Review by Frank Plowright

To anyone with knowledge of cinema history, Victor Santos using the title of what’s widely reckoned among the greatest movies ever made is an indication of setting the expectational bar for his work very high. As in the film, the opening setting is the Rashomon Gate in feudal Japan, with a murder taking place on a rainy night, but Santos is more influenced by the original Ryunosuke Akutagawa stories adapted for the film. He seizes on the idea of contradictory and self-serving accounts of the murder by people claiming to have seen it occur, either taking responsibility or as witnesses, and from the person who discovered the body and someone who saw the victim briefly beforehand. To cut through the contradiction Santos introduces a character of his own devising, Commissioner Heigo Kobiyashi, who continues into a second investigation.

At the heart of the opening story is whether anyone can be truly objective, and Santos expands on the original via a scene where the victim is additionally summoned by a medium to register their account. A neat ending for readers provides the conclusion that eludes Kobiyahsi. The second story is connected to the first, structurally by featuring a magistrate now familiar, and thematically via Kobiyashi again having to sift the truth from conflicting accounts, at least to begin with. It’s based on another famous Akutagawa story, The 47 Ronin, Santos again making some changes to accommodate Kobiyashi. It eventually broadens to a siege, but far more so than the first story an appreciation of Japanese protocol and honour is needed. Santos has presumably researched, but to anyone not versed in the niceties, the clash of politics and investigation induces some confusion.

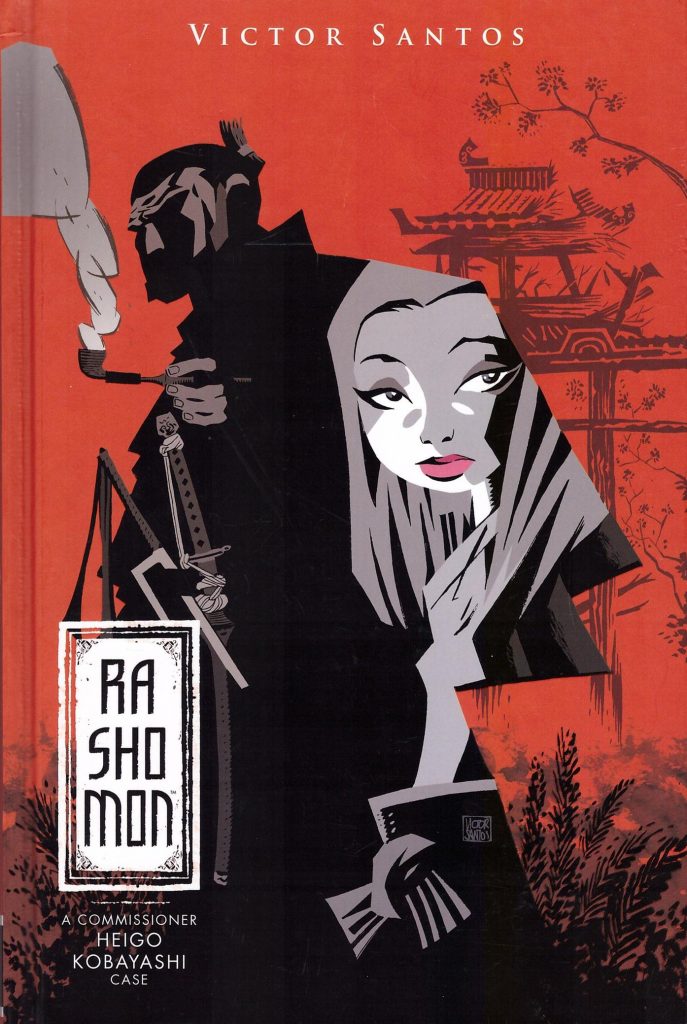

Santos is a superbly evocative artist. In terms of the stark light and shadow for his black and white pages Frank Miller’s Sin City is an obvious influence, but Santos also works in vivid colour, sometimes as decoration and sometimes as narrative device, such as distinguishing testimonies in the opening piece. When using a full page featuring an alluring woman the composition also echoes Japanese illustrations, but with Miller’s stark lighting style. It’s very effective. So are the pages where Santos drops back into simple linework with a colour overlay, and what are almost cartoon action spreads toward the end.

The value of both stories is in the art, pages that can be stared at lovingly, but which are also the downfall. Technically it’s excellent, but without emotional connection to the victims or the suspects, resulting in an absence of tension. Crucially, it’s also lacking with regard to Kobiyashi, presumably devised to compensate, yet rather mechanical. Without the tension Rashomon is a beautifully drawn intellectual exercise.