Review by Ian Keogh

He was active for just over three months in 1888, yet Jack the Ripper’s murderous career continues to fascinate, a consequence of both the brevity of his activities, their shocking nature and that he was never brought to book for his crimes. In researching From Hell Alan Moore consulted a wealth of already published material to present his own conclusions as to culpability and purpose. The result is the densest of his comics work, presented in the ancient Chinese literary tradition of relating known events in a fictional setting.

It’s far more, however, as what may have been sold as mystery in its direct presentation of Jack the Ripper actually contains none. There’s a step by step progression instead, laying out reasoning, misogyny and procedure, and unlike some graphic novels, this is a true collaboration. The 44 pages of notes in the back may be Moore’s work, but the precision of Eddie Campbell’s locations and his recording of nineteenth century social conditions indicate serious time spent on research also. For both creators this isn’t just on the murders themselves, but on the lives of the participants, explored in considerable detail, and the declining British Empire. The devil is in that detail, and it’s this diligence that ensures From Hell remains a compelling slab of historical drama irrespective of Moore’s conclusions as to who Jack the Ripper was. Freemasonary is integral to events, as is architecture and a torrent of ideas, speculations and hypotheses. In microcosm the fourth chapter best represents From Hell. It’s a tour of London by coach as experimental Victorian surgeon William Gull expounds upon his learning and his theories, with a coachman his captive audience and sounding block. Even in isolation it’s an immense piece of work, dense and puzzling, yet the key to unlocking the remainder of the book.

All the talk of depth and ideas perhaps underestimates how well the primary members of the cast are constructed from biographical wisps and scraps. The unhinged Gull and his master plan, the dour Inspector Abbeline, the crumbling Nettley and even lesser characters such as the ultimately pitiful Walter Sickert are all memorable.

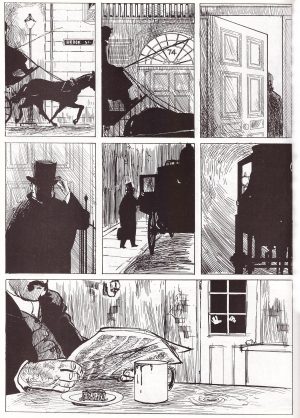

Campbell’s art has always been loose and expressive, but here he filters in influences from Victorian era illustrators, particularly via creating an illusion of solidity on clothing via multiple parallel lines. While the style had been recognisably Campbell’s for years, its scratchy nature is ideally suited to contrasting the perception of Victorian order and propriety. Indeed, when opulence is required, he resorts to grey wash, underlining the partition. To single out one effective recurring piece of imagery, the horse drawn coach touring the underbelly of late Victorian London in near complete darkness is tidy foreshadowing. It’s sinister, yet simultaneously on the cusp of extinction.

Not all aspects of From Hell will work for all people. Moore’s exhaustive research led to the minor intrusion of anachronistic elements, which appear fanciful and somehow strike a false tone, as do some of the celebrity cameos, that of a young Aleister Crowley for one, but this is nitpicking with regard to such an immense achievement. Moore’s copious chatty notes are enlightening, but his skill is such that his story can be read and understood without them. There’s furher a sly epilogue beyond the notes, in which Moore traces the history of Ripper literature and its reductive nature.

Brutal, rambling, fearsomely intelligent and endlessly fascinating, From Hell sits comfortably among the greatest graphic novels. If you’ve not read it you should, and if you have, read it again. You’ll be surprised how much you’ve missed.