Review by Frank Plowright

Spoilers in review

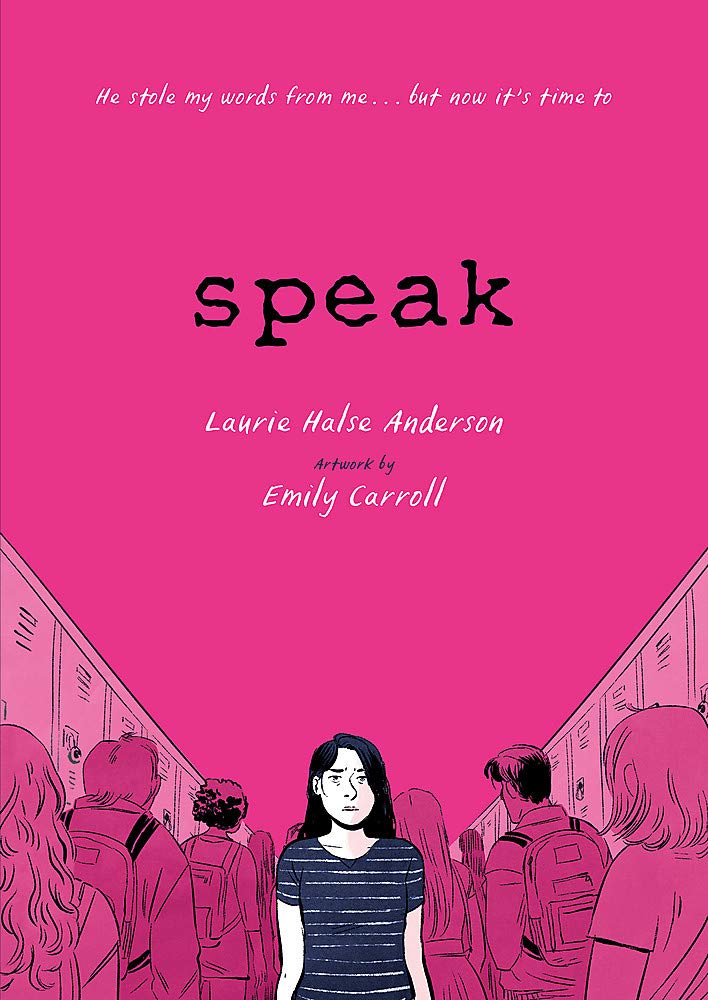

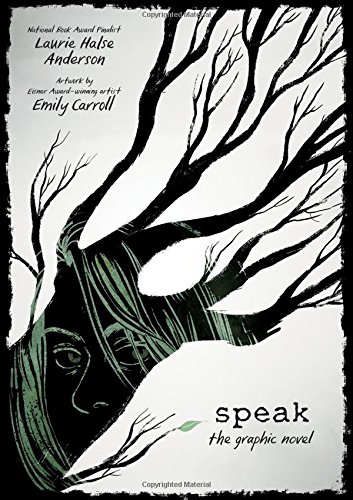

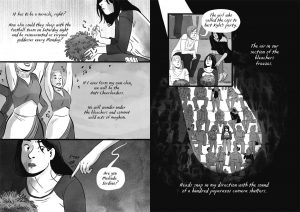

Emily Carroll’s adaptation of Laurie Halse Anderson’s 1999 young adult novel opens by establishing circumstances as normal as possible, the first day at high school in a small Midwest town, while simultaneously pointing out the contradictions and shredding the truth from them. Melinda has ex-friends, is tormented, withdrawn, and doesn’t want to engage at any level. We learn that she called the police to a party, which is why she’s despised, yet not immediately why she did that. Carroll breaks down the indignities and torments into two to four page titled chapters, as Melinda copes by biting hard on her lips as she represses what she needs to say.

It’s unlikely people will arrive at this adaptation without knowing about Speak and what’s troubling Melinda, although if that is the case then Carroll maintains the tension well. Melinda’s narrative creates a likeable girl with wit and creativity, exactly the type of person the school system ought to help flourish, yet it’s a system designed to ignore how lost she is. Her parents are only staying together because they believe it’s the right thing to do for her, so their relationship is fractious, and besides, they have their troubles, so she feels she can’t load hers onto them. If that isn’t bad enough she regularly comes into contact with the boy who raped her.

The title serves two purposes. There’s a nod to Maya Angelou’s autobiographical books, referenced by Melinda, a key part of Angelou’s experiences being an inability to speak, and it’s the reader’s scream at Melinda, as she spirals ever downward. In addition to Angelou, her experiences are reflected in the lives of others like The Scarlet Letter’s Hester Prynne and an art teacher whose creativity is blocked, while the significance of her art project is superbly revealed. Watching Melinda sink doesn’t make for a comfortable read. Were that the case it would defeat the purpose, but there are necessary lighter moments breaking up Melinda’s torment. However, even the resolution, as good as it is, is dark.

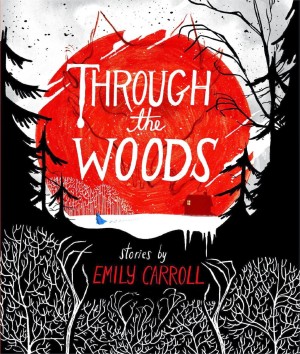

This is Halse’s story in Carroll’s care, and she’s produced a first class adaptation, sensitive and direct in separating right from wrong. It should be required reading, yet there are people determined that you don’t read it. Between 2000 and 2009 Speak numbered among the hundred most challenged books in the USA by people militating to remove it from schools or library shelves. Astonishingly, one critic described the horrifying rape, the book’s central incident, as soft pornography. It seems many still feel speaking up about sexual assaults is more offensive than them occurring in the first place, which is the point Speak addresses. Current estimates are that 30 US women per 100,000 will be raped, yet to some it’s more important that teenagers are protected from a book dealing with the subject compassionately. This is the nutty world we live in.