Review by Tony Keen

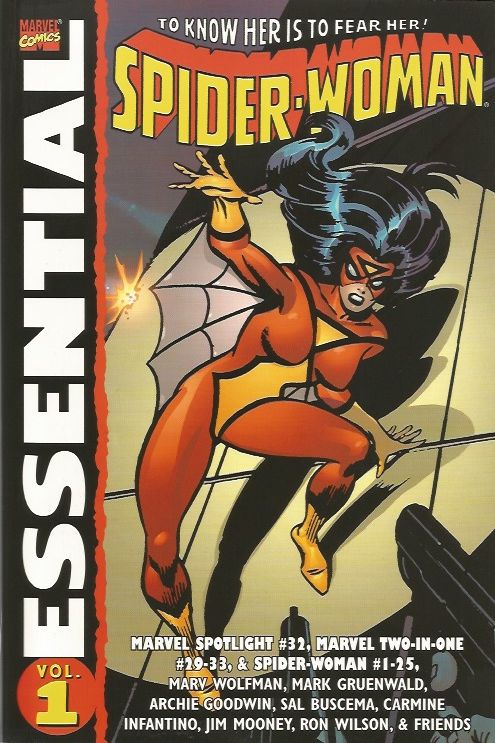

Spider-Woman was one of three heroines created by Marvel in the late 1970s primarily to establish copyright over female versions of their male heroes. Despite her somewhat inauspicious origins, Jessica Drew has gone on to acquire a considerable fanbase. On the basis of these stories, it’s hard to see quite how that came about.

Unlike Ms. Marvel and She-Hulk, who were both closely linked to their male equivalents, Spider-Woman had little in common with Spider-Man beyond the name and an arachnid basis for her powers – indeed, it was two years before the two met. In her 1977 origin, Archie Goodwin had Jessica Drew evolved from a spider, and placed in a competent spy story. Her look, designed by Marie Severin, owed little to Steve Ditko’s Spider-Man design, and was more reminiscent of DC’s mysterious superheroine Black Orchid, who had debuted a few years earlier.

High sales, probably because there were very few superheroines with their own series, earned a five-part story in the Thing’s team-up title, Marvel Two-in-One. It’s terrible, one of those 1970s US comics set in the UK where neither writer nor artist could be bothered to do any research, resulting in modern London being depicted as some bizarre mash-up of Mary Poppins and Curse of Frankenstein.

This blights the first few issues of Spider-Woman’s own title, launched in 1978, until she is relocated to Los Angeles, sensibly free of other superheroes, allowing her to make her own way, but also a locale the creators could convincingly portray. The series was written by Marv Wolfman, and drawn by Carmine Infantino, and attempted to blend superheroics and mystery, displayed by taglines such as “The Mysterious Spider-Woman” and “To Know Her is to Fear Her”. Wolfman created the villain Brother Grimm and reintroduced the Hangman from Werewolf By Night, but by his own admission never got a handle on the character. His replacement Mark Gruenwald continued the mystery angle more successfully, and one of his stories, ‘Eye of the Needle’, is the weirdest seen in the series, featuring a tormented villain who sews lips together. Gruenwald resolved the Brother Grimm plot, though along lines that were obvious from Wolfman’s lead-in, and had guest appearances from Werewolf by Night and the Shroud, but the stories remain pedestrian, and Infantino and then Gruenwald left after a year.

Michael Fleisher instigated the first of many “new directions” for Spider-Woman, instituting a career as a bounty hunter, and transforming the series into a more conventional superhero title, although without any discernible upswing in quality. A rotating series of artists had a tendency to draw close-ups of Spider-Woman while allowing captions and dialogue to describe off-screen action. At the end of the run covered here, Steve Leialoha arrived on pencils, having already inked others and produced covers – he would provide the title with much needed consistency in the art.

Throughout this collection casual sexism abounds, with plenty of leering comments about how good Spider-Woman looks in her tights, and an awful lot of dialogue taking place while Jessica is in the shower.

The volume includes text pieces on Jessica Drew and the Shroud, the first of which contains many spoilers for volume 2.