Review by Graham Johnstone

Artemisia Gentileschi is a feminist icon, driven by a life-changing trauma to make her name as painter. Working in established classical and biblical subjects, she painted empowered women, and has in turn been portrayed in plays, novels, feature films and documentaries, so a deserving subject for a graphic biography, or indeed two.

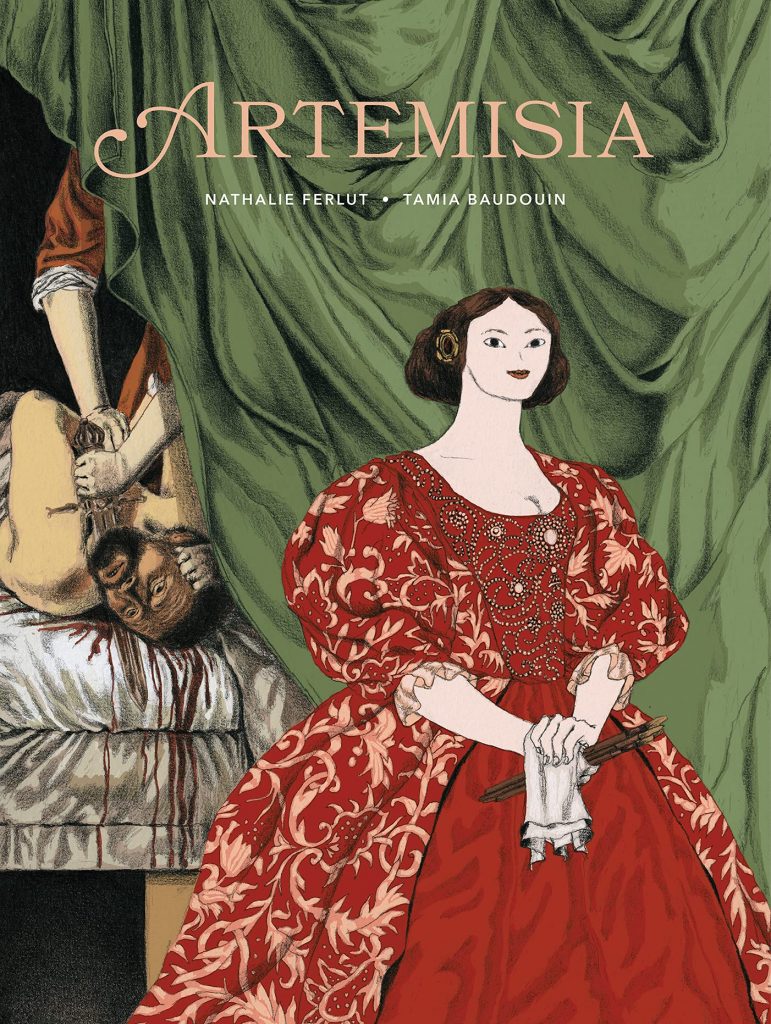

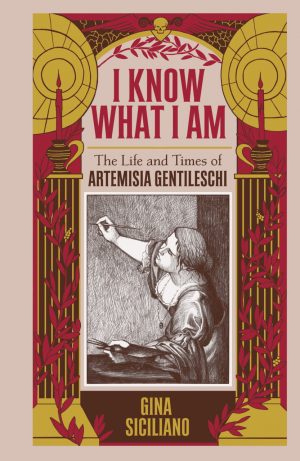

Artemisia was published in French in 2017, though 2019’s I Know What I Am by Gina Siciliano was first published in English. Some duplication is inevitable, but the books take very different approaches. I Know What I Am, true to its strap-line The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi, impressively establishes the context of 17th Century Rome, with a focus on the sexual politics and legal system that plays out in a major court case. It tends towards documentary, quoting heavily from historical records, and citing sources in extensive end-notes. Artemisia, is more a biopic, dramatising true events with fictionalised dialogue. Reflecting its title, Artemisia offers an appropriately concise account of the artist’s life in 100 colour pages, but does it do her justice?

Writer Nathalie Ferlut begins Artemisia’s story at thirteen years old, as self-appointed apprentice to her painter father Orazio. News is breaking through the artistic community of the conviction of ‘rock-star’ painter, Caravaggio. This neatly introduces key themes: the sins of artists tolerated for their talent, and the politics of the courtroom. This opening scene also establishes the pervasive sexual threat for women, worsened for Artemisia by her widowed father’s lax parenting and libertine associates. This is the core of Artemisia’s personal story, and Ferlut handles it deftly throughout, from painter Agostino Tassi’s engineering of private lessons for Artemisia (pictured), his rape of her, through justifications, promises and threats, to the neglect, complicity, and denial of those she trusted. It’s a historic event powerfully illuminated through modern understanding, notably of the methodologies of abuse. The resulting court case offers fascinating insights into the historic treatment of sex crime. It combines methods still in use, with others rightly consigned to history. The testing of Artemisia’s honesty in a method that could prevent her painting again is unforgettably poignant, demonstrating the powerful telling of this important story.

The depth of understanding Ferlut has for her subject matter impresses, but other elements are less assured. The dialogue often explains without finesse, though that may have been (literally) lost in translation. The telling of Artemisia’s story at one remove, helpfully reduces the burden of absolute veracity. However, this involves a frame story of Artemisia, her daughter Prudenzia, and their maid, Maria, on a coach-ride, necessitating contrivances to remove Artemisia, so letting Maria talk freely. The narration has a confusing segue from the opening authorial voice (“no muse sat on [Artemisia’s] cradle…”), to that of Prudenzia, and other captions, supposedly Maria telling the story, are sometimes jarringly literary. However, these niggles are far outweighed by the strengths.

Illustrator Tamia Boudouin impresses on her graphic novel début. Her characters are distinctive, and the story is well staged. Her settings convince, and her appealing freehand rendering integrates them well with her loosely expressive figures. Her sketchy pencils are bolstered by rich palettes, varying from sun-dappled exteriors, to the dramatic lighting pioneered by Caravaggio. Minimal faces and occasionally odd anatomy, hardly detract from the overall effect. Tamia Baudouin produced some beautiful pages with Ferlut on Dans La Forêt Des Lilas, so it’s hoped that will follow in English.

Artemisia is an important story powerfully told. It’s a more accessible introduction than, I Know What I Am, yet still delivers fresh and memorable insights into Artemisia’s life and times.