Review by Frank Plowright

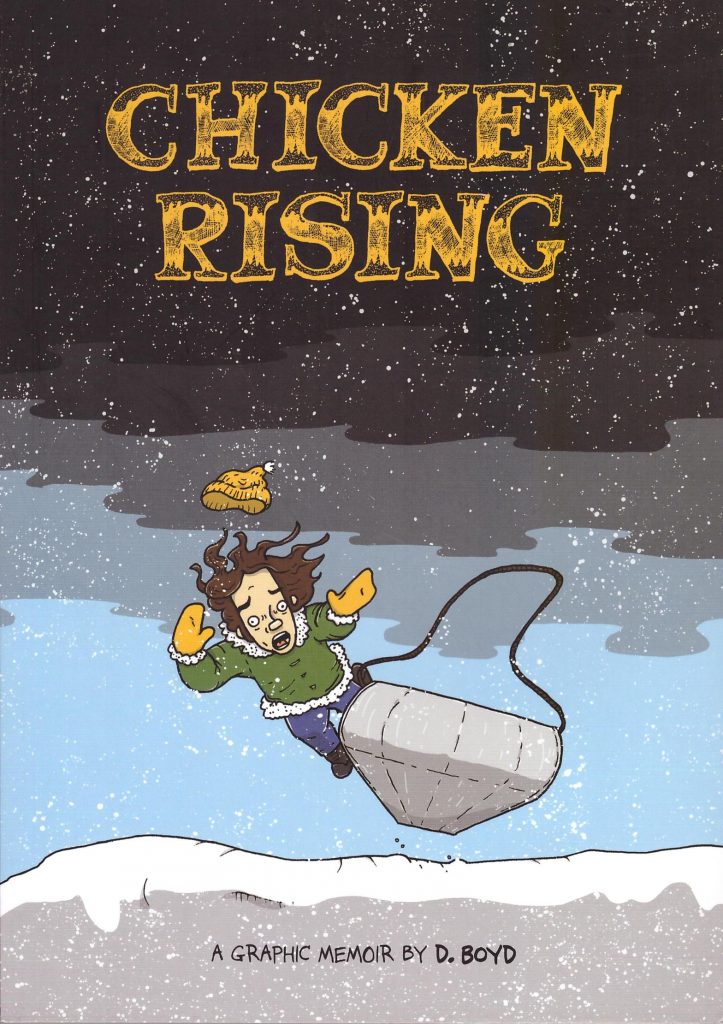

D. Boyd has selected a remarkable author photo to accompany Chicken Rising. Placed in the back after we’ve read her childhood memoir, it shows the adult author looking incredibly sad, almost on the verge of tears, glancing to our left back at the content just finished. Tears may be unrestricted after reading about a child relentlessly put down, bullied and by current standards abused by parents who believed praise somehow weakens a child instead of encouraging them.

Boyd presents her past in a series of one to three page segments starting in 1970 when the family moved to a small New Brunswick town to open a chicken diner. She was a withdrawn, but excellent student whose maths was weak, yet reports noting this would generate scolding, and when she struggled to improve to the point of achieving 99% on a test she was told off for not reaching 100%. Occasional guilt and an over-protective attitude on her mother’s part substitutes for encouragement, while her father’s not interested in any of her activities or achievements on the basis that they’re not sport, and any plea for help generates a response to toughen up. There’s no comfort at school either, where a one size fits all education system failed Boyd as it failed so many other sensitive, artistic children. She remains a solitary child who has difficulty making friends, with her mother judgemental about those she does make. That some school torments feature children unable to explain why they do something when challenged, makes the experience no less unpleasant at the time.

The cartooning is neat, lively, detailed and emotionally strong, Boyd able to convey exactly how her younger self felt at any given moment with an appropriate illustration. However, there is an off-putting problem. Late on in the book other children are seen making fun of Boyd’s nose, a family legacy, and she draws herself and every member of her family with a peculiar oblong at the end of her nose. Humans in Disney comics were always drawn with strange black splodges for noses, and this is even more distracting, as if people have sweets stuck to the end of their noses. It doesn’t work.

Partly because there’s no real closure, Chicken Rising is profoundly uncomfortable reading, although presumably cathartic for Boyd. Her mother occasionally apologies for not believing her daughter, but rapidly reverts to usual behaviour, and an admission in April 1977 that she’s become her own mother is too little too late for most readers, never mind Boyd herself, although presented as at least some understanding with tears and a hug. The matter of fact presentation throughout is very effective, Boyd never intruding with explanatory captions beyond dates, letting readers pick up the emotional subtext themselves. A strange ending has the Boyd of summer 1977 expressing her desire to become a psychiatrist. It’s weak, and Chicken Rising cries out for a few pages summarising the years beyond 1977, a list of achievements. Perhaps Boyd’s feeling is that there was no comforting closure for her, so why should readers get that? Otherwise this is heartfelt and moving, constantly prompting the desire to give a lost child the comforting hugs denied her at the time.