Review by Ian Keogh

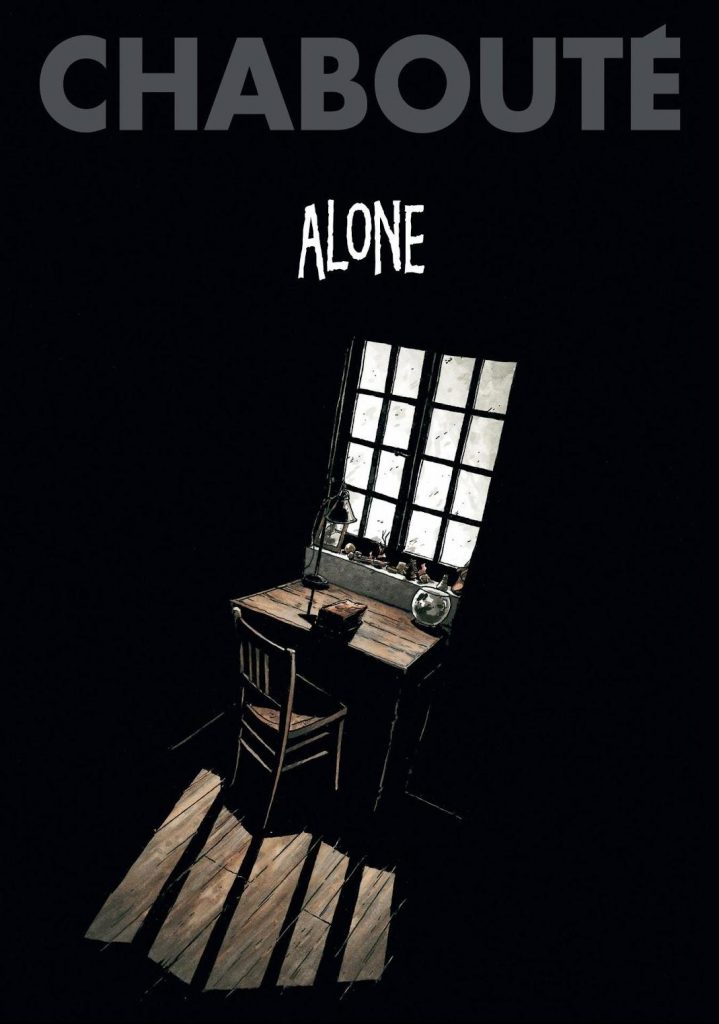

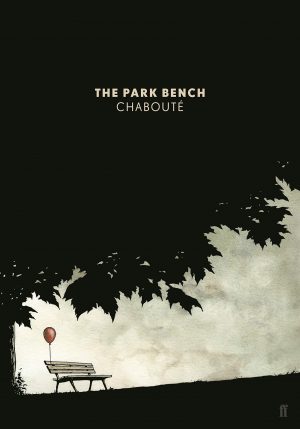

The title Alone has multiple meanings in Christophe Chabouté’s beautifully drawn and leisurely story. It’s the name given to the occupant of a lighthouse by the fisherman paid years before to deliver supplies there every week, and it’s the state of the occupant, who it’s said was born in the lighthouse and has never left the premises. Is he deformed, as claimed by the fisherman, who shows no curiosity as to the circumstances? Chabouté is in no hurry to confirm the rumour, only showing Alone via glimpses of his hands, or in silhouette over the first hundred pages, during which the same scenes of the lighthouse and surrounding sea are seen time and again. It certainly reinforces the intended sense of isolation.

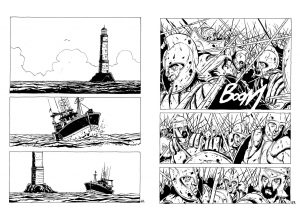

Over time, the story beginning with the dictionary definition of ‘imagination’ not only makes perfect sense, but comes to define what’s being read. As the right sample art shows, Chabouté’s story can lead anywhere. Because it’s not the point, it’s no spoiler to reveal the lighthouse does have an occupant, and they’re largely as described. Alone is enclosed, but surrounded by objects within the lighthouse, all recovered from the sea. There are few possessions by the standards of most homes, but more than enough to have formed a basis of education, and coupled with a daily stab into the dictionary to serve a life of learning and contemplation on a very simple level.

In one sense Chabouté’s art is also simple. He refers to the same scenes over and over again, and in terms of the actual illustrations includes little that’s not relevant to the overall story, yet he must draw the lighthouse over a hundred times. Each time it’s slightly different, according to the time of day, or the condition of the surrounding sea. Internally or externally every brick is lovingly detailed if the light is available, and Chabouté isn’t one for the short view. Internal scenes show how far up Alone must walk after every fishing trip.

To some it may seem the sheer number of pages and repetition isn’t necessary for the story being told. In one sense it isn’t, yet the reason is surely to have readers partially experience the pace of life as it is for Alone, and possibly how it was for Chabouté as he drew Alone. Very surprisingly, moments of absurdity are introduced from halfway as Alone comes across explanations in his dictionary for which he has no frame of reference.

Of course, having so thoroughly established Alone’s isolation, the natural narrative device is to disrupt it, which duly occurs, but in a clever way, Chabouté leading readers to presume one thing, when another actually happens. There is one unintentionally tragic moment, as a freshwater fish is released into the sea, leaving readers unsure if this an error of character or creator, yet it matches the prevailing mournful mood in presenting a life so few of us would want to live. Ultimately, though, it’s also uplifting and humane, Alone liberated by someone else who understands solitude. Soak in the atmosphere rather than rushing through, and this is one hell of a rewarding experience.