Review by Win Wiacek

We tend to think of graphic novels as being a late 20th century phenomenon, and one that fought long and hard for legitimacy and a sense of worth, but the format was pioneered and popularised much earlier in the century, and utilised for the most solemn, serious and worthy purposes.

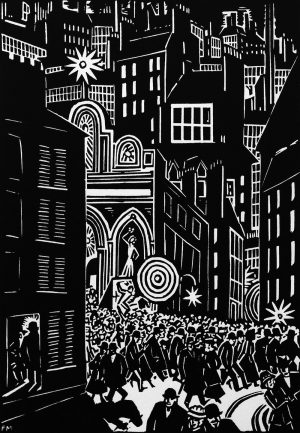

As the earliest newspaper strips were being rebound as collected editions, European fine artists were addressing the world’s problems in “Wordless Novels”. They assembled individual artworks – usually lino or sometimes woodcuts – into narrative sequences, which as the name implies, used images, not dialogue or captions, to tell a story.

They were most popular during the 1920s and 1930s, and undisputed master of the form is Flemish artisan Frans Masereel, whose many works were phenomenally popular in German and whose influence spread far and wide. In Depression-era America Lynd Ward adopted the process for his many sallies against social iniquity, and Giacomo Patri unleashed his anti-capitalist salvo in the wordless novel White Collar as well as comedic parodies such as Milt Gross’ He Done Her Wrong.

Avowed pacifist Masereel created his first narrative in 1918 with 25 Images of a Man’s Passion and followed up a year later with his masterpiece Passionate Journey. He eventually crafted over forty wordless novels, primarily woodcuts, but also a quartet of traditional pen and brush sagas. Always stridently and forcefully defending the ordinary man from the horrors of capitalism, disaster and especially warmongering, his potent ability to hone meaning and capture emotion in singular images influenced generations of artists and cartoonists.

