Review by Ian Keogh

Fernando works in a Mexican hotel, saving his money carefully to fulfil his father’s dream of a better life for him. The trade off is that to provide for his family, Balthazar has to work away from them, now in New York, in the Windows on the World restaurant in the World Trade Center, which wasn’t a good place to be on September 11th 2001. His family see what happens on TV, but there’s no method of contacting him. It’s been an unheard of two weeks without hearing anything when Fernando’s mother sees Balthazar in news footage, proving he survived, so why hasn’t he been in contact? The only solution is that Fernando head to New York.

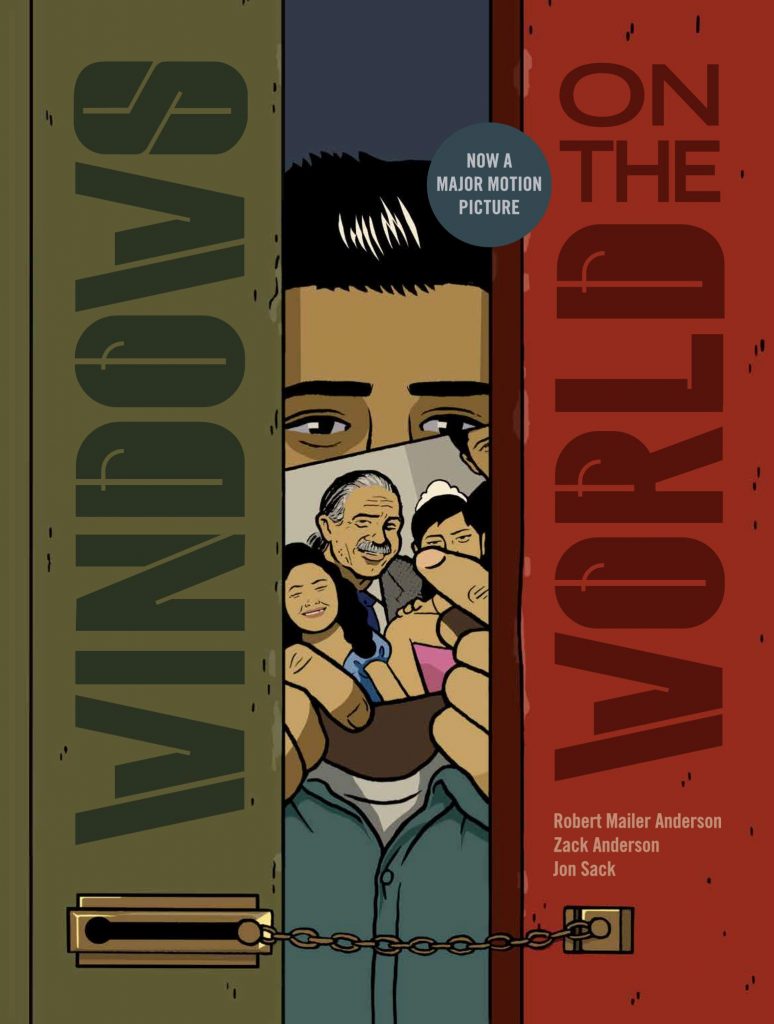

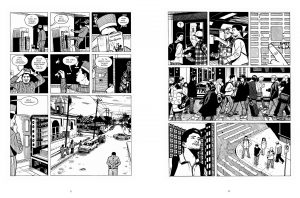

Published in 2020 when anti-immigrant sentiment was at its highest for decades, the writing team of Robert Mailer Anderson and Zack Anderson produce a story looking back to a time within living memory when the USA pulled together rather than apart. It seems to have been first conceived as a screenplay, not just because a film was also released in 2020, but because writers new to comics consider the visual possibilities more than might be expected. The writers also have a leisurely style, again evoking cinematic storytelling, obvious during Fernando’s six page bus journey across the USA. Jon Sack sells all this comfortably, his attention to detail both in surroundings and expression compensating for his not being the best at conveying movement. The visual richness and Sack’s work ethic is displayed by the effort put into a single page showing a section of New York from above. It covers a few blocks around the Empire State Building, and the only story purpose is to establish Fernando locating an address. That visual density is apparent in the contrasting sample pages of Fernando walking at home, and in New York. Jaime Hernandez is a definite influence, and while Sack isn’t yet as skilful, he’s an artist to admire and watch.

Windows on the World takes the title of the restaurant and uses it in microcosm as it applies to Fernando, the windows he sees. A more literal reading comes later, but the atmospheric interpretation is the creative priority. There’s rarely a page where Fernando isn’t featured, and this thorough immersion in wherever his surroundings are at the time gives an understanding of what he experiences, while that informs who he is. The locations also cement his father, about whom Fernando learns more as he searches. Fernando’s diligent, smart and thorough, but will that be enough to find his father and to survive in a hostile city? The answer is poignant and ultimately terrifying as Fernando meets someone who survived the Twin Towers disaster. Some brief, but unironic mythologising of New York in a scene toward the end is unfortunate in the face of the reality so diligently laid out, but that’s a minor glitch in a moving and thoughtful rite of passage.