Review by Roy Boyd

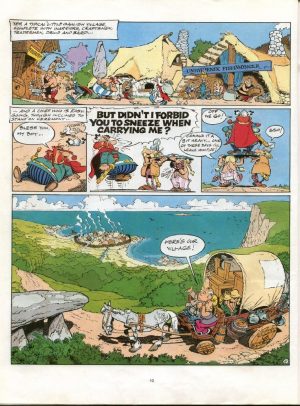

This 21st Asterix book by artist Albert Uderzo and writer René Goscinny, and is noteworthy as the first not to have been serialised beforehand in Pilote, but printed in its entirety as an album.

Julius Caesar, while handing out land to his retiring soldiers, exhibits a justifiably wicked sense of humour when he presents the deeds of a little Gaulish village to Tremensdelirius, a particularly inept soldier, who uses it to pay his bar-tab after getting plastered (or even more plastered – we never see him sober). The innkeeper, Orthopaedix, and his wife, Angina, pack all their worldly goods, and their lovely daughter, Zaza, into a caravan and head off for their new place on the coast.

Needless to say, their claim causes great hilarity amongst the Gauls of Asterix’s never-named village, though the kind souls do offer the visitors a place to stay, next door to Unhygienix the Fishmonger and his malodorous business. They open an inn, much to the dismay of Angina, who is miffed to discover they’ve left one inn only to open another, especially as she feels that the entire village is rightfully theirs.

Egged on by his domineering wife, Orthopaedix challenges Vitalstatistix for position of Chief, and the village descends into mayhem as people choose sides. Eventually the Romans are reluctantly involved, and prove to be the common enemy the villagers need to reunite, and there then ensues some delightful mayhem as the reconciled Gauls battle the Romans, with Obelix’s menhir-tossing skills more than a match for any catapult.

The creators had already explored conflict within the village in a handful of adventures, and would take an even less subtle look at politics in Asterix and the Great Divide, which features a village that’s literally split down the middle by a big ditch (a reference to the Berlin Wall). This book was produced at the time of the 1974 French presidential election, and that event looms large over proceedings. As always, contemporary references abound, whether it’s the long-dead actor that’s the basis for Orthopaedix, or the ‘Z’ (a reference to TV show Zorro) that Asterix slashes onto Tremensdelirius’s front during one of the Gaul’s rare swordfights.

Their treatment of women is not terribly enlightened, with much of the trouble in the story created by the wives of Tremensdelirius and Chief Vitalstatistix, pushy battle-axes both. Most of the women in the adventures of the indomitable Gaul and his well-built-but-definitely-not-fat companion either tended towards this type, or they were drop-dead gorgeous maidens. One could argue that the creators were mining a rich field already explored by, amongst others, Shakespeare in Macbeth.

As Goscinny and Uderzo had already proved on a number of occasions, Asterix and Obelix don’t even have to leave their village for hilarious adventures, and from a story perspective this has advantages in that the creators don’t have to introduce so many unfamiliar elements, and can instead develop the villagers as characters, most of whom are largely absent from the quest stories. It’s also possible that this book, unlike previous adventures, benefits from the lack of a weekly deadline, and the artwork is top-class: detailed, atmospheric and confidently executed, with a great deal to admire, especially in the battle scenes. And the writing, if one can excuse the somewhat male-chauvinist attitudes on display, is just as confident and assured. Excellent!