Review by Frank Plowright

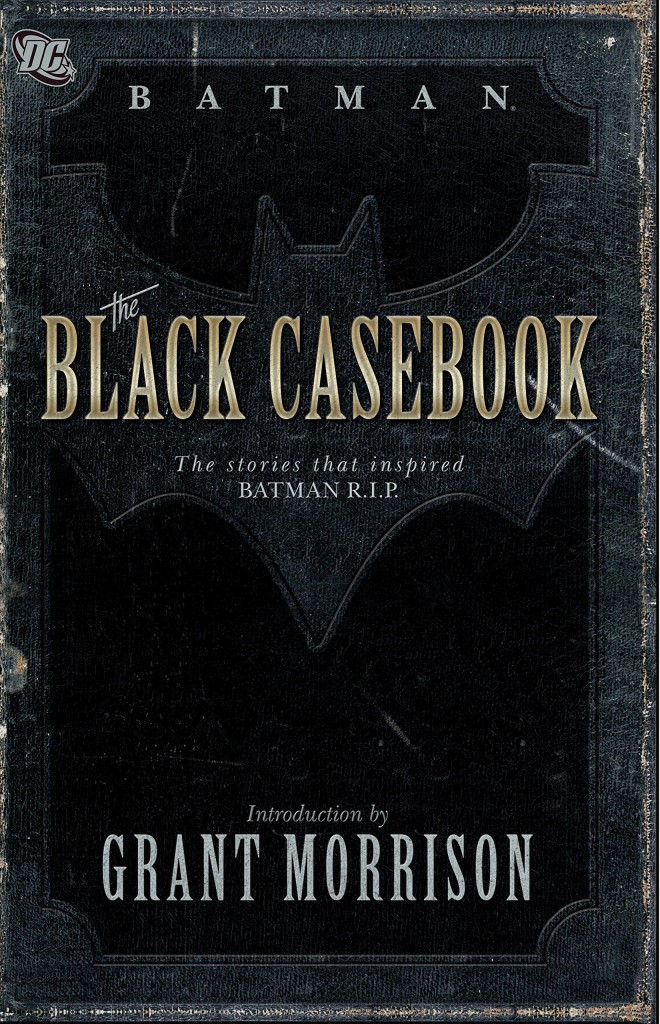

Certain types of examination demand notes in the margin, the display of workings, and in essence that’s what The Black Casebook is. It reprints 1950s and 1960s Batman stories that profoundly influenced Grant Morrison’s acclaimed run writing the character.

Before assuming control of the franchise Morrison diligently researched all previous Batman comics and conceived the ambition to integrate every version of Batman over the years within a single consistent character. Certain stories DC had long shuffled under the rug of embarrassment strongly influenced Morrison’s thoughts, and provided characters he revived and incorporated into his own myth-making.

The Black Casebook is a book Morrison referenced during his Batman, one into which Bruce Wayne noted the more inexplicable occurrences of his career. Morrison’s insightful introduction to these reprints notes how during his research he realised how universally applicable some of the story themes were. There’s a lack of sophistication in the execution, so upgrading was required, but he’s spot on.

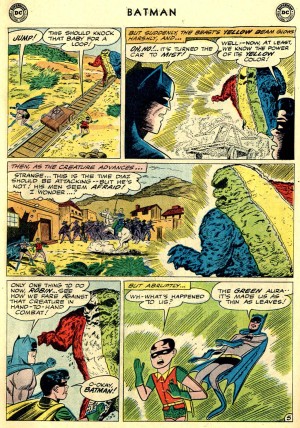

Batman and Robin meet British counterparts they’ve influenced, Knight and Squire, then the Batmen of all nations. They team with Superman, and more obscure heroes Lightning Man and Wingman, then learn how Thomas Wayne, Bruce’s father, was the first Batman. Batman meets Bat-Mite, and battles alien robots – or was that a dream? – develops a fear of bats, and declares his love for Batwoman. How will he squirm out of that one? Don’t get your hopes up!

Occasionally there’s a real surprise, a story that’s way better than expectation. One, by Bill Finger, has ‘Batman’ awakening, in costume, in a sanatorium where he’s been delivered by Batman. He knows he’s Batman and Bruce Wayne, but all evidence weighs against this, and encounters with Alfred and Dick Grayson reinforce that he’s delusional. In eight pages it cranks up the tension, and the denouement proved key to Morrison’s cohesion project. So is the tale in which Batman witnesses Robin’s death.

Most of the art is by Sheldon Moldoff, but in a style very much attributed to Dick Sprang (who also draws a couple of stories), cartoony and exaggerated with Batman caught at oddly stiff perma-grinning moments. It very much contributes to the off-kilter impression when viewed from a modern perspective. The writing, within the parameters, is surprisingly inventive, and mostly by Finger. Whether subconsciously or deliberately, Morrison has responded to just the material best calculated to thrill the young audience of the period. We have new heroes, toying with colour and costume variations, and fantastic situations. As even a cursory investigation of the period reveals, Morrison has chosen well.

If you’ve not read Morrison’s Batman run in its entirety some of its mysteries may be rendered impotent by his comments accompanying these reprints, so tread carefully. Those who have read it can be astonished at how faithful he is to the material here.

Morrison’s recontextualising, however, doesn’t rescue most of the material here from what it actually is. The 1950s and early 1960s were different times, and the Batman stories of the era reflect this. They’re resolutely optimistic, stomach-churningly chummy, and almost all devoid of any great logic even for superhero comics. Forget what Batman is today, though, discard that cynical 21st century veneer of sophistication, kick back and there’s a lot of fun to be had.