Review by Jamie McNeil

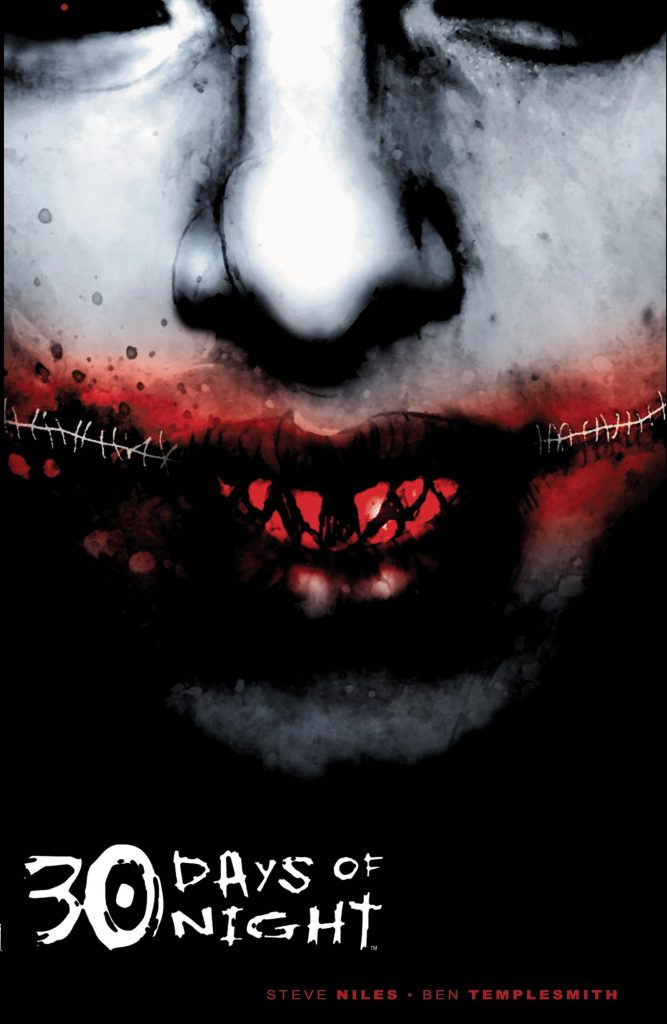

In 2002 the horror comics genre wasn’t exactly lighting up the world when little-known writer Steve Niles and fresh-faced artist Ben Templesmith emerged onto the scene with 30 Days of Night. It was a simple re-invention of vampire lore, featuring macabre yet startling art that helped herald in a horror revival.

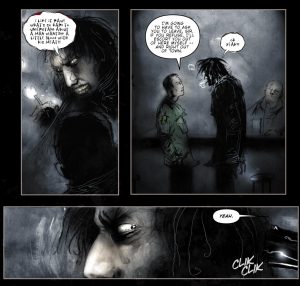

The town of Barrow, Alaska is the most northerly situated community on the American continent. Nothing more than a few buildings in a frozen wasteland, the summer months enjoy perpetual sunlight but for thirty days over November and December, Barrow is shrouded in darkness. Usually the town’s husband and wife Sheriffs Eben and Stella Olemaun cherish the last sunset for the month together, but this year Eben isn’t enjoying the moment. Barrow is experiencing a mysterious crime spree, the latest of which is a scorched pile of stolen cellular phones. He can’t shake a bad feeling and when they pick up a drifter with a taste for raw meat and whiskey, things go horribly sour. The drifter’s ravings of evil come to Barrow are realised when horrors from myth and nightmare descend. With sunlight their only weakness the inhabitants are a buffet of human flesh for vampires. Now the Olemauns lead a group fighting for survival until daylight returns or help arrives. They may see neither.

Niles’s idea for 30 Days of Night is so simple horror writers around the globe were probably smacking their foreheads crying “Doh!” when they first read it. A genuine geographical location where darkness lasts longer than twelve hours is a perfect setting for revising the vampire mythos. It is a truly terrifying concept that plays off our deepest primordial fears, allowing Niles to stretch out the tension and change the rule-book on vampire behaviour. No baroque settings or hormonal love triangles, just scary-as-hell pee your pants monsters with limited weaknesses who all the time need to gorge themselves. Niles paces his plot, building up to the relentless misery rather than diving straight into it. His protagonists can reach conclusions without explanation largely. Because it was intended to be a one-off, there are points where for the sake of time conclusions are jumped to rather than explained in detail, but he still manages to jangle the nerves.

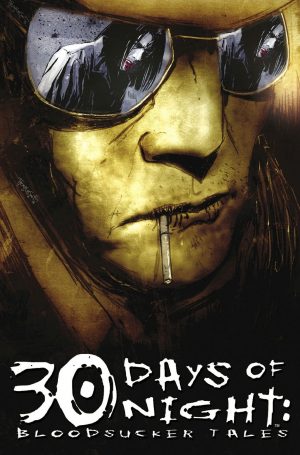

Templesmith’s unusually loose art is a driving factor to the initial success. The pages are swathed in eerie shades of watercolour to emulate the darkness with the cast barely lit. The contrast catches the eye and when bright colours are used, the result is beautiful and sinister. This is early in Templesmith’s career and he’s already showing a talent for grasping the reader’s attention and amplifying the terror with his visuals. Rows of glinting sharp fangs in a shadowed face and gore splattered across the page only play on the natural fear of the dark unknown. While the art facilitates the story well, his relative inexperience results in a cast that lacks definition, making it hard to identify them. Still you can’t deny that his style delivers.

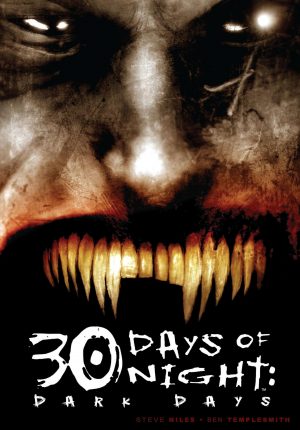

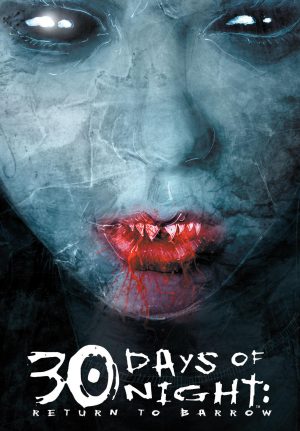

30 Days of Night is drenched with despair. Noir-like in outlook it takes horror back to basics, kick-starting a genre revival, not to mention garnering the fledgling IDW Publishing attention. Time shows up the flaws but, despite the concept now being over-used, it still works. Niles, Templesmith and IDW found themselves with a hit that readers were clamouring for. Along with a film, sequels would follow the first of which is 30 Days of Night: Dark Days. Both books can be found in the 30 Days of Night Omnibus.