Review by Frank Plowright

No One Else is a glimpse at a few months in the life of a Hawaiian household. The family home is now run by Charlene, a nurse barely able to cope with the demands of her job, being a carer for her elderly father and for a pre-teenage son who, quite naturally doesn’t really understand the pressures.

A thoughtful compact precision characterises R. Kikuo Johnson’s storytelling exemplified by the top page of sample art showing the passing of time and Charlene stockpiling problems by ignoring them. The exactness of the art contrasts the chaos of Charlene’s life, an ingenious use of Johnson’s style to fool readers into believing all is well. Also clever is that by presenting so much of the early stages from Charlene’s view convention would dictate that we’re supposed to sympathise with that view, when in fact it’s gradually revealed that Charlene is considerably flawed herself.

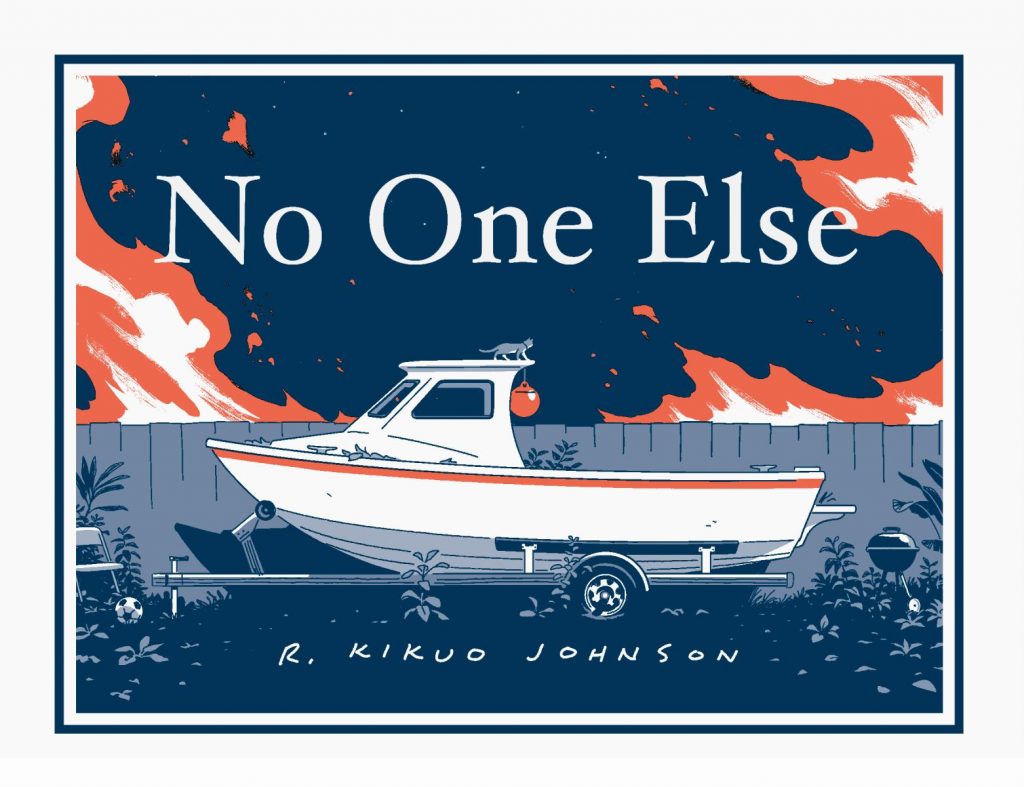

The narrative gradually switches to Charlene’s brother Robbie, who returns home to Hawaii after playing small gigs in Australia, becoming a permanent fixture on Charlene’s couch. He’s able to see she neglects her son Brandon and attempts to compensate, yet his own selfish nature results in lapses also. Everything coalesces into an extremely finely observed family portrait. Well chosen brief interludes in the past explain the resentments of the present, and how different personalities react differently to the same provocations and troubles. Casting a shadow over everything is the boat seen on the cover, reflecting the state of the household. Under other circumstances it would represent freedom, yet it’s decaying in a back yard.

Johnson maintains his commitment to emotional realism throughout, so with one possible exception, there’s no resorting to a narrative convenience to solve troubles. Even that possible exception late in the book is tidily allied with danger, and given an amusing coda where Johnson initially suggests one thing, yet reveals another.

In some instances when a creator deeply considers every panel the result is stilted, but Johnson avoids that trap via the sheer life and expressiveness of the art. Because he diligently uses full figure views this might not lock in, but the variety of expressions given to Charlene in times of stress are skilled and appropriate, while Robbie’s character is conveyed more by posture.

Everything gels perfectly for a naturalistic story in which we can understand each of the three main characters, who will be approached with varying degrees of sympathy likely to depend on each reader’s own definition of the balance between work, life and responsibility. Although a relatively slim read, Johnson’s early promise has matured into the fully rounded observational storyteller. The wry observation of No One Else is a cut above, and among 2021’s finest graphic novels.