Review by Ian Keogh

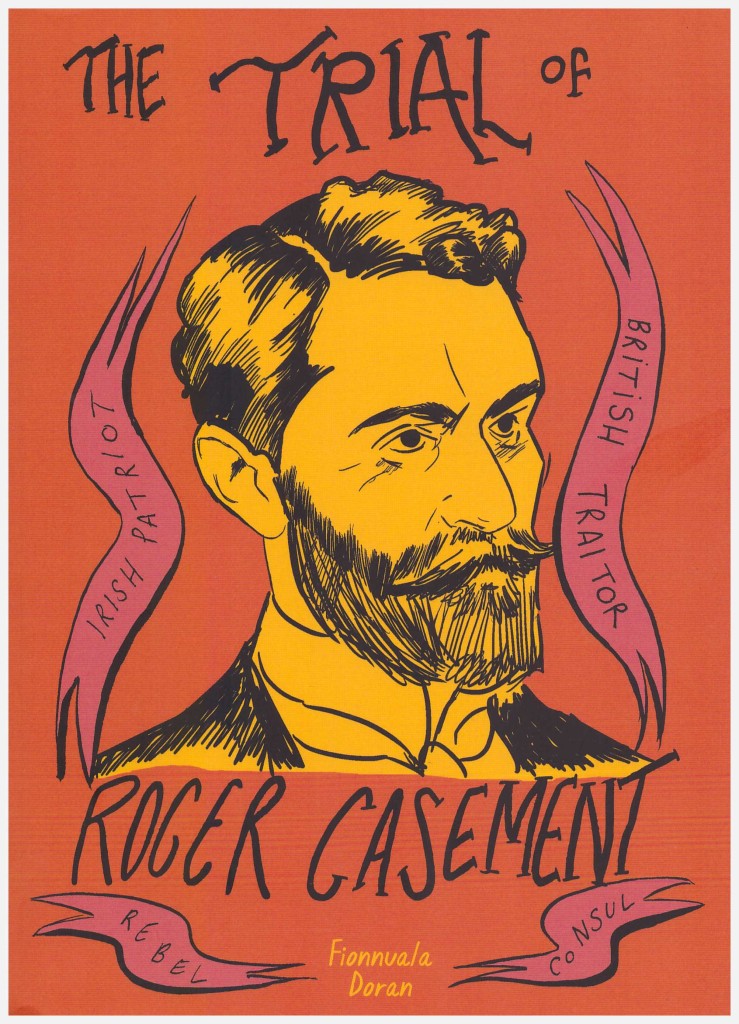

Martyr or traitor? On the centenary of his judgement Roger Casement is a man all-but forgotten in today’s Britain, yet in the midst of World War I his trial for treason was sensational and salacious. At least to those who knew the detail. The British establishment, fighting rebellion in Ireland, needed to make a very public declaration, and thoroughly discrediting Casement was the opportunity.

To all intents and purposes the Irish born Casement was an upstanding member of that establishment, knighted in 1910 for his diplomatic work in Africa where he was instrumental in highlighting abuses. Yet Casement was a deeply conflicted man, having to hide his homosexuality, still a criminal offence in his era, and gradually coming to believe extreme measures were required if Ireland were ever to be free of British control.

Promises of self-determination had been made by Prime Minister Asquith, which outraged Protestants in Ulster, and their opposition kicked plans into the long grass. It was under these conditions that Casement was seduced to the cause of the freedom fighters. As the British fought a war against Germany he agreed to visit that country with a dual mission. He was to persuade Germany to supply arms for the Irish fight, and to persuade captured soldiers from Irish regiments that their interests weren’t being met by serving in the British army. He rapidly and violently discovered his message was unwelcome to all but a very few.

Fionnuala Doran has some fascinating historical material to work with, including the possibility that Casement’s homosexuality was fabricated, but never entirely brings it to life. She chooses to cut and paste elements from Casement’s recent past between details of his arrest and trial, which confuses rather than enlightens as there’s no direct lead from one to the next. It comes across as random splicing when a chronological run through would have better served. Doran’s also opted for an understated and, as far as possible, strictly factual presentation, but choosing within this also to provide Casement’s narrative captions undermines a full understanding of a man who took an extraordinary journey. Until the final pages he lacks the stature of his position, and her loose version of Edwardian cartooning works for portraits, but also presents an exaggerated wild-eyed cast in moments of stress. There are further panels requiring considerable study to reveal their secret.

The most powerful sequence is a word for word presentation of the speech Casement gave to close his trial. It finally reveals the man in a coruscating condemnation of the laws under which he’s been tried and his assessment of Ireland’s plight. This though, is undermined by what’s in essence a good idea. Doran’s illustrations move through Ireland’s then present and future, counterpointed by Casement’s attempts to avoid his fate, and the destinies of some he associated with. There’s little context, however, and those unfamiliar with the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rebellion or the stature of John Galsworthy will be left none the wiser.

There’s no way of knowing the level of editorial input, but much of what fails to engage about The Trial of Roger Casement could have been relatively easily addressed, and that’s extremely frustrating.