used for purposes of control, and although written in the 1980s there’s little about it that doesn’t still resonate. It’s pleasing that Cinebook have also made the effort to translate Van Hamme’s introduction to the collected edition, explaining how the series came about.

The back cover blurb refers to the notion of the Welfare State running out of control, but Van Hamme’s world is more complex than that. The entire sinister tone is set in the opening chapter where after eight months of unemployment Francis Morton finds a new office job. His task is to compare two sets of figures and report anomalies, but he can’t figure out exactly what the General Analysis Company does. It nags at him, then becomes an obsession, but his enquiries are frustrated at every turn by some form of bureaucracy.

That’s followed by a look at overly intrusive medical police, anonymous individuals in protective gear enforcing prescriptive health, sanitary and safety rules. There’s a way to avoid those rules, but it involves de-registering, and is that really advisable? One of the issues is the state allocated holiday, which is investigated in the final inclusion.

Artist Griffo (Werner Goelen) is an extremely accomplished exponent of the Franco-Belgian shadowless school of art, excellent at devising a considerable selection of easily separated characters, and filling the backgrounds of panels with the details showing how they live. There’s some stiffness on the unfortunate Morton’s story, but that soon disappears.

Mentioned several times in the course of the shorter stories is the controlling regulations being introduced because previously society was a mess of confusion and contradiction, and the rules ensure a happier life for the majority. Van Hamme’s in-story justification remains very contemporary, the downside the majority don’t care about being, of course, the fate of those who don’t want to conform and slip through the gaps. Authorised Happiness isn’t comfort reading, but it is very prescient for work produced in the late 1980s, and that’s even more the case in Authorised Happiness 2.