Review by Ian Keogh

The Black Panther has been a troublesome character for Marvel over the years. Credit is certainly due for the introduction of a black superhero in the mid-1960s, even if the ruler of the technologically aware Wakandan nation in Africa hardly qualified as street even then. Beyond the introduction, though, Marvel experienced trouble in connecting the Black Panther with an audience, and while a frequently seen supporting character, sustaining his own series was always problematical.

Film director Reginald Hudlin’s interpretation of the character was a re-boot following the cancellation of the longest-lived Black Panther series to date eighteen months previously. After a promising start it lapsed into mediocrity, and much the same might be said of this series, although it began at a higher level and never plumbed the depths.

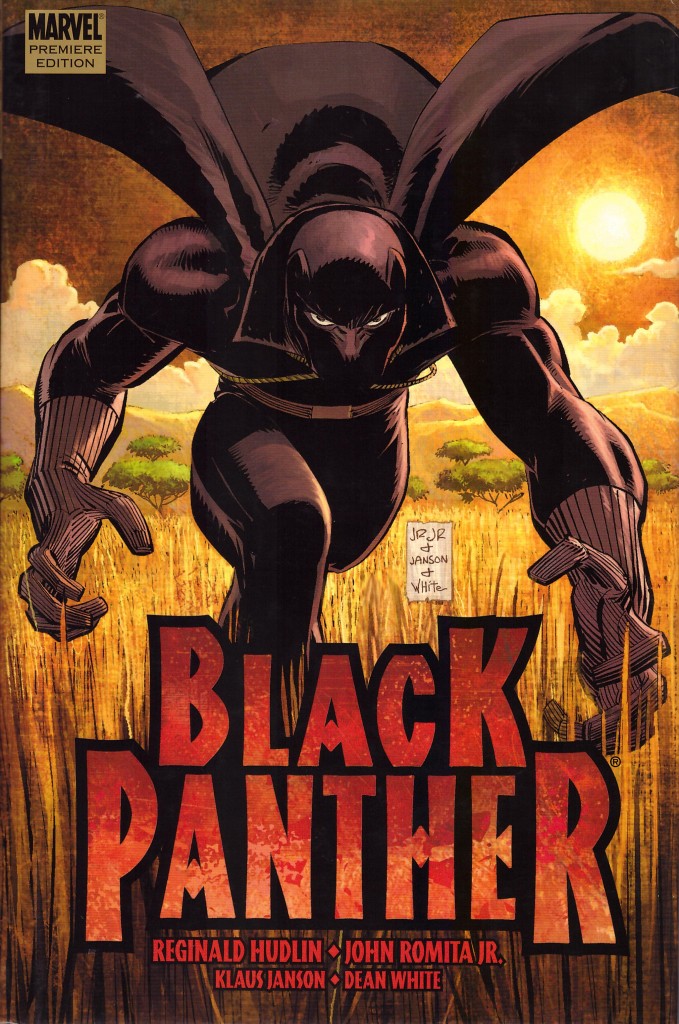

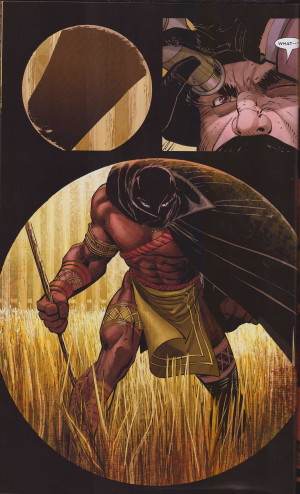

A big selling point is the art of John Romita Jr, at the time just developing the blocky and gritty style now associated with him. Romita Jr has been an accomplished layout artist able to emphasise drama almost since his earliest strips, but cuts loose here and delivers some great spreads and a powerful, yet athletic Black Panther.

Hudlin takes a leisurely approach to his storytelling, with the opening chapter a history lesson of Wakanda, against a background of envious American politics. He and Romita Jr show, in very impressive fashion, how the country has repelled invaders for centuries. It establishes the Black Panther as a hereditary position, yet open to challenge, and that when push came to shove, the Black Panther was able to see off Captain America. As opening statements go, it’s excellent.

From this point Hudlin’s approach was controversial on original publication. He refashions T’Challa’s origin, but does so very well, tinkering around the edges while maintaining the essence. This was still in the days before a reboot every three years did the same for other characters. The tale still involves Klaw, now with the US government to thank for his technological makeover, and adds several other stock super-villains, refashioning the Black Knight as a Vatican agent. T’Challa now also has a sister, and she’ll become increasingly important as the series progresses.

Hudlin makes the mistake of equating England with the United Kingdom, but otherwise doesn’t put a foot wrong here to the halfway point unless continuity is exceptionally important to you. From the halfway point, though, we move from the appetiser to the main course, and the content isn’t quite as impressive. The legend of Wakanda’s invincibility has been so emphasised that it’s difficult to believe a country that’s repelled all invaders for millennia can’t cope with Klaw, the Rhino, Batroc, Black Knight and the Radioactive Man. It’s here that Hudlin’s tinkering falls down. By all means re-work negligible villains, but isn’t it cheating to power them up to service the narrative convenience?

Everything looks great until the end, though, and the book really is worth getting for the opening chapter alone. Hudlin continues with Bad Mutha.