Review by Win Wiacek

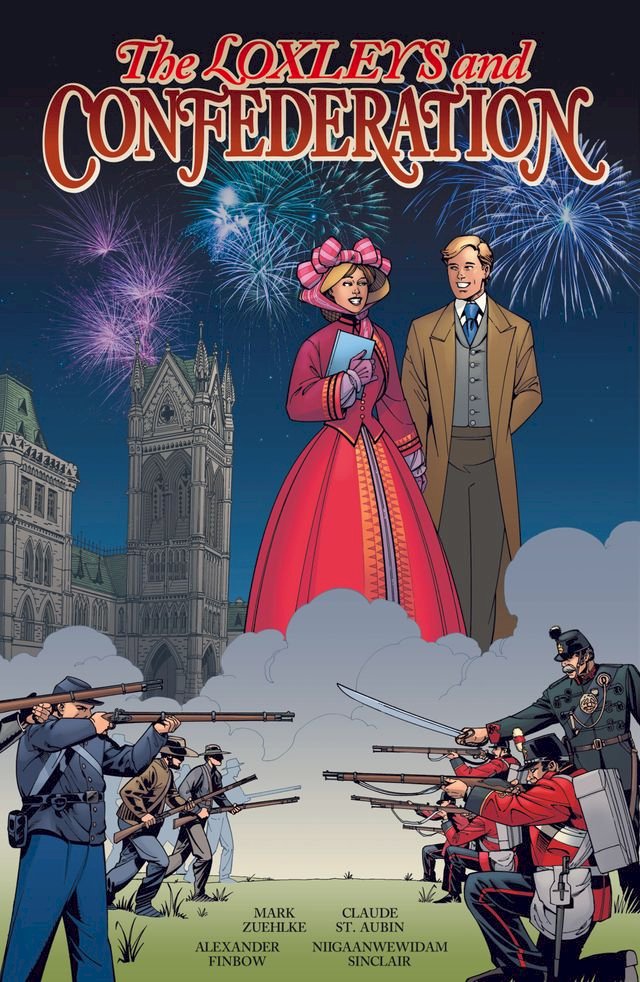

The Dominion of Canada officially came into existence on July 1st 1867. Inspired by the 150th anniversary, Mark Zuehlke and Claude St Aubin revisit how that happy circumstance came to be via a splendid full-colour hardback graphic novel.

This follows the same family introduced in The Loxleys and the War of 1812, examining the facts of the clash through the eyes and experiences of one extended family caught up in the conflict. This sequel recaps the fateful first European incursion into the vast northern regions, the (mostly) shameful interactions with the native peoples there and the complex, dramatic campaign resulting in a disparate aggregation of fiercely independent colonies finally accepting they are stronger together.

Canadian military historian Zuehlke includes contributions from Alexander Finbow and scholar, commentator, author, and advocate on indigenous issues Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair, and this compulsively engaging story is illustrated with captivating veracity by Claude St. Aubin.

The show begins with a prologue set in 1534 when French explorer Jacques Cartier sails up what will be later be called the St. Lawrence River. Sadly the ‘civilised’ trailblazer then acts rather rudely towards the natives he meets. Despite an inauspicious start, grudging trades are made but when Cartier finally leaves he takes with him the two sons of local chief Donnacona. The Frenchman still wants treasure and insistently urges the native boys to direct him to a priceless valuable they call “Kanata”.

Skipping ahead to 1864 we find the Loxley clan has grown in numbers, prosperity and influence. It is August 1st and 13-year old Lillian is recording in her journal the event of the family’s first great gathering in years. Amidst the usual chatter of ageing, absences and ailments, the elders are preoccupied with a thorny political problem. The United States has been at war with itself for four years but that struggle is almost over and the local consensus is that many Yankee warhawks are eager to continue fighting. They justify it via their deplorable political tenet of “Manifest Destiny” to conquer and possess the entire continent, not only from East to West but also from South to North.

Talk of Confederation of loosely aligned Canadian states makes little headway until a US invasion is again a serious prospect. Politicians begin actually talking to each other and making progress.

The prospect is of particular interest to Lillian, subsequently invited to accompany her illustrator mother and journalist grandfather as they journey all over and around the scattered colonies and even to England itself. The debates perpetually appear to take one step forward and two back as regional issues and grudges always hold back the urgent drive to combine, even as the outer world constantly impinges on what might seem to be a strictly colonial issue.

Thus unfolds a compelling history lesson couched in absorbing human terms and rendered totally irresistible for being seen through the lens of an idealistic child’s eyes: a girl becoming a woman whilst her little bailiwick becomes a mighty nation.

Also woven into the tale – thanks to the input of Sinclair – is a telling examination and assessment of the shameful official policy of assimilation legitimising maltreatment of indigenous people throughout Canada’s history.

Informative, engaging, even-handed and intensely gripping, this account of ordinary people at the core of grand historical accomplishments is an astonishingly readable chronicle.