Review by Frank Plowright

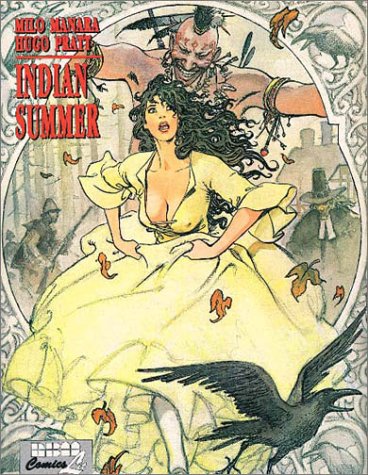

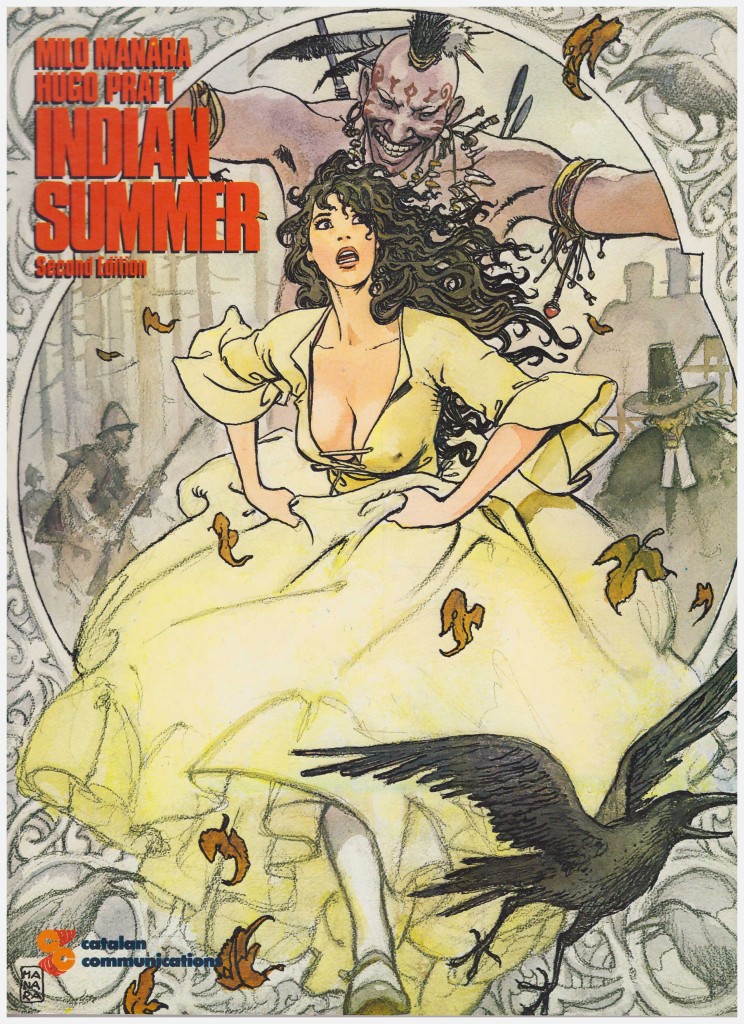

When first published in 1983 Indian Summer was a major event, uniting two giants of the European comic scene. Hugo Pratt’s work was acclaimed by intellectuals well beyond the world of comics, and his friend Milo Manara had featured him in a series of fables titled HP and Giuseppe Bergman. Manara had not yet developed the erotic niche that would cement a reputation, but his delicate line and consummate storytelling had long been refined, and Pratt was already the master of historical adventure.

Indian Summer is set in the early days of American colonisation, and an opening scene depicts the rape of a white woman by two native Americans. While leisurely, it’s not lingering, and telling that one of the young tribesmen has long blond hair, indicating his own lineage. They’re shot by Abner Lewis, one of a family exiled from the nearby settlement due to machinations of a hypocritical pastor.

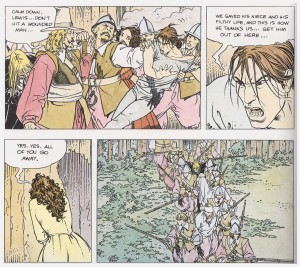

From that point a previously friendly relationship unravels, and hostilities escalate to an inevitable conclusion. Along the way sordid past deeds seep into the open, and in true old testament style, retribution is terrible indeed. The manner and pace at which the story unfolds is masterful, as is the choice to relate it via several voices, each with their own perspective. Historical accuracy is paramount. We’re in Nathanial Hawthorne territory as a woman bears a brand on her cheek, Puritanism is still rife, and relations between the native population and the recent arrivals still hasn’t descended into outright antagonism and persecution.

There is plenty about Indian Summer that’s more problematical in today’s climate than it would have been in 1983. We first run up against the European matter of fact attitude toward the depiction of sex, at which British and American sensibilities divide. The appalling attitude towards women as chattel is accurate for the times portrayed, but there’s a definite 50 Shades of Grey sensibility to the women of the cast, and the flaw is only presenting those women. It’s odd given the relative sensitivity with which the rape that sets the narrative in motion is handled.

Manara is at a peak here, inspired by the setting, by working with his friend, and still at that point interested in material beyond the erotic. His scenery and storytelling is sumptuous. So is his characterisation, with the true villain of the piece a stunning piece of sepulchral design displaying the rot within. His cast display by glance and posture, and, unusually for a writer, Pratt is content to let the art tell the story in several extended wordless sequences.

The volume concludes with a two page illustrated sequence in which Pratt lists the historical facts that influenced the story, although fabulist to the end, he can’t resist concluding with a fine mysterious flourish. Pratt and Manara would again collaborate a decade later with El Gaucho.

The translation used in this edition and the preceding Catalan-published version is slightly problematical, literal rather than idiomatic, and with an exceptionally odd use of ellipses. Kim Thompson’s re-working for volume one of Dark Horse’s Manara Library is far more satisfying.