Review by Frank Plowright

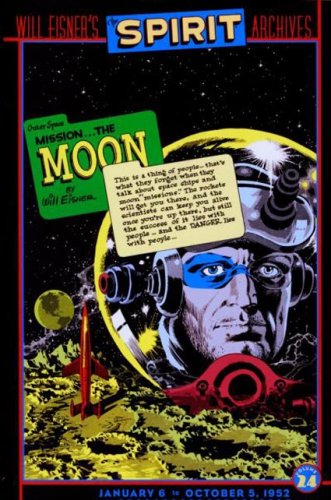

Wally Wood’s alluring cover welcomes us to the longest of the Spirit Archives, covering the final nine months of the Sunday newspaper insert from 1952. It’s also one of the most schizoid volumes, where a nicely drawn inventive story is followed by something lacking any spark. Many of the creators remain a matter for speculation, although, disappointingly, only Will Eisner’s name appears on strips in a book where his personal contribution was almost negligible.

The Grand Comics Database credits identify Jim Dixon as the artist responsible for impressively dark, moody art on some noir thrillers not far removed from Johnny Craig’s art of the time, yet a shortcoming of strips previously credited to him was a lack of ability with shade. That’s apparent on other strips seemingly drawn by him. Al Wenzel’s style is more cartoony, but neither exploit the opportunities provided by the plots as well as they could.

Based on his previous inventiveness, it’s apparent Jules Feiffer writes a fair amount of these stories, but possibly not everything credited to him at the GCD, as some are very ordinary. Those he writes to begin the year are darker than usual, featuring a suicide and the fictional death of Ellen Dolan. When on form, though, he supplies gems such as the tale of the Spirit trapped in a mine collapse and a French film pastiche in which the ludicrous French dialogue bears no relation to the translation. The GCD also theorises Klaus Nordling writes strips just too ordinary for him. In Spirit Archives 23 he may not have managed the whimsy and humour of the best Spirit stories, but his action strips are solidly plotted. A nice example is Commissioner Dolan reduced to a patrolman and the Spirit jailed.

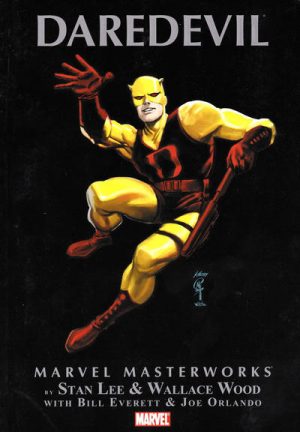

It’s a shame the inconsistency blights the better stories, but the material with the highest reputation at least ensures The Spirit departs with dignity. Eisner realised quality had plummeted, and he determined to save the feature by a change of direction and employing Wood’s first class artistic talent.

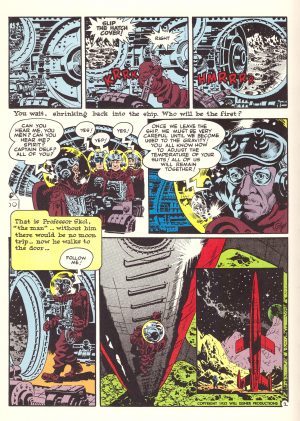

For all the good intentions, and the improvement on most of 1952’s other Spirit output, only the art ranks it alongside the best of The Spirit. In 1952 stories of man in space were yet to become commonplace on TV, and most accentuated fantastic adventure. Feiffer’s scripts concentrate on human drama, and are resolutely downbeat. That emphasis on more realistic human emotions is well enough handled, but far removed from the joyous whimsy associated with The Spirit, the change of tone too dramatic. Time has also dulled the wonder regarding a trip to the moon, so whereas the best of The Spirit is timeless, the attempt to produce something forward looking designates it a period piece now. Removing all context by publishing just the final two months continuity as The Outer Space Spirit provides a slightly better read.

Still shining, however, is Wood’s phenomenal rendering, known to comic readers at the time, but not the Spirit’s newspaper readers. His complex spacesuits, lunar landscapes and detailed machinery, all seen on the sample art, remain matters of wonder. Accommodating Wood’s schedule means the final few episodes are reduced to four pages, but what pages they are.

The final story, by Feiffer and Eisner, indicates The Spirit was intended to continue, but the next stories would only appear in the mid-1960s, collected in The Spirit Archives 26. It’s pleasing to see such a well crafted strip end on a high, but inconsistency plagues this collection.