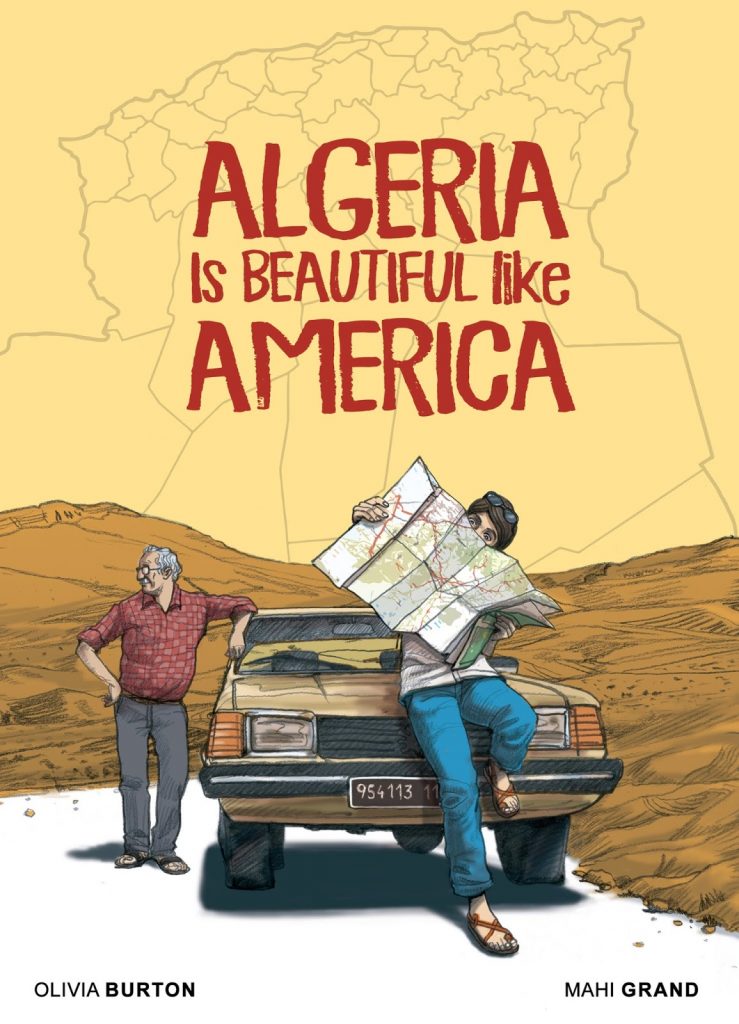

Review by Ian Keogh

During Algeria’s war of independence in the 1950s Olivia Burton’s grandparents moved to France, and she remembers idyllic summers spent with them, her grandmother constantly repeating that while Mediterranean France was nice, it wasn’t as nice as Algiers. Growing up in France, the history she learned about Algeria was at odds with the family version, and by her college years the discrepancies could no longer be denied, generating a conflicted and compromised view of her heritage.

Family history and background occupies the first third of the book. While many family members had talked about visiting Algeria, they never did, and when Burton, by then a French Professor, announced she was taking the trip no-one would accompany her. Instead she received dire warnings about primitive conditions and “The Arabs”.

It rapidly becomes apparent that Burton’s memories of family gatherings include many wholesale opinions to be frowned upon in the 21st century by a generation that hasn’t lived through war and oppression. It requires some delicacy on Burton’s part and that of French artist Mahi Grand to ensure that it doesn’t feed into anti-Arabic prejudice. Grand is a subtle artist who incorporates a lot of nice touches in what seems very straightforward picture referenced art, his nuances conveying what’s not highlighted in the text. An early surprise is a conversation regarding whose lives had been saved by others, illustrated by Grand via skeletons taking their place at the table alongside those who survived without that experience. Also effective is colour representation of Burton’s tourist photos in an otherwise black and white publication.

Like all good travelogues and reportage, Algeria is Beautiful supplies a series of jaw-dropping moments, some just funny such as an Algerian government grant for people to realise their dreams resulting in the majority buying a car, some interesting cultural interpretation and others disturbing. The company her family have arranged for Burton proves to be provocative as well as protective and when she finally reaches the Aurès region where her grandparents lived and her mother was born, it’s another eye-opening experience.

Burton began her trip burdened not with her own prejudice and fears, but those imposed on her by others, and what she discovers in Algeria rarely conforms with expectation, although the truth isn’t always palatable. Late on Burton uses a phrase about being on the wrong side of history, and that’s a gradual realisation finally underlined by her trip, where it’s rare that she has anything other than a warm welcome from people to whom her family’s questionable past is a distant country. It all makes for a very readable and personally engaging story, and unusually, reality provides a couple of surprises to provide a narratively satisfying ending.