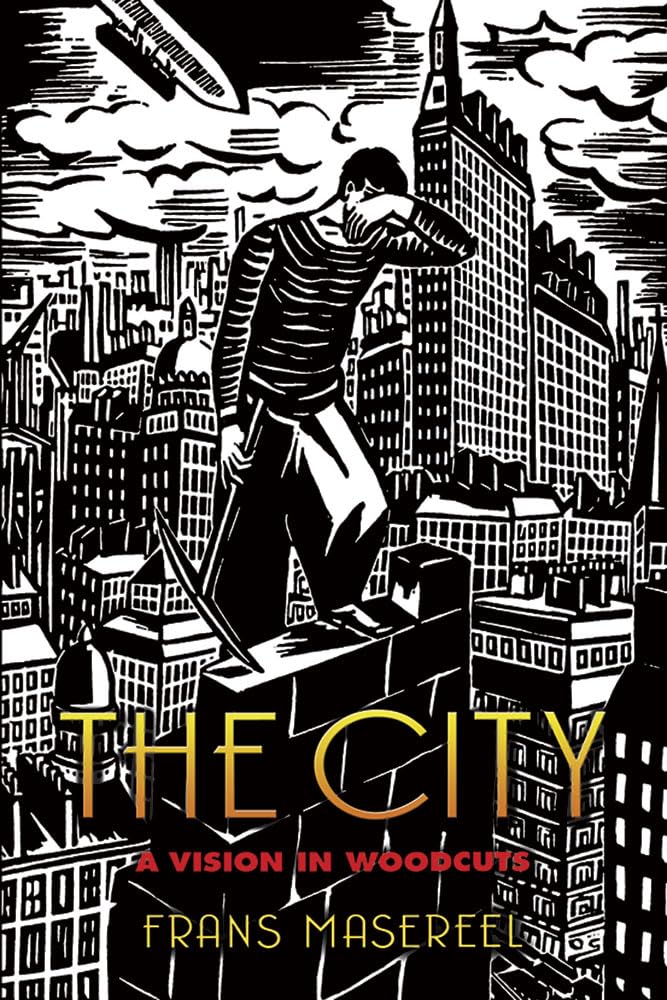

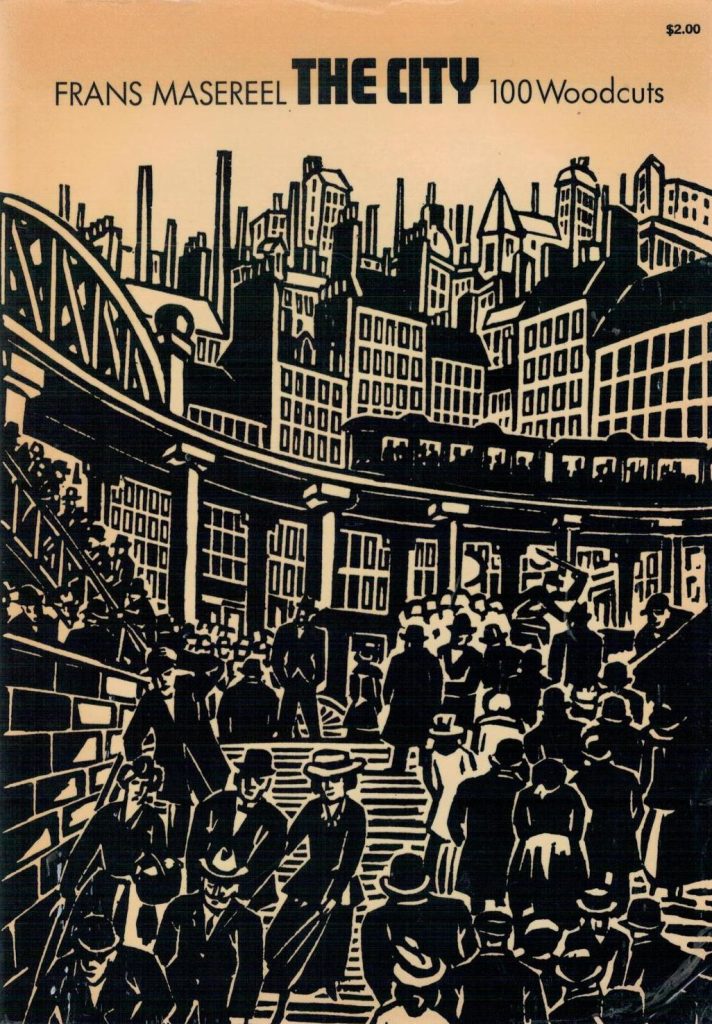

The City was first released in 1925 as La Ville: cent bois gravés in France and as Die Stadt in Germany. Originally comprising 100 prints (13cm x 8cm) bound into book form, it quickly became a touchstone for many artists and critics and was hailed as the precursor of a film genre which made environment the focus of narrative and subsequently reissued in 1961, 1972 and 1988 before this definitive 21st century Dover edition.

The City: A Vision in Woodcuts is translated from the German version as produced by Kurt Wolff Verlag AG (Munich 1925): seeking to forego actual sequential narrative by delivering its stark and startling images encapsulating the modern urban existence. Of course, humans being what we are, readers will find themselves unconsciously imposing form on those unfolding, uncompromising extremely explicit images anyway.

The highest and lowest echelons of society rub up against each other, zeroing in on the emotions, reactions and consequent horrors such friction creates. There are bawdy entertainments, diligent toil, crimes of all kinds, quiet times almost unnoticed. We see tall smoking chimneys, railway lines, canals, ports, traffic jams, subways and stations. There are rush hour crowds, fights, civil protests and always personal tragedies: accidents, bad births, thefts, affray, rape and murder.

Buildings go up and come down, there is rush and rubbish and courtroom drama, vast office regiments, factory lines and foundry creations. Opulence and desperate poverty co-exist, with the exploited, maimed, forgotten and unwanted ignored by those enjoying themselves at all costs. The masses sing, dance, drink carouse and even indulge themselves being part of a grand state funeral. Always people come and people go, some for a different life and others to a “better world”.

It’s a place of constant change and the pace never slows. Stirring, evocative and still movingly inspirational this magnificent rediscovery is inventive, ferocious in its dramatic delivery. It’s instantly engaging and enraging: a book long overdue for revival and reassessment and one every callous “I’m All Right” Jackass and “Why Should I Pay For Your…” social misanthrope needs to see or be slapped with.