Review by Frank Plowright

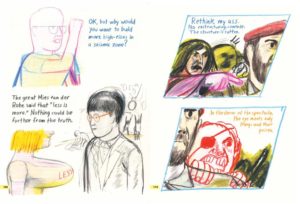

An increasingly absurdist quality manifests in Viken Berberian’s story of a young architect whose love of concrete transcends rational explanation. Frunz was encouraged to be a precocious overachiever from infancy by his mother, and studied in Paris, but was drawn to his father’s homeland of Armenia when offered a position at the State University’s Concrete Masonry Institute. His background is told as he escorts students around the Armenian capital Yerevan, delighting in the concrete wrecking balls demolishing the old around them.

Berberian throws open the political aspects of architecture and through Frunz discusses its purity. For Frunz the concrete structure is all, the symbolism of greater importance than the practicality. He’s a man of influence who wants to create places conforming to his narrow view of beauty, but the concerns of application are secondary, and he spurns protest with empty platitudes, Berberian echoing the Soviet era Frunz wants to demolish. Form and function are twin gods, but unfortunately, for him at least, his vision is interrupted by the will of the people in storming the presidential palace. Because his views are expounded at length from a position of supposed authority, it takes some time to realise Berberian intends Frunz as a satirical creation, a representation of the artist unable to see reality in front of them.

Just as Frunz rails against ornate structure, so Yann Kebbi’s art is deliberately distanced from traditional comic art, dispensing with panel enclosure and everything outlined in black. However, again reflecting Frunz, Kebbi’s lack of respect for form doesn’t imply he’s replacing it with something better. For long periods his art isn’t storytelling, but a succession of illustrations, many with a two-dimensional flatness, again echoing Frunz. Kebbi applies the same aesthetic to the extended pages of Frunz’s sketchbook. Symbolism abounds, whether it be sexual metaphors centred on the increasingly large breasts on a student Frunz escorts around Yerevan, or the constant restructuring represented by the wrecking balls. At first it seems Kebbi’s also an impatient artist, some pages just dashed off, until it drops into place that it’s further symbolism. The places given weight are those Frunz engages with, while all else is meaningless, therefore not fully realised. It’s clever, but risks passing people by.

The Structure is Rotten, Comrade is very funny in places, such as Frunz attempting to placate an angry mob, it being beyond his comprehension that they’re unable to see the value of stools designed by Alvar Aalto. The objectified repetition of the student with the large breasts pays off when she crosses out the word ‘less’ on her t-shirt slogan so it reads ‘more is more’, in keeping with Frunz’s stridently ridiculous views. It’s funny, but practically her only purpose, which is a little behind the times. However, the repetitive imagery over the first half of the story is extremely off-putting, and for what amounts to a farcical rise and fall plot, a graphic novel equivalent of Dario Fo’s theatre absurdism, too long is taken to say too little.