Review by Frank Plowright

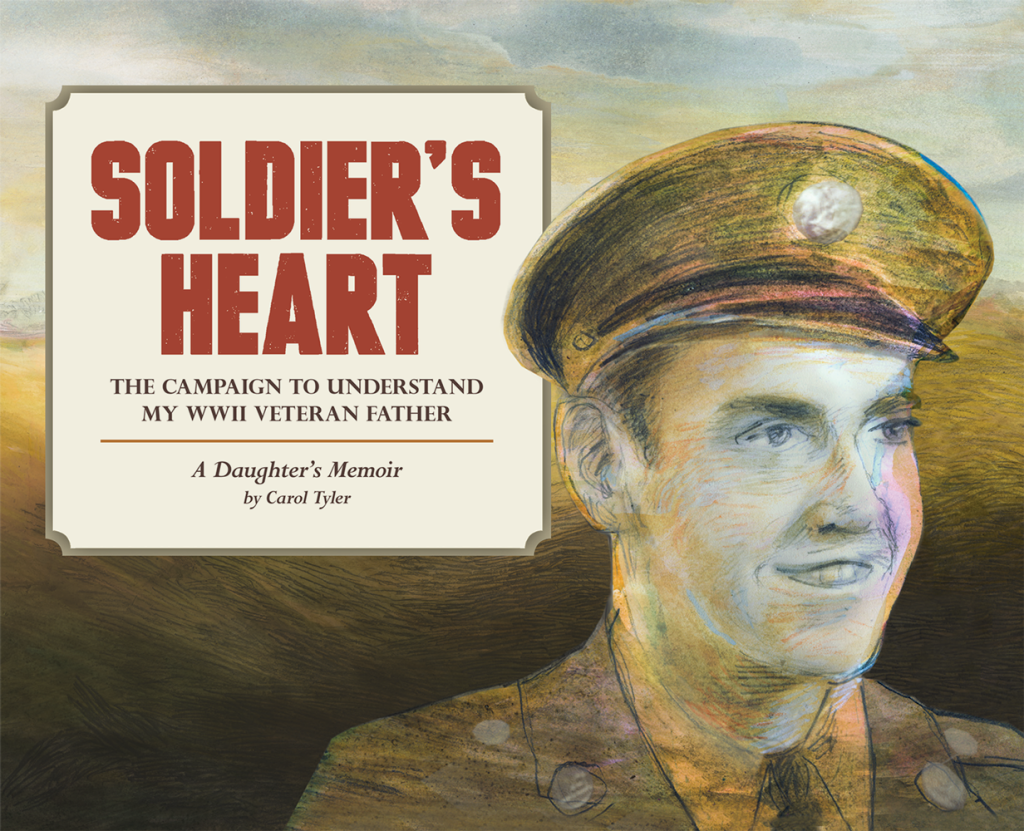

Soldier’s Heart is a touching, reflective and ambitious graphic novel that deserves a wider audience. It collects three oversize books originally published as You’ll Never Know.

Carol Tyler began this project by attempting to produce a form of illustrated scrap book adapting the notes and photographs her father Chuck took during his European service in World War II. As she was growing up in the 1950s and 1960s this was always a no go area, enquiries fobbed off with a dismissive comment, so it was astonishing to Carol that in 2001 her father phoned in order to speak for two hours on the topic. There was a purpose behind his sudden lack of reticence, but that’s only disclosed relatively late in the proceedings.

Were that the only strand presented here, the graphic novel would have great merit, but there’s so much more. Tyler was experiencing personal problems at the time, and these and the subsequent troubles for her daughter are poured in, as are her mother’s recollections, including a deep family secret never really aired or properly dealt with.

With all this material Tyler retains her original scrapbook method, leading to wildly disparate forms of storytelling. When traditional forms don’t work the way she wants, she adapts by creating a new narrative method, maybe using a map, or in the case of three people simultaneously talking over each other, interweaving strands of ticker-tape dialogue in identifying colours. Her father’s recollections are presented as small illustrations accompanied by text, and numbered as if a trading card series, she spins in symbolism, and supplies lovely watercolour paintings. These constantly adaptive methods form a stunning visual collage, and if Tyler’s cartooning appears simple and sketchy at times, that’s deceptive. It’s a style well up to everything she wants to convey, and also serves to distance from some pretty upsetting events.

There is a gap in Chuck’s memories. He knows he was shipped back to the USA after being injured, and recalls the circumstances of the injury, but can’t bring the interim to mind. Filling the gap becomes an almost mythical quest, involving missing records in offices staffed by inefficient automatons, who nonetheless must stick to rules. Never mind that people have driven several hundred miles to visit, and the mistake is not theirs. It’s no great spoiler to reveal that answers are found, they’re suitably distressing, and there’s a monumental, but genuine, underlining of the moment by nature.

The subtitle of The Campaign to Understand my WWII Veteran Father sums up another narrative strand. Chuck is a grouchy man, contradictory, but with a high work ethic, never considering he’s contributing unless there’s a tool in his hand; the type of man who’ll uproot to the wilds of New York state in his seventies to build a new home. What shaped this man is gradually unwoven through Tyler herself having to come to several traumatic re-adjustments to her life.

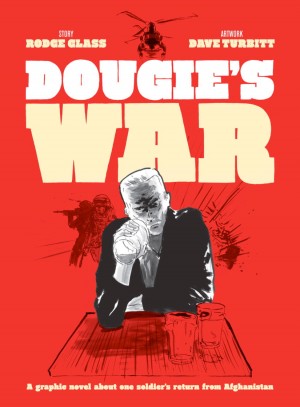

Illness stalks several people throughout the book, and the title is a term that can be tracked back to the mid-19th century as applied to what we’d now call post-traumatic stress. It’s generally a diagnosis connected with a specific event, but could equally apply to several unravelled in Soldier’s Heart.

This is a work that withstands comparison with any book considered among the upper echelon of graphic novels. It has vast emotional depth, several compelling narratives, displays innovative techniques, is visually stimulating and yet never strays from accessibility.