Review by Jamie McNeil

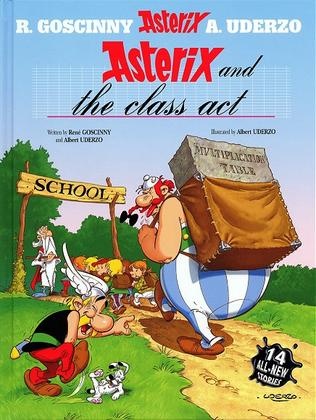

Asterix and the Class Act is the first collection of Asterix short stories, most of which had not been widely circulated, or even translated from French. At least eight were previously published in the shorter French collection of ‘La Rentree Gauloise’, some were also featured in promotional publication ‘Astérix mini-histoire’, and nearly all of them had been serialised in French magazine Pilote. René Goscinny wrote most, with the remainder written by Albert Uderzo, the quality ranging from excellent to okay.

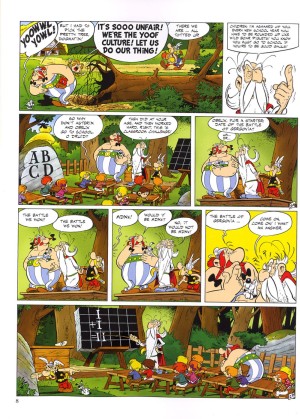

The stories don’t run in any particular order, so let’s just start with the Goscinny and Uderzo collaborations. The opener is untitled, originally published in Pilote as an announcement page for The Big Fight that catches the attention. The title story is a very funny and relatable parody concerning the start of the school year. ‘In 50 BC’ was originally printed in National Geographic (1977) as a companion piece for an article on the Gauls to introduce Asterix to an American audience. ‘For Gaul Lang Syne’ looks at ancient festive customs, Obelix trying to sneak a kiss from Panacea with hilarious results. Equally humorous is ‘Mini Midi Maxi’ (1971) written for French magazine Elle, Mrs Geriatrix the centre of attention much to Impedimenta’s chagrin. It’s an excellent example of how well Goscinny could write a narrative that contradicts the actual story to hilarious effect. ‘The Mascot’ (1968) stars Dogmatix whose popularity had grown since The Banquet, while ‘Latinomania’ (1973) is Goscinny’s funny and informative stab at the growing concerns of French academia at the spread of “Franglaise” (French interspersed with English). ‘The Authors take the stage’ section consists of ‘The Obelix Family Tree’ and ‘The Birth of an Idea’, covering the periods of 1962 to 1963. Creators were expected to self-parody which definitely helped connect the readers. More of a Franco-Belgian tradition, it lacks the same effect in English but both are brilliantly illustrated and yet individually unique.

Uderzo wrote ‘The Birth of Asterix’ (1994) to celebrate 35 years of the series, introducing Asterix and Obelix’s parents for the first time although they featured in Asterix and the Actress released prior to this. It’s most notable for giving Asterix and Obelix the same birthday, previously separate occasions (Obelix and Co.). ‘Chanticleerix’ (2003) features Dogmatix, a Gaulish cockerel and a Roman eagle. Uderzo was always very good at giving his animal cast a life of their own and this is no exception. It’s funny and well illustrated, certainly better than some of Uderzo’s full length solo efforts. It’s easy to forget that Uderzo was a very talented artist and two stories in particular highlight this. ‘Asterix as you Have Never Seen him Before’ (1969) was a response to letters offering “helpful” or just snobby critique. What you see is just how good Uderzo was in his day, employing a variety of styles to answer the critics. ‘Springtime in Gaul’ illustrates how detailed and inventive Uderzo could be, and while his story, lettered by Goscinny, is quaint it’s exemplary cartoon work.

Asterix’s cultural influence is impressive and even in fair stories, like ‘The Lutetia Olympics’ (1986) commissioned by Jacques Chirac to help with the 1992 Parisian Olympic bid, shows how important the character is to French identity.

This is a ‘historical’ perspective of Asterix across the decades, fairly entertaining and more so thanks to restoration work on the illustration. Fans will appreciate this, but it’s good enough to be enjoyed by even the casual reader.