Review by Ian Keogh

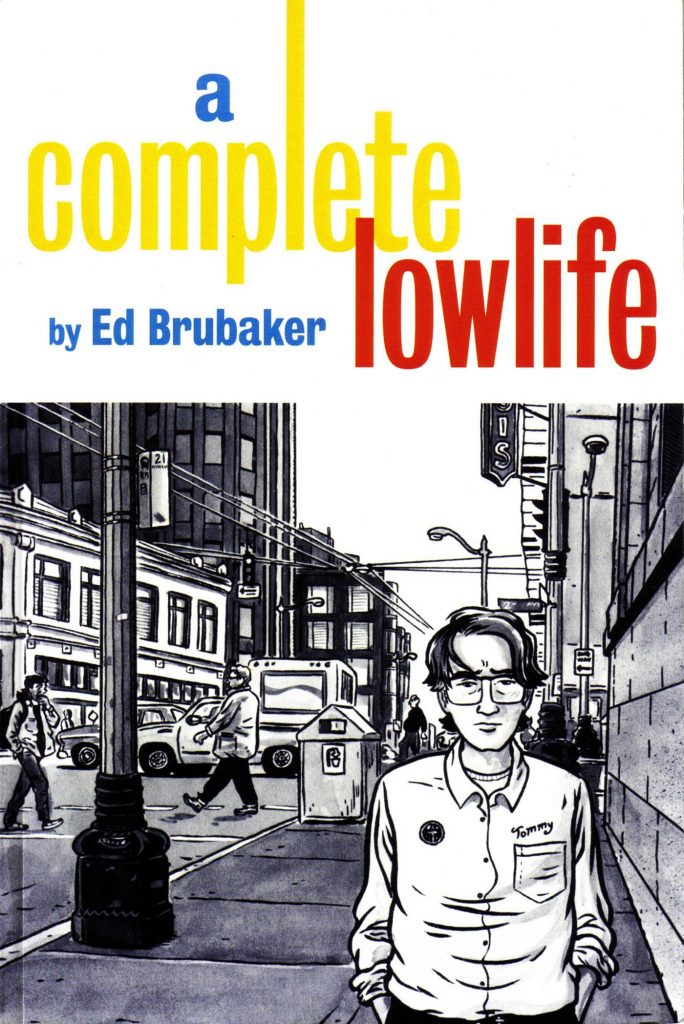

With his mastery of crime and action thriller material so complete, it’s startling to recall that Ed Brubaker’s comic career began in the early 1990s as a writer and artist producing autobiographical material, yet the proof is here. Presumably Brubaker sanctioned the publication, but it doesn’t paint his younger self in a very flattering light, and reading it through induces a gratitude that the more mature Brubaker is so skilled at other genres.

It’s immediately apparent that Brubaker is a tidy cartoonist, a skill he’s not followed up in public at least. His art resembles a slightly tighter version of Chester Brown’s work, with Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez also influences. While sticking primarily to a nine panel grid, there’s enough variety within the viewpoints to serve his recollections effectively, although it’s sometimes difficult to distinguish one character from another.

Despite being produced in the early 1990s with few years hindsight on his late 1980s to early 1990s experiences, Brubaker’s harsh on his slightly younger self, or at least his avatar, Tommy, although not without reason. Tommy is presented as self-pitying and self-absorbed with little consideration for others. He’ll steal from the eccentric shop owner who’s employed him out of pity, and in the collection’s best story he’s easily persuaded to take part in a robbery, despite initial misgivings. When it comes to relationships, though, Tommy’s a seething failure, and that’s the aspect that comes to dominate A Complete Lowlife. Brubaker has resequenced the stories from their original publication order, moving the material not overtly picking over his failed relationship to the front of the book, preceding an escalation of introspective strips.

These stories are far more personal than anecdotal, and come across as Brubaker raking over the coals, still unable to understand why he was unable to sustain a relationship with someone he loved. The answer, of course, is that more than one person is needed to sustain a relationship, something he surely knows, but never acknowledges here. It leaves attempts to present his feelings as unengaging, the distance between events and publication not providing understanding, but sustaining self-pity. While not a universal experience, broken relationships are hardly uncommon, and Brubaker’s dissection of his comes across as a plea for understanding. He addresses this in an interesting introduction, noting critics in the past have assumed he’s playing up Tommy for sympathy, and there’s a lack of a creative filter applied by creators of autobiographical material. The title alone is Brubaker’s damning indictment of his past, but there are autobiographical cartoonists presenting what they consider to be themselves at their best, yet who don’t come across that way to readers. Once any project is published, control over perception evaporates, and the way Tommy comes across may not be what Brubaker intended.

It’s ‘A Life of Crime’, the opening story, that points the way to Brubaker’s future narrative mastery. Tommy knows a planned robbery is fundamentally wrong and dangerous, and is a far more sympathetic figure as a loser possibly facing serious consequences than the earnest contemplator of lost love. The clever opening device of a police photograph initiates a tense curiosity that’s sustained until the unsentimental end.

Because Brubaker’s been so successful, Lowlife is an anomaly, faltering mis-steps toward something far better, but it would be interesting to see him draw a strip again.