Review by Frank Plowright

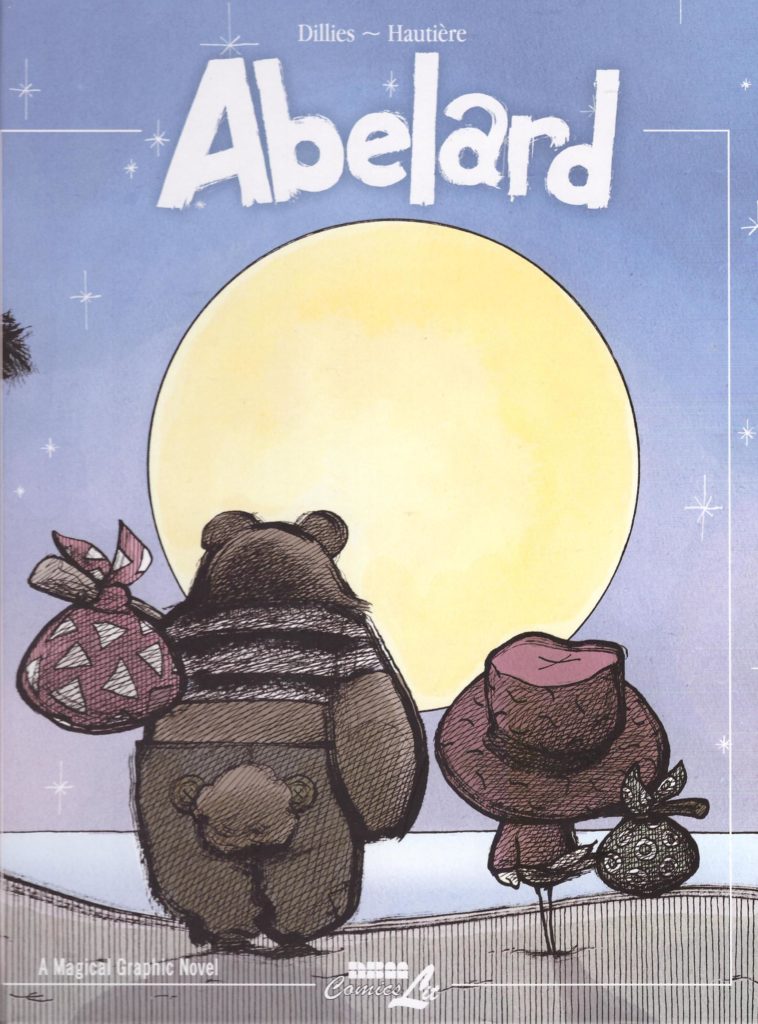

Abelard has always lived in the marsh. He’s got it good there, the country life being peaceful, but despite being told by people who’ve seen a bit of the world that there’s nowhere better to be found, Abelard has an itch that needs scratched. He’s particularly puzzled that there are so few women in the marsh, none of them young, so one day he takes his guitar and hat and sets off to see the wider world.

NBM’s other English translations of work by Renaud Dillies have been graphic novels he’s both written and drawn himself, and while the art has been fine, the writing has been inarticulate, introspective and distanced. Abelard has the benefit of writer Régis Hautière, whose career began early in the 21st century and has encompassed an imposing number of genres and projects. He provides a cohesion Dillies’ writing lacks, providing dialogue for Abelard to accompany the inherent sadness implied by the illustrations. It’s not clear from the credits if Hautière’s just scripting a plot from Dillies, or has additional input, but there’s a sustained nature to the narrative with natural introductions suggesting the latter. A particularly nice element is the magical realism of Abelard’s hat producing daily homilies to inspire and advise him as his journey continues.

There’s the usual charm to Dillies’ drawing, his design for Abelard not too far removed from Tweety Pie in the classic Warner Brothers cartoons, but when compared with the earlier Bubbles & Gondola there’s not as much background detail. Over the two volumes combined for the English edition there’s a deliberate policy of simplicity, but never at the cost of personality. On spreads where there’s not much variation, Abelard sitting and talking with the driver of a gypsy caravan being one example, the pages are dull, but for the most part the simplicity reflects Abelard’s character. Just as Mikhail’s pronunciation that there was nowhere better than the marsh was wrong-minded and ignored, Abelard learns to sift the opinions of others. He takes what works for him, and discards the remainder. His endearing innocence and optimism abides, though.

Having heard a flying machine has been invented, Abelard wants to reach America and see it, and if he can bump into Eppily again along the way, so much the better. Eventually, however, the focus shifts from Abelard to Gaston, very much close-minded when we meet him, and it’s ultimately his journey and his story.

Although the use of animal characters and the charm of the illustrations might suggest otherwise, as with Dillies’ other work this isn’t a book for children. There’s a constant existential questioning, and ultimately bleakness and tragedy guaranteed to break the heart. Appropriate advice from Abelard’s hat might be not to begin the journey if you’re not prepared to finish it.