Review by Karl Verhoven

Little Nemo in Slumberland was among the earliest newspaper strips, dating from the first decade of the 19th century, yet such was the skill and imagination applied by creator Winsor McCay, it’s still considered a genre pinnacle. That being the case, any creator generating a revival is going to be well aware of the standards against which their work will be judged, the artist moreso than the writer. There’s no pretending Gabriel Rodriguez matches McCay’s prodigious talent, but he’s in no way disgraced.

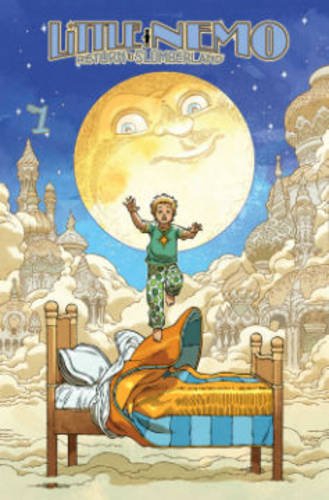

For those unfamiliar with the original strip, every night when he fell asleep the young lad Nemo would be transported to Slumberland for an incredible adventure, initially complete in a single oversized portrait page, with later adventures continued. Each strip ended with Nemo waking up disoriented in his own bed. Puzzlingly, in complete contrast to the expansive nature of McCay’s work, IDW have published this not even at standard trade size, but as a pocket book.

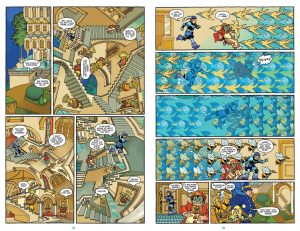

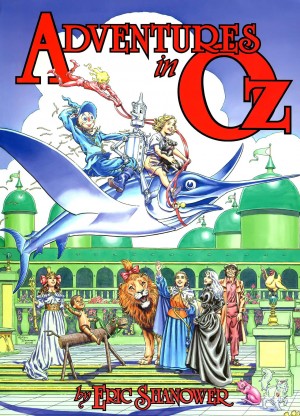

Eric Shanower’s plot substitutes the early 21st century for the original era, but as barely any of the original strip occurred on Earth, that’s no great change, and nor is there much change in Slumberland, where almost all is as it was a century before. King Morpheus still rules, the Princess needs a playmate, and Rodriguez has McCay’s designs to fall back on for the sumptuous court and courtiers. A new playmate is found, but is reluctant. “I don’t play with girls! I don’t like this dream”, protests James Nemo Summerton, his middle name derived from a cartoon fish. He soon comes to appreciate the wonder of Slumberland, and so do we as Shanower’s imagination is channelled by Rodriguez to supply wonderful, eye-opening sequences. McCay’s strip was presented to children who had no cinema or TV and barely travelled. If they did it was unlikely to be outside North America, yet with all the advances, Shanower and Rodriguez still produce visions to wonder at and stimulate the imagination. Theirs is a more linear story, but the priority is still visual splendour, and page after page is breathtaking. Rodriguez keeps spectacle at the forefront, Nelson Dániel’s bright colours creating a constantly vivid landscape, and one creative device follows another.

Two differences separate this version and McCay’s, this lacking the racist caricature that constituted one of the Princess’ other playmates, all the mischievous tendencies now residing in Flip. Otherwise while the likes of Doctor Pill and the Candy Kid put in an appearance, there’s no necessity to know they were McCay’s designs. The other difference is James is a modern kid, unimpressed by the stuffiness and formality that accompanies Slumberland’s visual magnificence. It’s the desire to avoid it that sets him off on his journey of discovery.

Return to Slumberland straddled two worlds successfully enough to earn an Eisner Award nomination, although that it stands alone probably speaks to how it was received by the 21st century equivalents of McCay’s original audience. It is however, a beautiful looking story, and one it could be imagined would please McCay.