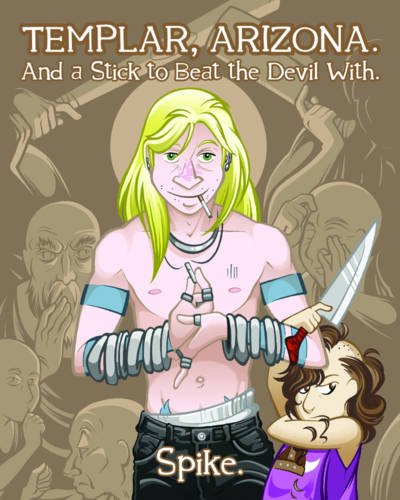

Review by Frank Plowright

Much of the focus in Templar, Arizona so far has been on Benjamin Kowalski. He’s genetically Asian, but adopted as a child, hence his name. We know he’s left home, and only wants to maintain contact with his therapist, but the opening pages here flash back to the departure.

They’re typical of the way Spike tells stories. She’ll offer portions and hints, but rarely comes out with a complete explanation, so in this instance we still don’t know why Ben left home, why he’s on medication or why he no longer wants contact with his parents. This might be assumed to be frustrating, but it’s not greatly as there’s always something else of interest arriving to distract our attention. In this case it’s the child from a neighbouring apartment appearing at Ben’s door having shaved her head.

So what kind of TV shows do our cast watch in Templar? We learn that early across some scenes highlighting how well Spike considers the voices of her cast. Speech patterns are individualised to the point that it’s possible to know whose dialogue is active even if they’re not in the picture. Those pictures still suffer from a very enclosed viewpoint, but are otherwise personality-rich cartooning.

As before, what we mainly have in And a Stick to Beat the Devil With is a lot of conversation, but ranging across such interesting topics. What constitutes good parenting is one. Does it tie in to Ben’s problems? We never find out, as there’s some seriously weird shit going on. A small dose was introduced in The Mob Goes Wild, but this is the full monty. Cults, girl fights, and a completely mad doctor with a hate on for the world are introduced, yet it all makes sense, perfect sense.

We met Sunny in the last volume, and he stars in the back-up strip taking a look at the Nile Cult who’ve been mentioned a couple of times. They base their lives, dress and worship around the equivalents from ancient Egypt. In some ways, although intended to be glimpses into elsewhere, the back-ups are more complicated than the lead strip, peppered with terms and references that may mean something, but are difficult to process. Maybe that’s the point.

By this third volume you’re either going to buy into what Spike is doing or not. It’s clever, but it’s also easy to see why some readers aren’t going to have the patience for the long run. Trouble Every Day is next.