Review by Frank Plowright

Gantz started off very strongly with the premise of those on the verge of death able to prolong their lives by killing aliens in designated arenas. It then hit a bit of a slump as Hiroya Oku prolonged his scenes far longer than necessary via repetition. There were, however, the grass shoots of a revival in Gantz Omnibus/3, and that promise is fulfilled here in what’s the best series Omnibus to date.

It breaks down into three separate components, although not quite as conveniently as one occupying each of the three larger sized paperbacks combined here. The content of what was Gantz/10 definitively introduces a few new characters who’re exceptionally talented in the real world, spending some time with them and their motivations. Cleverly, though, by the final pages we’re not sure how much of the previous events have just been main character Kei’s dream. Although a hoary old narrative cliché, Oku plays it well.

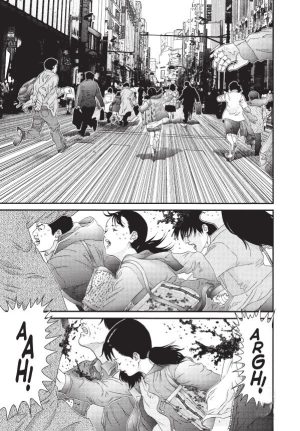

The following section was largely contained within Gantz/11, and spends an agonising amount of pages detailing a massacre in a busy district of Tokyo. If the event itself wasn’t shocking enough, there’s the added tension of Kei’s girlfriend being in the area and his being unable to reach her. The new characters previously introduced have a part to play. A theme throughout has been Izumi, a fellow pupil at Kei’s school, wanting to head back to the Gantz arena, and that duly occurs in what was Gantz/12.

In a series characterised by excellent art, this is hits the highest standards to date. Telling three very different types of stories, Oku brings the necessary weight to all of them. The character-based opening section drips with emotion, while the level of detail to the location and the amount of people involved in the massacre is astounding. The final section is combatants facing dinosaurs, and Oku’s obviously having a ball drawing those. The quality continues in Gantz Omnibus/5.

The one stain on an otherwise excellent volume is Oku continuing to separate his chapters with illustrations of half-naked women. They’re offensive objectification, out of place, and draw attention to how shallow the characterisation of women within the main story is.