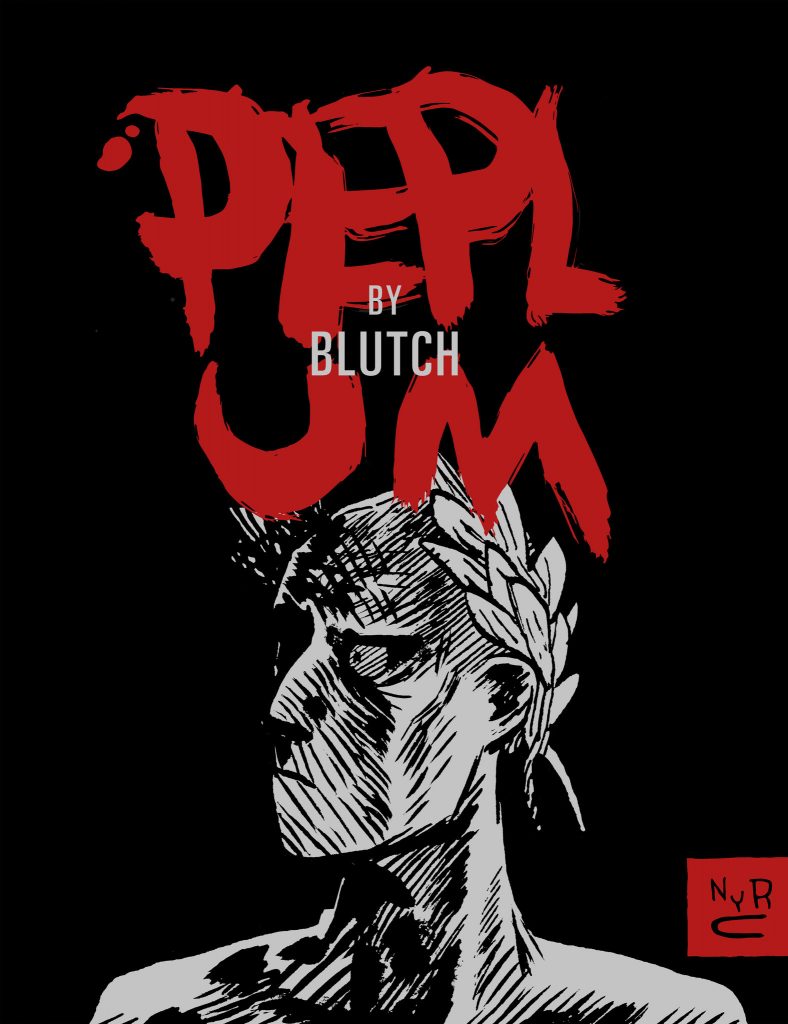

Review by Ian Keogh

Translator Edward Gauvin presents an enlightening introduction to Peplum, contextualising it as the result of Blutch in 1997 wanting to step away from both the traditional Western and crime serials he’d been working on, to create something stripped down and fresher. He felt antiquity held the answer and took Satirycon as an inspiration, but by the time he’d finished something very different had emerged. The story is an apt metaphorical reconstruction of his own transformation, that from artist for hire to visionary creator.

Peplum is very staged, indicated from a sequence in the opening chapter which quotes Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar at length, the relevance being that a plea for mercy for an exile we’ve already met, Publius Cimber, in Shakespeare prompts Caesar’s death. Cimber doesn’t long outlive him, his place taken by an imposter in whose company he’d retrieved a woman frozen in ice. Her beauty can be seen, but she remains encased, the life to which the men believe she’ll return being one of inspiration. The imposter embarks on a wild and violent tour of the excess and casual brutality of the Roman Empire, possessed by an obsessive addiction, and holding to an ideal rather than succumbing willingly to less than perfect alternatives. When he believes a living substitute has been found to his goddess, the thought of betrayal institutes performance anxiety

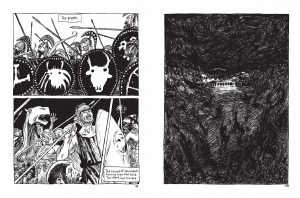

The imposter engages in all manner of appalling activities, yet Blutch presents them devoid of judgement or comment, and applies the same detached manner to conventional storytelling. Leaps are taken, avoiding what in other dramas would be the scenes authors build toward, the often florid dialogue at times appears designed to point toward the art as method of more effectively presenting the story, and make of the epilogue what you will. This is all, perhaps, over-analysing. Blutch himself is quoted in the introduction claiming he doesn’t intended to be seen as a difficult author, and that his priority is always action. In Peplum it’s frenzied and primal, the departure back to antiquity stripping away the veneer of civilisation far more efficiently. Blutch’s art is a scratchy rush, yet perfectly composed and surprisingly switching style if he feels a scene demands it.

A career changing graphic novel for Blutch, Peplum won’t be to all tastes. Anyone wanting an accepted narrative structure, with explanation and resolution is pre-ordained to disappointment. A thorough immersion in the spirit of the moment, however, provides considerable rewards.